In many an industry, the idiom “how the sausage gets made” connotes pulling away the facade of something to discover the unpleasant, even nasty process behind it. But Carolien Niebling—a 33-year-old designer based in Lausanne, Switzerland, who spent the past three years researching, writing, and editing a book on the very subject of sausage-making—has a different take, at least when it comes to the food item itself. For The Sausage of the Future, just out from Lars Müller Publishers, Niebling collaborated with a master butcher, a chef, three photographers, and a graphic designer, all while she was a part-time assistant in the master’s product design program at ECAL, to create a compelling exploration of sausage as a design object. Delving into production techniques and potential new ingredients, the book may be the most transparent look at, as Niebling herself describes it, “one of mankind’s greatest edible inventions.” Here, a selection of images from the book, as well as an edited interview with the author about the undertaking and why sausage has remained such an enduring favorite.

How the Sausage Is Made, Literally

In her new book "The Sausage of the Future," Carolien Niebling dissects the tubular meat—and it's beautiful.

In her new book "The Sausage of the Future," Carolien Niebling dissects the tubular meat—and it's beautiful.

As a product designer, I’m fascinated with food. I think there’s still so much more for designers to do in the food industry—the same types of production methods have long been in place, and there are few designers working in the field today. This is why I want to explore this sector further.

Around three years ago, I became fascinated with the massive amount of meat humans eat. I began thinking, Well, what’s the industry doing to address this consumption? I found that most of the solutions were being worked on were based on faking meat or replicating it—with the same texture, flavor, and appearance—via stem cells in a laboratory. I found both of these solutions overwrought. They tell the consumer the wrong message, because if you fake something, the consumer thinks, Okay, then we can continue to consume the way we have been for ages.

I thought it would be interesting to look at sausage for this reason. The sausage is one of our oldest designed food items—it was invented about around 5,000 years ago. Back then, of course, making sausage was very logical: Meat is a protein power plant, and we needed to use everything we could in the animal for sustenance. What I find so impressive is that, because of this long history of development, we managed to learn how to preserve a raw piece of pork with a thin casing, without refrigeration. That’s actually incredible!

This book project completely changed my outlook about sausage. If you ask somebody about sausage, they often arrive at a memory. And the memories are often very positive: They’re barbecuing at the lake, or they’re camping with their kids. I now believe that, if we can use old food bits that we would normally really not eat, like ears or eyes, and they taste good, why shouldn’t we? If you judge it only on the flavor, there’s nothing to argue about. Sausage is a crowd-pleaser.

I don’t like processed foods at all. So, for the book, I worked with a very good butcher, Herman ter Weele, in the town of Oene, in The Netherlands—close to the village where I grew up. Every sausage we used was very well made. I also bought practically every type of sausage I could find and did a lot of research. I really think that there’s something to admire in using leftover or scrap bits to make something so delicious. You can barely overcook a sausage. It’s always juicy, often salty and flavorful. It’s a very forgiving food.

What surprised me about this project was learning more about the design of sausage, how the glue works—I had never thought about it. The book was really about trying to find out what holds a sausage together. It’s a simple science that everybody can understand—or at least that’s how I tried to write it. I started to look into hydrocolloids, which are widely used to improve quality and shelf-life. At first, you think, Ahhh, I don’t know these technical words! But it’s really not that complicated.

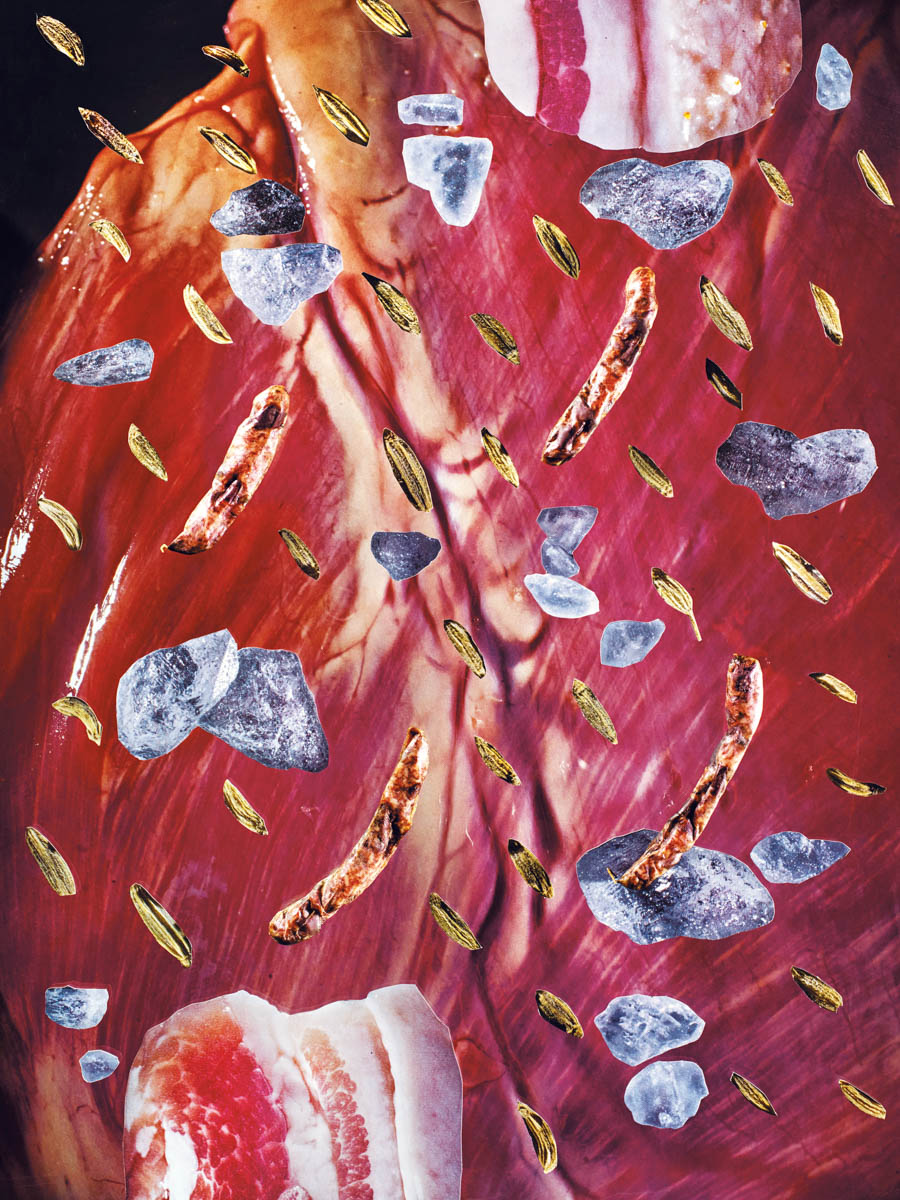

What I really wanted with this book was something visual—nowadays, we don’t read so much anymore. I wanted to give information, but I also wanted people to become interested in the subject just by looking at it. For this reason, the book begins with these colorful collages of the ingredients. With the photographer Emile Barret, we pulled out all the key ingredients inside the sausage and photographed them with a microscopic camera. Then we cut them out and laid them around the sausage. Each is a real photo, not Photoshopped or anything. For another series of images in the book, I asked the photographer Jonas Marguet to help me portray the sausage in the form of characters: a manly, robust sausage, say, or smart, delicate, softer sausage.

For the other series of images, these black-and-white photos by Emile Barret and Noortje Knulst, we wanted to show process shots. These were taken during visits to the butcher on two occasions, during which we were testing different types of sausages. Working with this butcher was a turning point. He’s a very inspirational guy. He also hunts, and argues, “I cannot be a butcher without being a hunter, because nature is a very important resource and a place where we should get our food from.” I totally agree. There’s no more happy life than that of a deer that was born and bred in the forest. This butcher controls everything himself; none of his meat comes from abroad. If we eat meat, he and I both think it should be this type.

I also worked with a chef, Gabriel Serero, who specializes in molecular gastronomy and food textures. With all the textures he creates, eating stays interesting. For example, using fibers in the insect flour that were quite difficult to work with, we eventually made a good recipe in which the fibers dissolve, with a smooth, good-tasting result.

I think what designers can do in the food industry is to look at opportunities for tweaking existing production methods, optimizing or changing them. My thought is, If there’s a new food to be produced or introduced to the market, why should we then also make new machines for it?

What’s really important in this project is all the different fields in it working together: food and graphic design and photography and writing. For me, it was a first—I’d never done a book before. I went into the project rather naïve, and I gave myself enough time to research properly. When I started, I’d just graduated from college and had a part-time job. I had the time to go in and dive deep. What I’ve realized most is how much there still is to do in terms of food and design. There’s a Grand Canyon of possibilities.

(Opening photo: Emile Barret)