In this column, we ask our special projects editor, Bettina Korek, founder of the Los Angeles–based independent arts organization For Your Art, to select something in the world that she believes you should be aware of at this particular moment.

Agent Provocateur

Literary agent John Brockman flouts the boundaries between art and science.

BY BETTINA KOREKPORTRAIT BY OGATA November 10, 2016

One day in 1964, John Brockman went on a stroll through Central Park. He was working as a banker at the time, and wore Brooks Brothers suits almost daily, but he had brought his banjo with him on his walk. Avant-garde artist Jonas Mekas happened to be filming there with his 8 mm camera, and turned his lens on Brockman and the incongruous instrument. The two spoke, and the chance encounter helped send Brockman down a winding, lifelong path through the intersections of science and art.

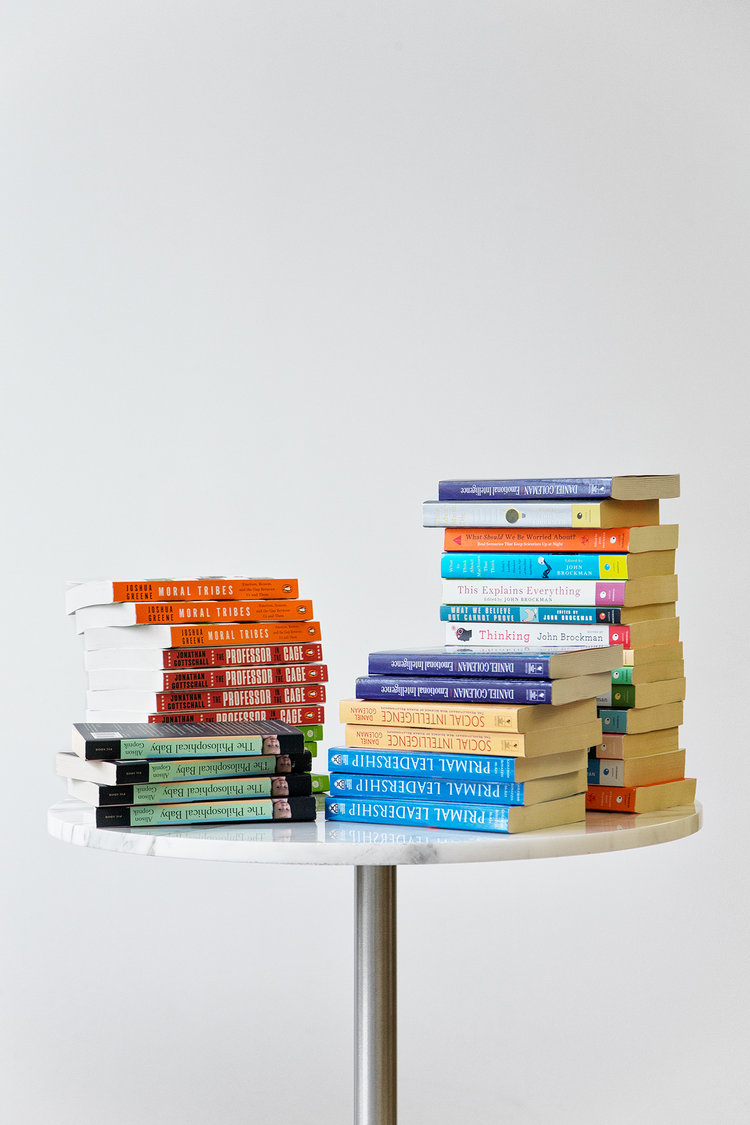

Best known as a literary agent, Brockman’s career has spanned art, science, film, theater, and digital media. For more than 50 years, he has served as a steady intermediary between disciplines, working with everyone from Stewart Brand, creator of The Whole Earth Catalog, to curator Hans Ulrich Obrist. He specializes in science literature and represents a roster of authors—including Jared Diamond and Steven Pinker—who are more widely known than he is. But Brockman’s preference has always been for the perimeter. He founded edge.org, a foundation with the mission of connecting people “working at the edge” of a wide range of disciplines. In his own writing, he advocates for a “third culture,” a synthesis of science and the humanities, with no smaller a goal than “rendering visible the deeper meanings of our lives and redefining who we are.”

Before he met Mekas, Brockman had moved to New York to start an investment banking company. Yet he had always wanted to be involved in the arts, so when he found out that a friend from childhood was involved with the experimental theater and poetry center, Theater Genesis, in the East Village, he saw an opportunity. After all, this was “the dead center of the most interesting culture of New York at that time, where anyone with a hip sensibility was going to poetry readings,” he says. Always clad in a suit, Brockman often broke down chairs and cleaned the floor. “Everyone at Theater Genesis was working at other places to support their aspirations. Many went on to do great things,” including the celebrated playwright, actor, and director Sam Shepard.

After a few months, Brockman proposed a film program at the theater. With the green-light from its founder, Ralph Cook, dozens of filmmakers showed their work at the first screening. It felt more “open-ended and accessible,” says Brockman, than the program at another avant-garde bastion: the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque, run by Mekas.

Meanwhile, Mekas had conceived a new film festival, called New Cinema 1, which enlisted dozens of visual artists to present a work somehow involved with film. Impressed by Brockman’s production, Mekas invited him to run both the Cinematheque and the festival while he traveled to Latvia for six months. Brockman closed his Park Avenue office and, armed with Mekas’s artist list and the Cinematheque’s checkbook, left his finance career for good.

The result took the creative world by storm. The series, still considered a watershed art-historical moment, culminated in a packed evening with the likes of Robert Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenberg, and others at the crossroads of art and science in attendance. “Everyone was reading [Marshall] McLuhan and [Norbert Weiner’s] Cybernetics at the time,” says Brockman. “There was a sense that something new was happening—nonlinear relationships between input and output, the viewer as part of the piece. New forms were all informed by scientific ideas.”

Brockman’s world expanded exponentially from there, including visits to Brand to help edit Brand’s groundbreaking Catalog. He traded book recommendations with Rauschenberg and John Cage (the former was taken with James Jeans’s The Mysterious Universe; the latter gave Brockman his copy of Weiner’s book), and he embarked on his career-long mission to shape the future by continuing to foster similar connections. “I have three friends: confusion, contradiction, and awkwardness,” Brockman says. “That’s how I try to meander through life. Make it strange.”