To fully appreciate Future Sex (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), Emily Witt’s Tocqueville-esque exploration of contemporary mating habits, it’s important to look back. My own introspection took me to a time just before puberty, when I had, without warning, become a walking Playboy cartoon—a frothing cliché. All of my friends had, too. Sex was suddenly on the mind all the time, even though we didn’t exactly know what it was. The basic rudiment was easy enough to grasp: women looked beautiful naked.

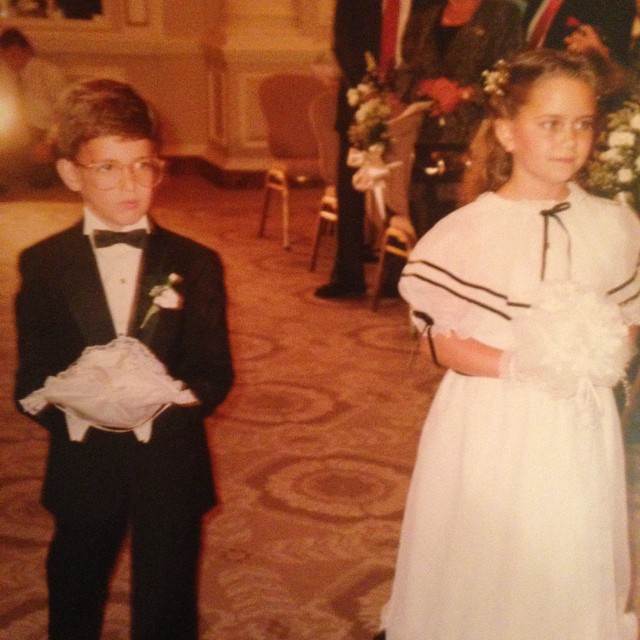

It was New York City in the mid-’90s, and we were attending a school for boys on the Upper East Side. Our doodles had turned from smiling suns and stick figures to breasts and little else; daydreams moved from the Batmobile to sandy beaches where Cindy Crawford and Elle McPherson lay naked. There was no interaction, just a silent invitation to ogle.

With no girls around, our inspiration had to come from elsewhere. Public access television—“Channel 35,” as we referred to it—was a great source thanks to Robin Byrd, a former porn star whose eponymous late-night show presented dancing strippers. Nudity taught us something about attraction, but it was another, subsequent discovery that would unlock a vault of information.

My friend Will had found a VHS cassette hidden in his father’s desk called The Party. It was full-length blue movie about what the title suggests, but that’s not all it was. For me and the other boys who’d beg for a sleepover at Will’s house, it was our sexual Rosetta Stone. The answers came at once. It was all downhill from there.

Saying the lustful generations of the today have it easier is an understatement. VHS is obsolete and print magazines are scarce. The Party, in that sense, is over.

I don’t remember ever thinking that one day I’d find a paramour (one night, maybe two) or a partner (ostensibly, more times than that) by answering personal ads or scrawling sonnets on parchment by candlelight. But as I came of age, the endeavor became less a hunt and more a game of bobbing for apples. All this entirely due to the digital revolution.

Enter Emily Witt, a chronicler of contemporary prurience, who, with her debut Future Sex, has created not only a roadmap of where we’ve come, but also a mirror of the times. The book has a lot in common, as has been pointed out in several other reviews, with Gay Talese’s 1981 book Thy Neighbor’s Wife, which examined similar themes during the Post-War period. Witt, like Talese, descends into a world of otherness, writing soberly, with a clinical, journalistic tone, even when walking the reader through topics such as polyamory, internet pornography, and webcam sex.

She tastefully describes even the most indigestible scenarios, like the scene during a webcam sex session with star Elisa Death on a website called Chaturbate: “I looked in at midnight and the camera was trained on an empty bed. Even empty, her room held the number-three spot on the website. Twelve hour later, I looked again. For more than 1,700 viewers she sat on the floor naked next to a pair of ballet slippers with an unlit cigarette in her hand. Some of her chatters wanted more sex. Most of them didn’t care.” Hers is a prose of dilution—in that whatever primal response that Death’s audience may have experienced is lost in translation.

But at times, reading Future Sex, I’m at a loss. Most of the book is an examination of obscure subcultures. There is a feeling that Witt strapped on a safari helmet before setting off on her reports. I was no stranger to online dating, which was always a great vehicle for staving off meltdowns after a breakup. But Chaturbate, for instance, left me jarred, even as a 30-year-old straight man working in media. It’s a niche product that’s alien to me—but on the other hand, that’s the point of Witt’s book.

Sexuality can no longer be bifurcated into deviant and non-deviant, good and bad, black and white. We’ve come a long way from the prescriptions of Robyn Bird and the tapes found in our parents’ drawers. We want more than that.

___________________________________________________________________

A version of this article appears in the forthcoming spring/summer 2017 issue of Centre, a semiannual magazine produced by Surface Studios.