Long before she had access to a computer, Vera Molnár was already thinking like one. To create her geometric images in the 1950s, she invented a systematic procedure: a series of exploratory steps and rules that aped a computer’s inputs and outputs, and dictated the final, hand-drawn form of her work. Dubbed “machine imaginaire,” her process was as much a tool as it was a concept with which to reprogram traditional visual practices. It was a radical adoption of technology—however much imagined—that would blaze a trail for computational art and design in the decades to come.

Working at a time before new media was widely embraced, Molnár’s canvases have largely been forgotten—that is, until now. The pioneering contributions from this 90-year-old artist, who is still working today, will be celebrated this November at the Museum of Modern Art’s new exhibition, “Thinking Machines: Art and Design in the Computer Age,” open today. Examining how art and technology interacted between 1959 and 1989, when personal computers were just arriving on the mass market, the exhibition (which will also highlight artists Waldemar Cordeiro, Lee Friedlander, and Alison Knowles) turns the spotlight on Molnár’s inventive use of machines, and her overall impact on the field.

“Because of her conceptual approach to computing, Molnár’s work is an important part of this exhibition’s thesis: that the computer and its attendant logic were used by artists and designers even when they weren’t working directly with those tools,” explain the exhibition’s curators, Sean Anderson and Giampaolo Bianconi. “What viewers are seeing is the simultaneity of a rigorous process as well as the work itself. Read as transparencies, the process and conceptual meet.”

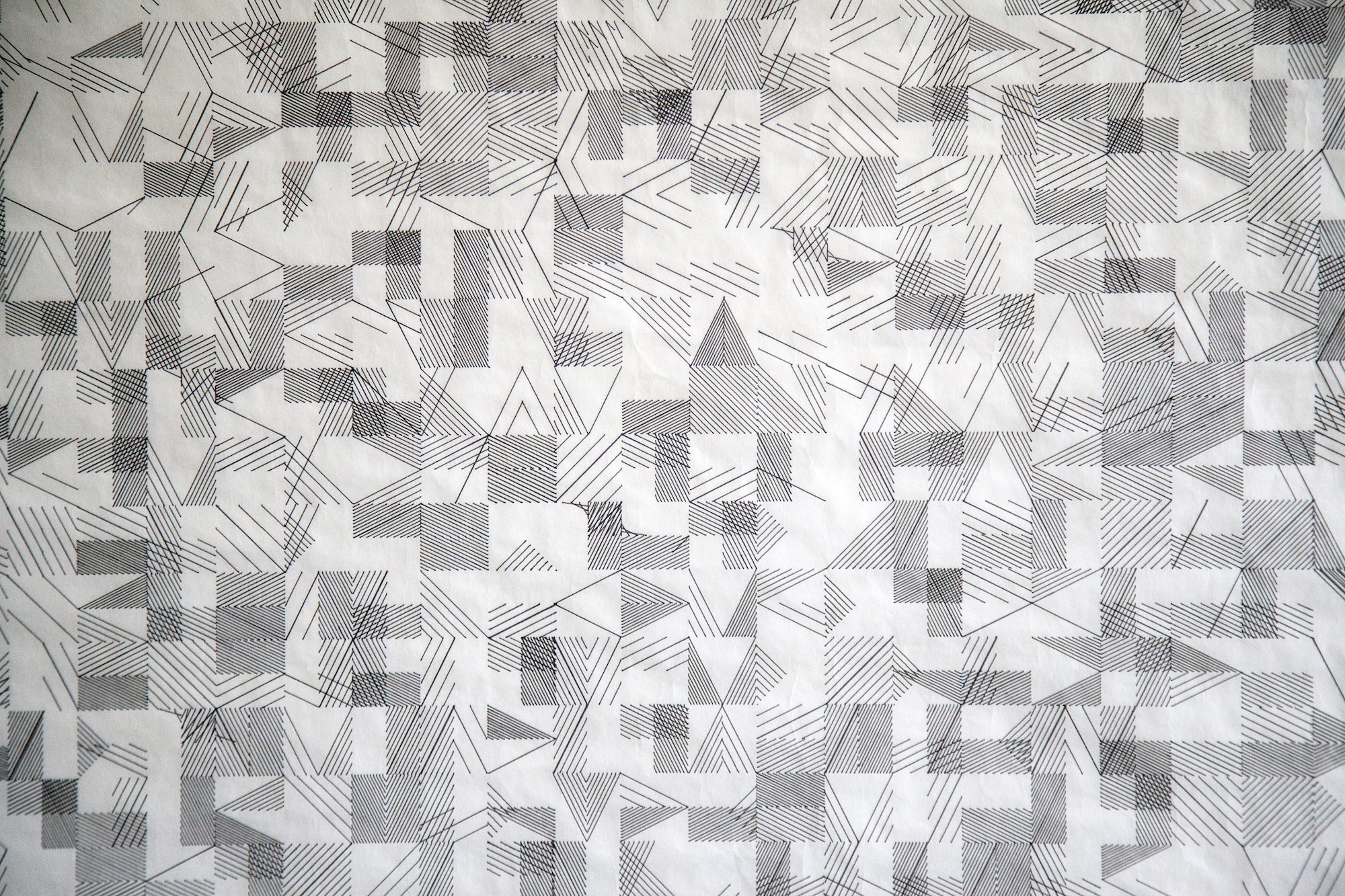

From 1968, the Hungarian-born Molnár transitioned from thinking like a machine to actually working with them, incorporating a computer and plotter into her process. With these new tools, her images bloomed with complexity. The minimalist logic of her 1957 “Slow Movement” series would evolve into the intricate matrix of “Square Structures” in the ’80s, demonstrating her commitment not just to geometry and sequential thinking, but also to enhancing her practice with technology.