I probably started to think about the relationship between buildings and music even before I was conscious of it. As a child, you echolocate spaces—my 6-year-old son will make particular sounds, just to play with a space and find himself within it. I used to do that, too. Later on, when I started making music, I would go into different spaces, like a concert hall or a church, and play one note for hours. I was fascinated by the idea of sympathetic resonance, of finding a corner in the rafters that resonates with a particular note.

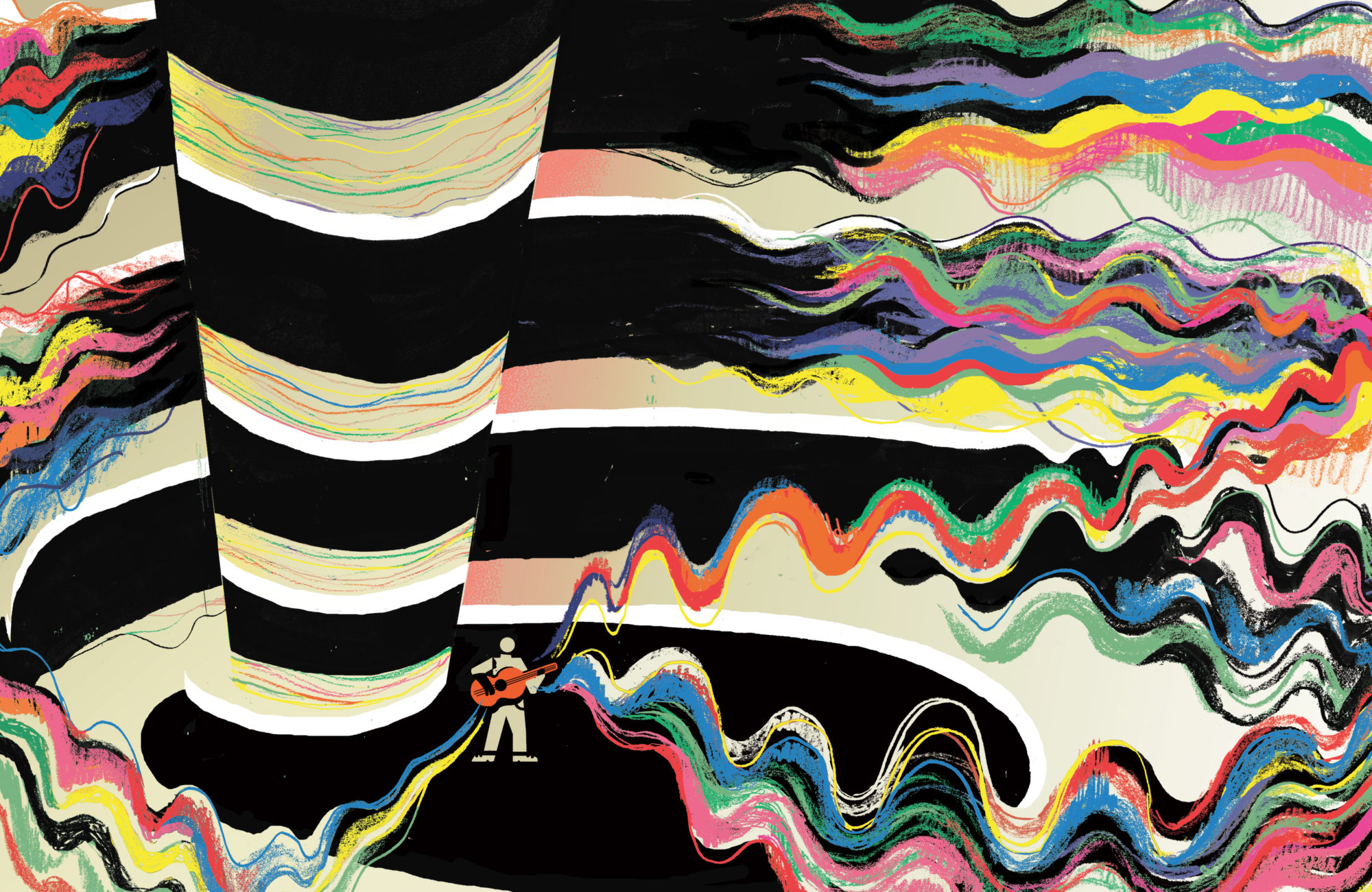

Of late, I’m taking this to extremes. I like the idea of responding to your environment, not forcing your agenda as a musician on a space, but listening for the feedback and then deciding what to do. I do this each night on tour, when playing a different room, whether it’s a cathedral, a black-box rock club, or an arena. My Echolocations project is all about this. I took to the outdoors, both natural and man-made environments. I’ve recorded in the Coyote Gulch canyons of Utah, the Los Angeles River underneath the Glendale-Hyperion Bridge, the Marin Headlands north of San Francisco, and a stone-covered aqueduct in Lisbon. The reverb in some of these places can last for 10 to 15 seconds.

The idea is to go with no agenda and hear what the space wants you to play, and then build a composition based on that. For instance, in Utah, I discovered that the C-sharp gave me the most information about where I was and placed me in that space. So I built the entire composition on C-sharp and these sometimes sweeping motions. At every space, I just experiment and build a sonic map around it.

Playing in domed or circular spaces, like the Guggenheim Museum in New York or the Masonic Temple in San Francisco, is particularly tricky. When I played at the Guggenheim, there was a breaking down of the fourth wall. The audience was on the spiral above me and right behind me at the beginning of the ramp. It was really weird. Someone could have just casually tapped me on the shoulder and asked me questions while I was trying to play. I’m used to facing the audience. I like hecklers or people interjecting—that I look forward to. But something about having people behind me was weird. The Guggenheim, though spectacular, is a very neurotic environment to play in. By contrast, the Congregation Sherith Israel synagogue in San Francisco is also circular, but it’s one of the most glorious-sounding spaces I’ve ever played in, because the dome, it turns out, has a choir loft around it.

I also find it interesting to write songs in different types of living spaces. Once, I turned a Midwestern high-ceilinged barn on a farm into a live-work space. I discovered that the music I was making out there was different than what I was making in typical apartments in Chicago, where I lived at the time. I find high-ceilinged rooms make one more optimistic—which is generally good for making music. Misery is not ideal for music-making. The smaller the room, the more sleepy a record might sound.

I just got back from playing in a jazz hall in San Francisco and it was completely controlled—a lifeless room. I was really exhausted after every show, pushing and pushing, trying to get some sort of lift-off from the space. The next night, we were at the cathedral-like Bing Concert Hall in Stanford, California. At Bing, it was effortless—I was just swimming in sounds.

The point is, I’m very open to architecture. It’s a practical part of my job.

The author is a Los Angeles–based musician. His latest album, Echolocations: River, was released by Wegawam Music this fall.