No artist wants to hear their work has fallen into disrepair, but that is exactly the news Mary Miss received this past October. The pioneering land artist’s environmental installation Greenwood Pond: Double Site (1996), located at the Des Moines Art Center and considered the country’s first urban wetland project, would soon close to the public because its dilapidated components were severely weathered from the elements and at risk of collapsing. Six weeks later, director Kelly Baum estimated the repair costs would spiral to $2.7 million, and decided to dismantle the artwork entirely.

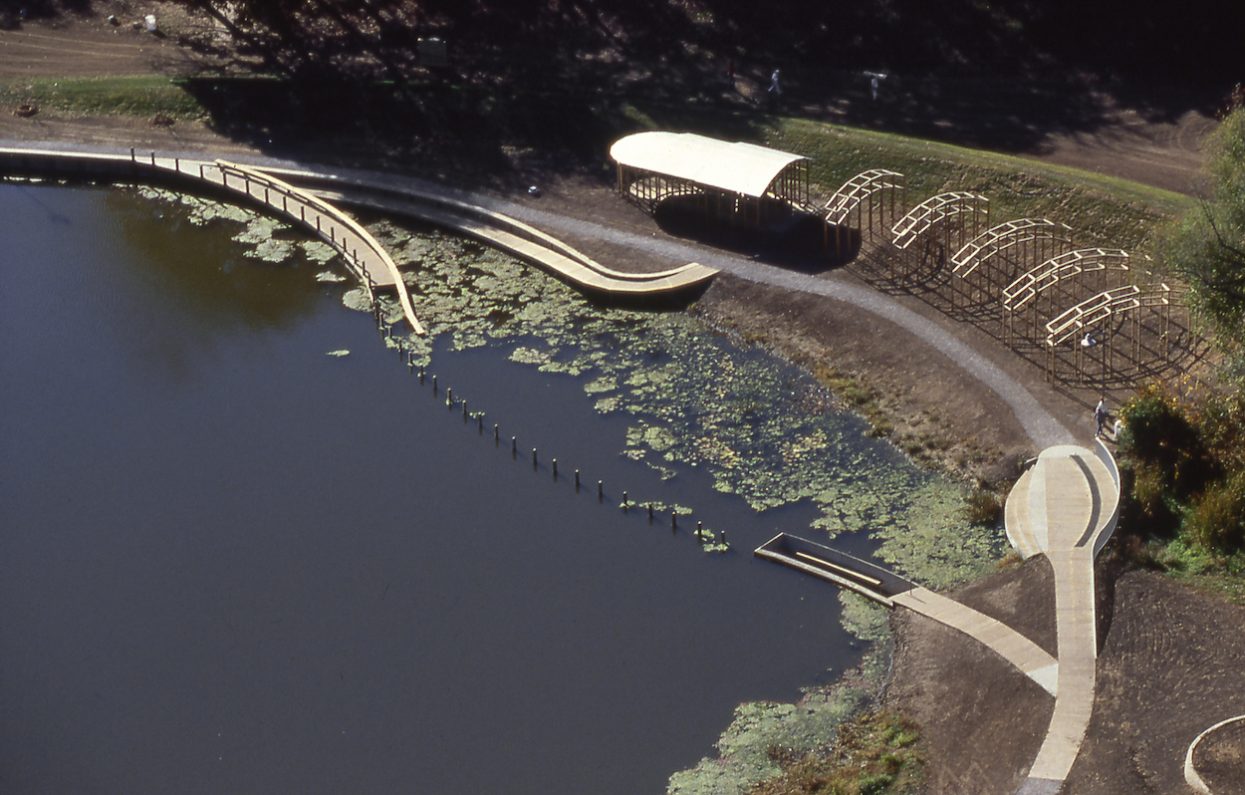

Despite an outcry, the institution intended to proceed with demolition plans. That was until Miss filed a lawsuit this past week seeking to prevent the museum from dismantling the work, which features boardwalk paths leading visitors up and down ramps around the edge of a quaint lagoon flanked with architectural follies. In her complaint, Miss alleges the museum is violating the Visual Arts Rights Act of 1990, which grants artists the right to prevent the destruction of works with recognized stature. A federal judge granted Miss a temporary restraining order, which the museum acknowledged with an announcement that it would pause demolition work and temporarily fence off the more dangerous sections.