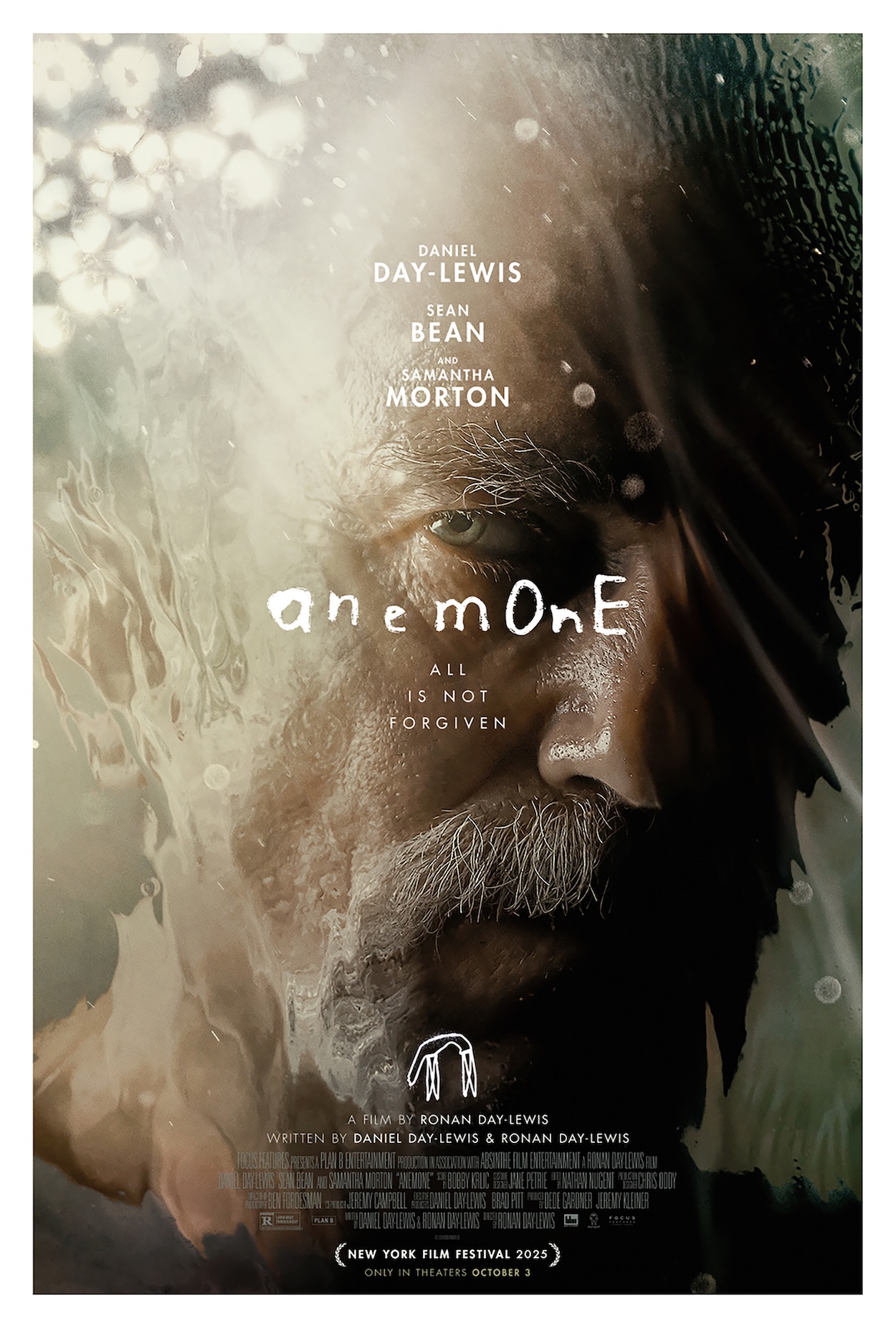

With a painterly touch, fine artist and filmmaker Ronan Day-Lewis composed the tone, texture, and atmosphere of Anemone, his feature directorial debut. An anxious, tactile artwork, the film carefully peels back the layers of a relationship between two brothers—Jem (played by Sean Bean) and Ray (portrayed by Daniel Day-Lewis, who co-wrote the film with Ronan). Interwoven personal histories fray under the pull of one primary location, a remote cabin enveloped by forest, where two powerful acting performances bring a familial mystery to light.

Ronan Day-Lewis On His Feature Directorial Debut, Anemone

BY DAVID GRAVER October 27, 2025

The 2025 New York Film Festival hosted Anemone’s world premiere, which Surface attended as the guest of official partner Rolex, before the Focus Features film screened at the BFI London Film Festival and opened in theaters in the U.S. and the U.K. Simultaneous with this, Ronan presented a suite of new paintings in his debut solo exhibition with Megan Mulrooney, “Anemoia,” which runs through November 1. Both the filmic and painted works apply a surreal sensibility to decidedly human subject matters.

Though driven by unease and apprehension, the story of Anemone comes to life through the sensorial cinematography by Ben Fordesman, which depicts the subtle movement of hands to sweeping scenes of trees in the wind. “I wanted to find ways of joining this intimate, almost suffocating human story with something larger and mythic, at times beyond the awareness of the characters,” Ronan tells Surface. “The way we photographed the natural environment was essential to this, and the cutting—when we would give ourselves permission to depart from the human drama and make the audience aware of something stranger and more mysterious happening at the fringes of this world.”

The concept of a location as a character functions two-fold here—with the confines of the cabin acting as a pressure cooker, and the outside world offering space for secrets to spill and feelings to emerge. Moments by the sea and a trek through a glowing, abandoned amusement park lend beauty and mirror emotional arcs. “We’d first decided to look at Anglesey off the coast of Wales as the setting partially because the script called for a beach directly abutting the forest, for the exploratory sequence where Jem first starts to get a sense of Ray’s environment and they emerge from the trees directly onto the sand,” Ronan explains.

“There was a beach on the island which seemed to fit that description. It was the first location we looked at and it was eerie how precisely it matched what I had imagined. These uniform rows of tall, spindly trees just ended abruptly before these dunes covered in long silky grass. The shore itself was vast and completely empty, and the water was totally still that day, and there was this feeling that you were standing at the edge of the world,” he says.

“Wind was written into the script, but mostly in the sound design, only once visually,” he continues. “We knew we’d have to manufacture a huge current of wind in the beginning of the film, and I had sort of thought of that as an isolated incident. But I didn’t realize that the wind on the island would be incessant. We decided early on to be alive to that. Most of the wind you see in the film is real.”

Mark Walledge, the supervising locations manager, led the search for a wooded area where they could build the film’s cabin. “We were walking around one of these when we saw something through the trees, a bit of a stone wall, and we went toward it and stumbled out into this circular clearing which was the exact size and shape as the clearing described in the script,” Ronan says. “There were the bones of this very old looking stone structure at the edge of the clearing which was the exact dimensions for the hut.” This discovery was woven into Ray’s backstory.

Ronan accented two scenes from the film—both moments of surrealism, one an epiphany—with a quadruped creature that appears in some of his painted pieces. For anyone familiar with his paintings, it feels like an artistic exclamation point, or the establishment of a unified otherworld. “I think of painting and film as two expressions of the same impulse,” Ronan says. “That impulse can be mysterious.”

A complex creative current passes between the film and the Megan Mulrooney exhibition. “I was pulling from Flickr photos from the early two thousands, thinking a lot about collective memory and of wanting to inhabit other lives and of this body of work as the seed of another film,” Ronan says of the source material behind this series of paintings. “But I was also making that show in a room above the cutting room while editing Anemone, painting at night and through the weekends, so the images and the overall feeling of the show were heavily influenced by the world I was entering downstairs.”