When Gayane Umerova—the Commissioner of the Bukhara Biennial and Chairperson of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation—asked, “How do we get people in the country every two years, and why? How can we keep them excited?” The answer was easy: a biennial. “If you come back every two years, you can come into the process of getting to know a place and get deeper than a one-time visit,” said Diana Campbell, the biennial’s artistic director.

Discovering “Recipes for Broken Hearts” at the 2025 Bukhara Biennial

Over 200 artists from 40 countries participated in the first Bukhara Biennial, running through November 20.

BY ANN BINLOT September 24, 2025

In a world saturated with visual arts biennials—with some estimates counting nearly 250—do we really need another one? The answer is no, unless it can genuinely enrich its place, the artists, and its visitors. The inaugural Bukhara Biennial did that: it unveiled a breathtakingly beautiful ancient region still largely untouched by mass tourism, fostered meaningful exchanges between artists and local craftspeople, and introduced contemporary art to entirely new audiences. We arrived in Bukhara on opening day, September 5. Five days later, we left transformed, deeply moved, and inspired.

Set across Bukhara’s Old City, the biennial transformed ancient mosques, madrasas (centers for learning much like a university is today), and caravanserais (accommodations for merchants) into exhibition spaces for contemporary art. The thematic starting point of the biennial was a popular folk tale in Uzbekistan that led to the creation of plov, the national dish that’s cooked in a large cast-iron pot called a kazan. First, onions and some sort of meat, usually lamb or beef, are sautéed in a savory fat or oil before carrots, spices like cumin, coriander, and barberries are added, and, finally, rice and water.

Legend has it that plov was invented by Avicenna, an ancient physician and philosopher who created the dish to cure the broken heart of a prince whose family forbade him from marrying his true love, the daughter of a craftsman. Unable to eat, Avicenna created a recipe to nourish the prince back to health after losing his appetite over the grief from his heartbreak. The story culminated into Recipes for Broken Hearts—the theme of the 2025 Bukhara Biennial.

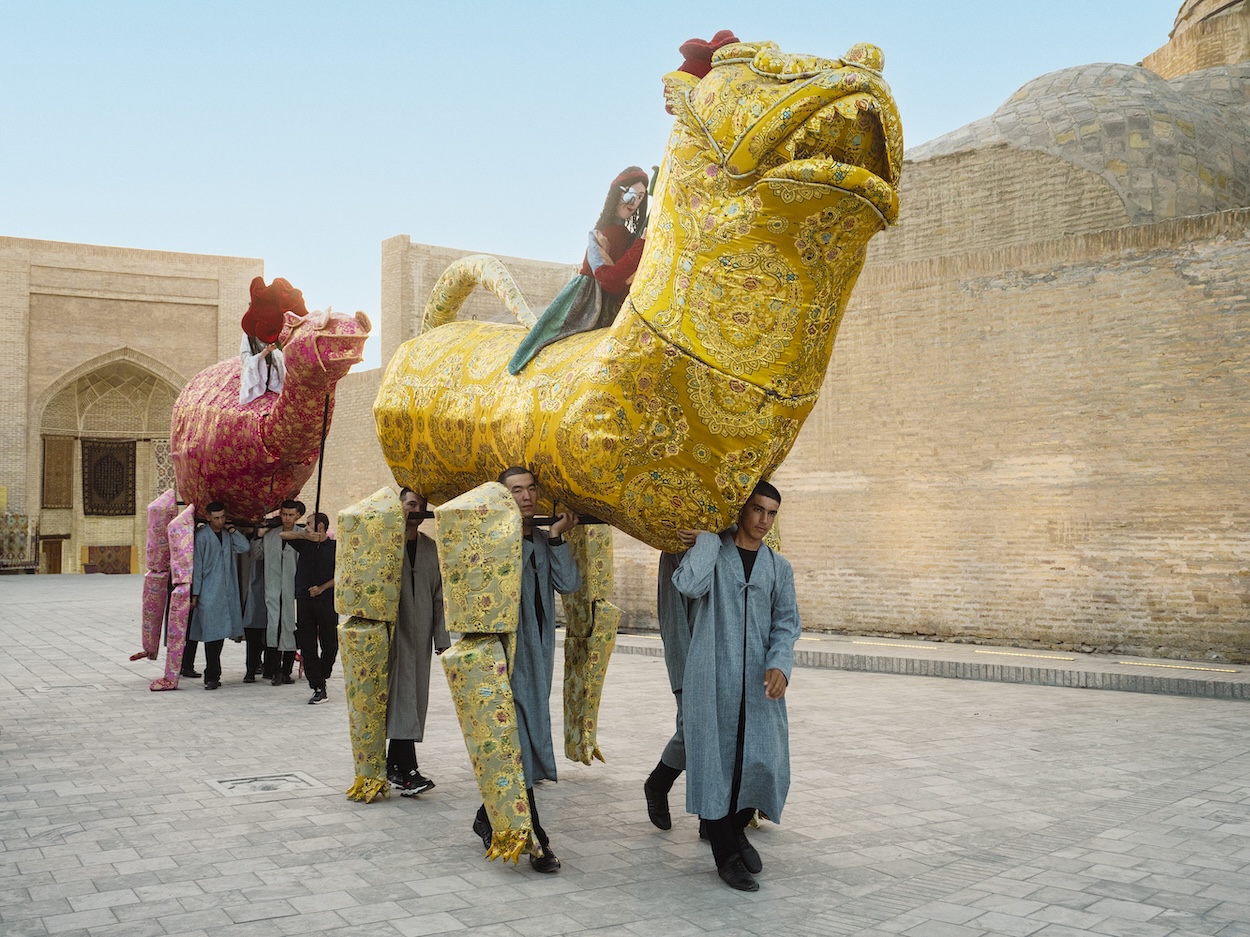

Campbell set this exhibition apart with the following requirement: participating artists had to partner with local craftspeople to highlight the city’s rich traditions spanning textiles like ikat silk and suzani embroidery, carpet weaving, gold-thread embroidery, ceramics, mosaics and tiles, wood carving, puppet-making, miniature painting, calligraphy, jewelry, leatherwork, musical instrument making, and more.

Food was a large element of the exhibition. German artist Carsten Höller brought Café Oshqozon, a pop-up of his Brutalisten restaurant, to Bukhara, to the 19th-century Abudurahmon Alam Madrasa. The collaboration between the artist and Brutalisten head chef Coen Dieleman from the Netherlands, Italian chef Daniele Puricelli, and Uzbek chefs Bahriddin Chustiy and Pavel Georganov yielded a 12-course menu that included plates like a Brutalist Uzbek Tomato Tower, highlighting one of the stars of Uzbek produce featuring a fermented tomato juice base topped with a totem of tomatoes, tomato skin, and sundried tomatoes, along with a Brutalist Melon Moment, a refreshing sorbet made using melons from the Slavs & Tartars installation across the square, and for meat lovers, Brutal Three Fingers (Uch-Panja), a kebab layering meat and tail fat on three skewers.

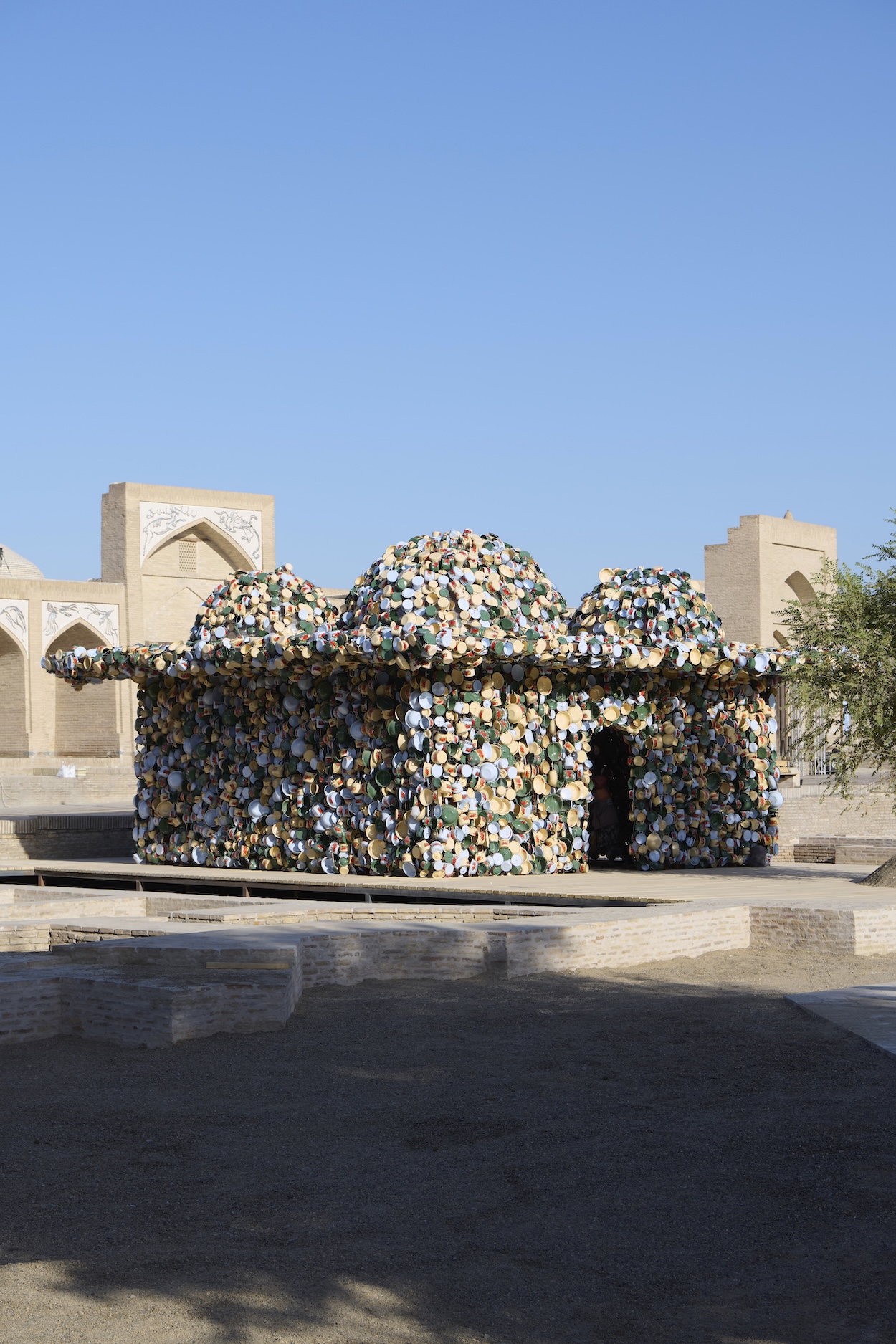

Indian artist Subodh Gupta installed a pavilion just outside the Ayozjon Caravanserai meant as a place for gathering and eating. Taking inspiration from the shape of Magoki Attori, the oldest standing mosque in Central Asia, Gupta covered it in the vibrant enamel Ikat souvenir plateware. “Together. We make a recipe for the broken heart,” said Gupta before serving a meal starting with dishes like a Velvety Red Lentil Shorba, and a Golden Petite Samosa, followed by a Rasa Thali, and for dessert, a creamy steamed yogurt topped with saffron. “I want you to hold this memory, this story, together and carry by the lens.”

At Gupta’s lunch, we found ourselves sitting next to the Turkish-American artist Vahap Avşar, who told us how he worked with Uzbek wood carver Firuz Shamsiyev and the Uzbekistan Beekeepers Association to create two snow leopards of reclaimed wood hanging along walls in the square that also function as habitats for bees. “I researched the environmental issues here in this region,” he explained. “The snow leopard is treasured as a spirit animal and it’s endangered badly. I immediately thought, I want to make snow leopards out of wood and have a beehive in the belly.”

At the entrance of the Gavkushon Madrasa sits a small house of rock sugar Egyptian food artist Laila Gohar created in collaboration with Uzbek Ilkhom Shoyimkulov and Ariel André, the French architect and designer behind Paris-based studio Golem. Inside, a canopy and benches by architect and designer Suchi Reddy woven with the help of Uzbek weaver Malika Berdiyarova create a place to convene and rest, providing shade from the heat.

Each area features a different exhibit, from Bahamian artist Tavares Strachan’s rugs made with Uzbek carpet weaver Sabina Burkhanova that pay homage to poet Langston Hughes’ time there in the 1930s. “Blue Room,” one of the biennial’s most magnificent (and Instagram-friendly) installations, by Uzbek ceramic artist Abdulvahid Bukhoriy, made with master coppersmith Jurabek Siddikov highlights Bukhara blue, the city’s signature hue that’s somewhere between cerulean and turquoise, through a tiled room surrounding a suspended sculpture inspired by the healing ritual where fish absorb human illness. Uzbek artist Davlat Toshev featured marbled paper, transforming two rooms into an immersive painting, showcasing the region’s pomegranates.

To the left of the Madrasa, Kazakh bio artist Dana Molzhigit erected a striking abstract installation of soil and living organisms in petri dishes along the wall’s arched niches. She worked with five laboratories, using organisms with healing properties, like spirulina and cyanobacteria. “It was a wonderful experience for me because it was a deep dive to the heart of the Uzbek culture,” said Molzhigit. “Because I’m Kazakh, I didn’t know a lot about craftsmanship here.”

The Khoja Kalon Mosque provides a stunning backdrop to a series of installations in architecture designed by Claudet. Enter through a turmeric-infused pyramid by Colombian sculptor Delcy Morelos woven by Uzbek craftsperson Baxtiyor Akhmedov with jute threads before arriving at a labyrinth of human forms by British sculptor Antony Gormley made with mud bricks with the help of Bukharan restorer Temur Jumaev. To the right is an area where Buddhist monk and chef Jeong Kwan ferments kimchi with the local community. Follow the path up the ramp, where dunes hide flower gardens by Uzbek artist Ruben Saakyan made with Russian biologist Konstantin Lazarev. Look above and see Kyrgyz artist Jazgul Madazimova’s incredible spine made of colorful scarves from the women of Bukhara, telling the story of every woman’s hopes, dreams, and struggles, along with the strength and vulnerability within them.

Our last day in Bukhara culminated in a temple meal inside Gupta’s structure, made by Kwan and Gupta, a fusion of Korean and Indian temple food. A Muslim emir, a Jewish rabbi, a Buddhist monk, and the governor attended the intimate lunch. It doubled as a symbol of healing, and a recipe for the heartbreak and suffering currently going on in the world. “It’s a place of so much cultural mixing, religious mixing, spiritual mixing,” explained Campbell.

Captivated by the ancient architecture, enriched by the contemporary art, and uplifted by new friends from Bukhara and beyond, we left the ancient SIlk Road city feeling restored.