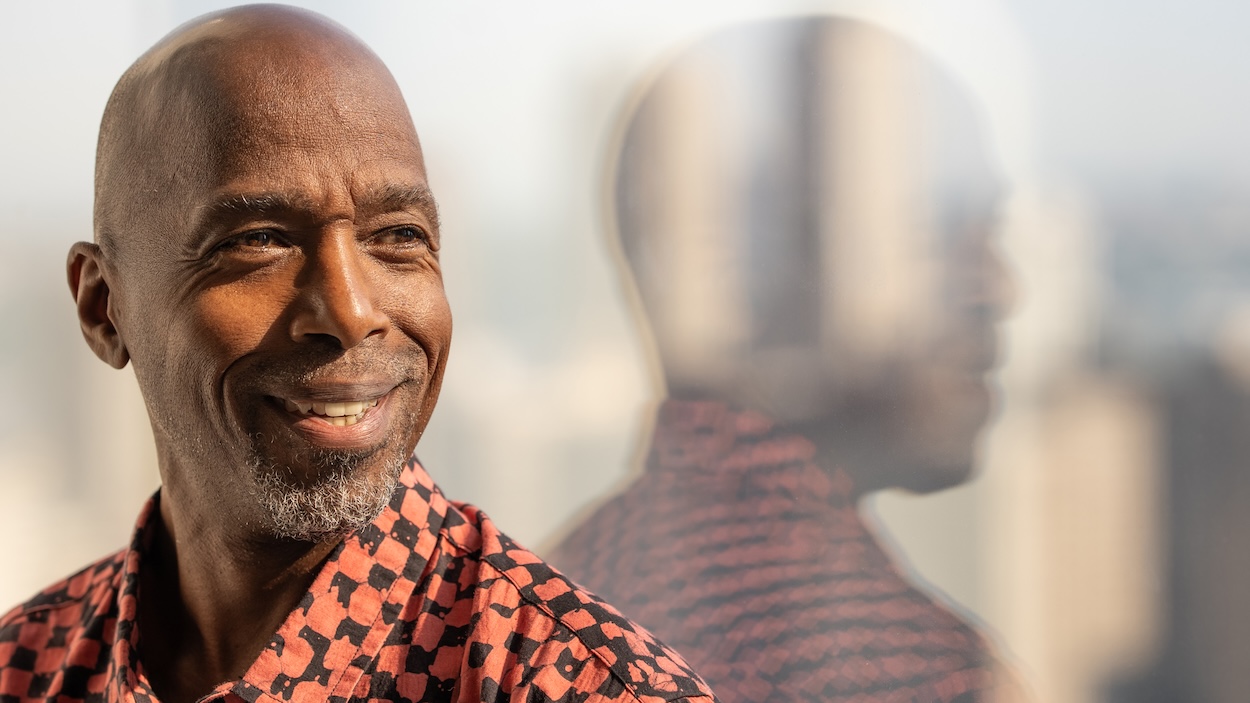

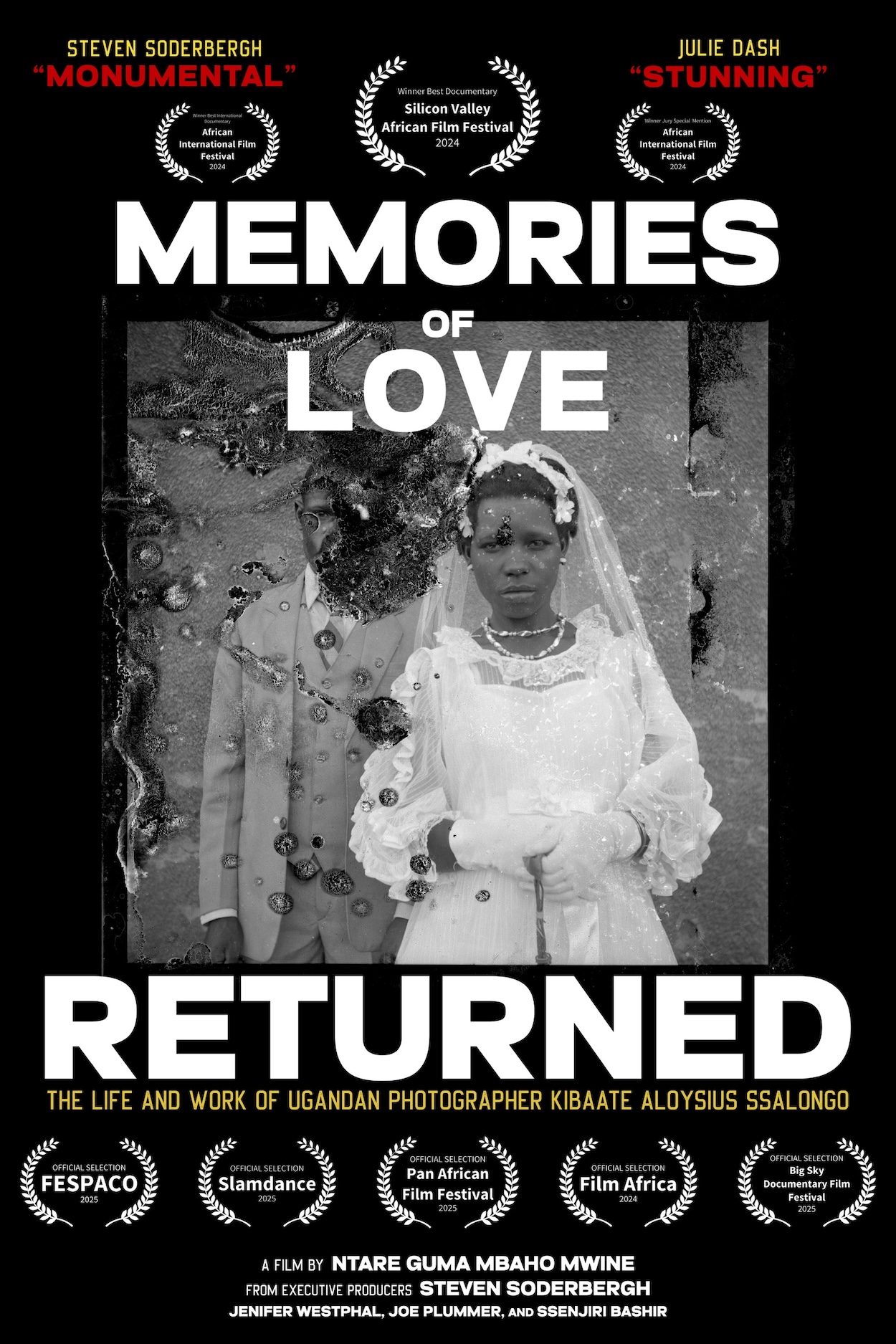

In the small town of Mbirizi, Uganda, Kibaate Aloysius Ssalongo photographed his community from the late 1950s until his death in 2006. On April 24, 2002, actor and filmmaker Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine’s car broke down in Mbirizi—and while he waited for its repair, he stumbled upon Ssalongo’s studio. This chance happening inspired “Memories of Love Returned,” Mwine’s love letter to Ssalongo’s practice and immense impact, as well as the large-scale outdoor posthumous exhibition he held on the photographer’s behalf.

Chronicling More Than Two Decades, a Documentary on the Power of Photography in Uganda

“Memories of Love Returned,” by filmmaker Ntare Guma Mbaho Mwine, looks at the life and work of late local photographer Kibaate Aloysius Ssalongo

BY DAVID GRAVER August 05, 2025

Produced by Academy Award-winning director Steven Soderbergh, the documentary does more than depict Ssalongo’s photographic contributions and decipher their deeper story. The narrative also explores the role of photography in Uganda—then and now—and weaves in Mwine’s own story. Of greatest importance, the film carefully addresses the complexity of family and legacy.

“Memories of Love Returned” premiered at the Silicon Valley African Film Festival late last year; it won best documentary. Since then, the 77-minute film has toured from Slamdance to the New York African Film Festival at Film at Lincoln Center and the Zanzibar International Film Festival (where it also won best documentary). In September, it will screen as part of the Africa Foto Fair in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. Meanwhile, three projects featuring Mwine—AppleTV’s “Smoke,” Paramount+’s “Dexter: Resurrection” and Hulu’s “Washington Black”—have had their own premieres. And yet “Memories of Love Returned” continues to resonate for its nuanced storytelling and emotional resonance. Below, Mwine guides Surface through his filmmaking experience.

With chance being so fundamental to this story, can you tell us about your relationship to the concept of fate?

I’ve been thinking about this a lot. So much so that I recently bought C. G. Jung’s book “Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle” to do a deeper dive into the moment something other than the probability of chance is at play. In it Jung points to an underlying unity between the inner world—one’s psyche—and the outer world. He suggests that the two are not separate but can reflect or mirror one another in mysterious ways.

It was a chance meeting with Ugandan photographer Kibaate that changed both our lives in ways I am still processing. I am now in the midst of another chance alignment having three new series on the air at the same time. Only time will tell what lasting impact this will have.

What was it that immediately caught your attention about Kibaate Aloysius Ssalongo and his photo studio?

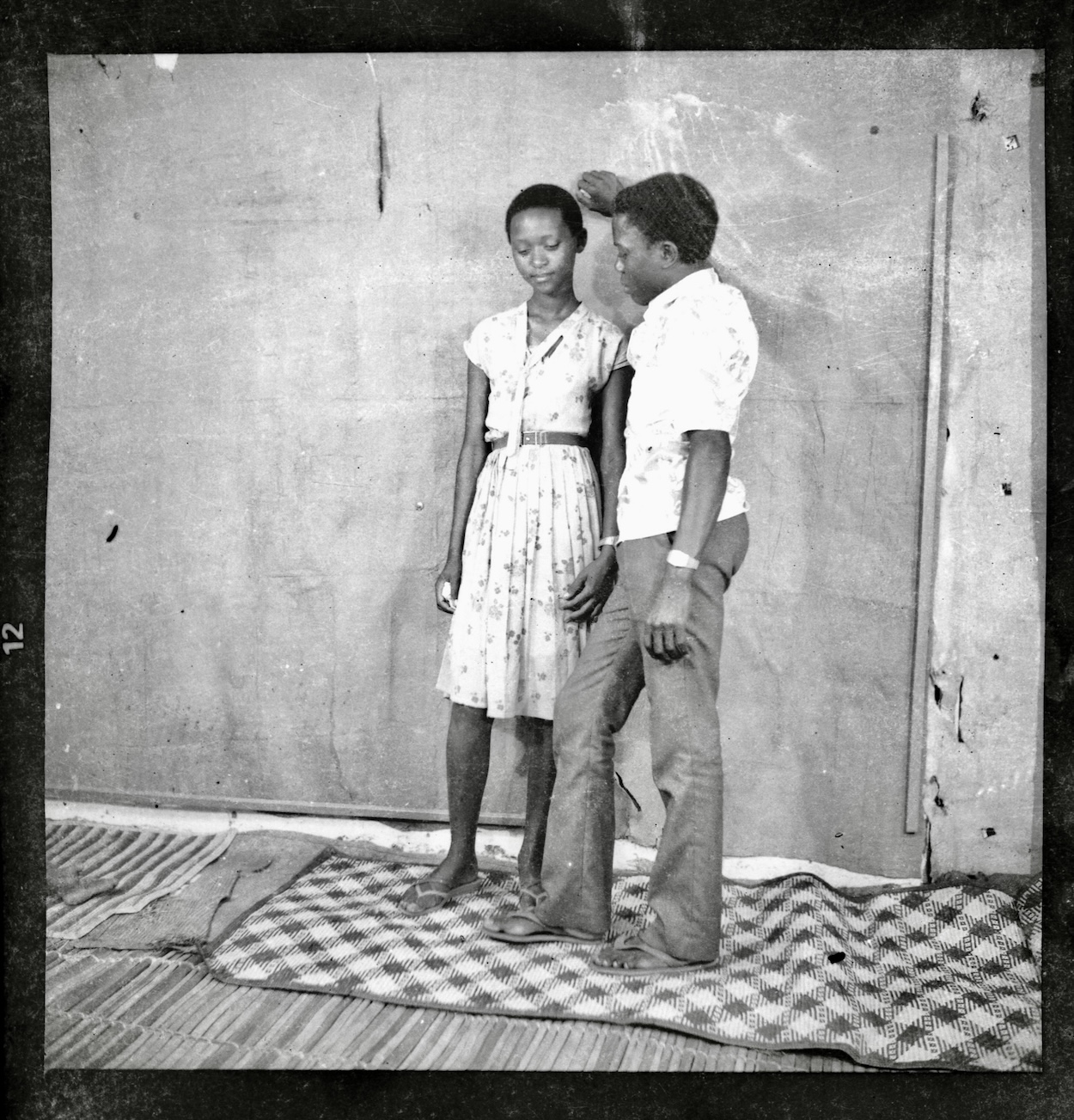

It was the first rural Ugandan photo studio I had ever seen. Kibaate had a full set up of lights, a darkroom and over five decades worth of negatives in every corner of his studio. I was blown away.

Why did you walk in?

His photo studio sign hanging outside is what immediately drew me in.

And then why did you continue to return?

I was curious about his life and work. There was also no way to get through his five decades of photography in one visit.

You probe many sides of Kibaate. Did your perception of him change over time?

My perception of him did change over time. His life seemed simple when I first met him. But the more time I spent with him, the more I came to see the complex web of personal and professional entanglements he was navigating.

When did you know you wanted to make it a film?

I filmed our meetings at his studio just to have a record of his vast archive and knowledge. But it wasn’t until his unexpected passing that I realized how fortunate I was to have documented our meetings. Those early recordings became the springboard for the full length feature film.

In many ways, you are acting as a steward of Kibaate’s legacy—and the legacy of each and every subject, as well as his family members. How closely were you thinking about that while making this film?

I was haunted by Kibaate every step of the way. I made a promise to him while he was alive that I’d find a way to share his work far and wide. Unfortunately he passed away before I could keep that promise and that weighed heavily on me. So I am all the more grateful I was able to complete the film. I am still working to keep my other promise to make a book on his life and work, which I am in the process of completing.

How did you craft this narrative to also inform viewers about Uganda today?

The film is anchored in the present day Ugandan landscape while mining a long lost past of love, loss and family secrets.

As a filmmaker, how did you begin to weave all of the elements of this story together—including your own personal narrative?

One of the biggest hurdles was translating and transcribing the hours and hours of interviews that were conducted over the years of filming. Once I had that done I was off and running cutting and pasting dialogue to create the bones of the film. I was then able to write the needed voice over and film any needed pick ups.

Can you speak to Soderbergh as a producing partner?

Soderbergh was the ideal producing partner. He gave me the financial support to mount Kibaate’s large-scale outdoor exhibition in his hometown and document that process. His support came with no strings attached. The only thing he ever asked of me was whether I needed anything else. He was always responsive in the most supportive way whenever I checked in with him.

It’s in the middle of the festival circuit. How important is that to the film?

The festival circuit has been an incredible platform for the film to connect with audiences, build momentum, and gain awards recognition—something I feel extremely fortunate to still be experiencing.

Why was it important to you to have the LGBTQ+ or even same-sex friendship storyline here?

Kibaate documented the lives of same-sex friendships. Given Uganda’s harsh anti-gay laws I felt it was important to not sweep those stories under the rug.

The name of the film is explained through the act of letting people have their images. Was that always part of the idea when you were plotting the art exhibition in the gas station?

When I was a child living in Stockbridge, Massachusetts my mom decided to move back to her childhood home in Uganda. Most of our family photos were lost during this move. I’ve often imagined what it would be like to be reunited with these lost photos. So it was always my intention that Kibaate’s photos be reunited with his subjects or their family members. That was the primary reason I mounted Kibaate’s exhibition in his home town.