Emily Noyes Vanderpoel (1842–1939), a color theory pioneer you’ve probably never heard of, accomplished much during her 96 years. An American painter, writer, and philanthropist, Vanderpoel worked mostly in watercolor and oils. She attended the Art Institute of Chicago, and her work was later exhibited nationally, including at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and is part of the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum’s permanent collection. She also served as vice president of the New York Watercolor Club, an organization founded in response to the American Watercolor Society’s refusal to accept women as members. (One could argue that the more inclusive club’s jury-selected exhibitions, which implemented stricter standards for the work they presented, helped raise the bar for watercolor painting.) But her biggest achievement took the form of a book, titled Color Problems: A Practical Manual for the Lay Student of Color.

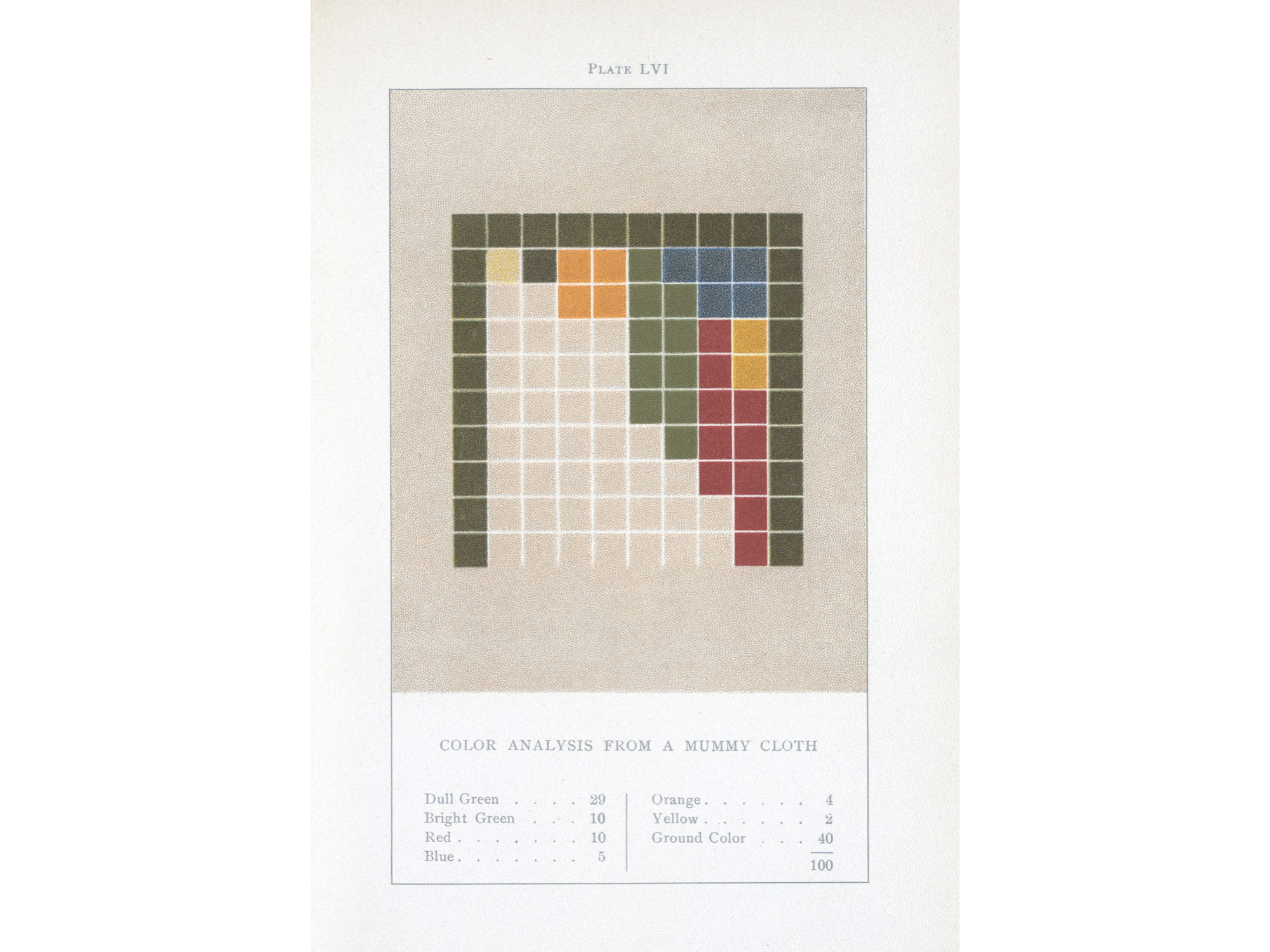

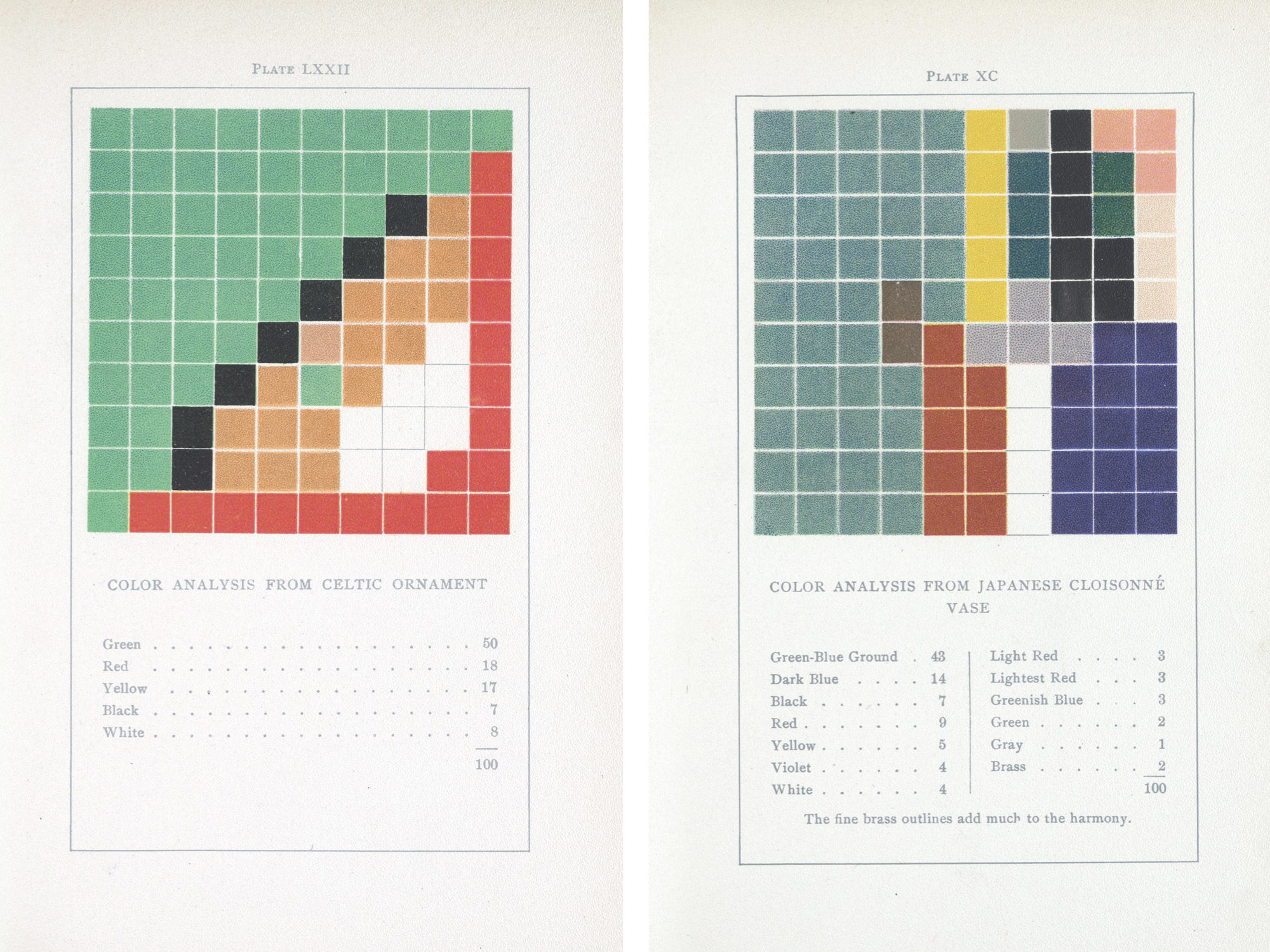

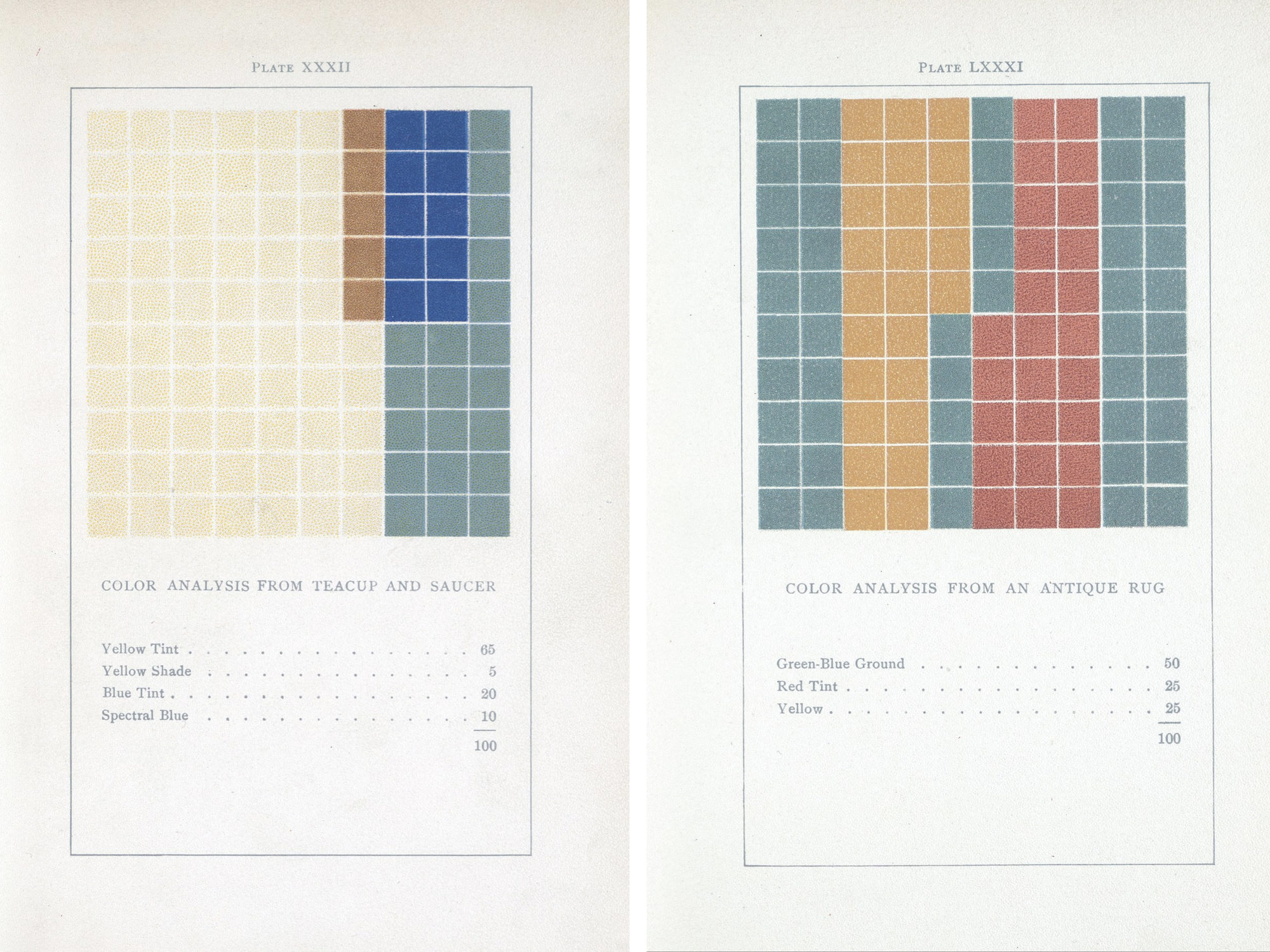

Color Problems had been largely forgotten, until now: Brooklyn-based publisher The Circadian Press, in partnership with Sacred Bones Books, recently launched a Kickstarter campaign to reprint the book for a November release—quickly surpassed its fundraising goal by a considerable sum. First published in 1901, the 400-page opus provides a comprehensive overview of color theory—principles of working with color that consider color mixing and the visual effects of specific color combinations—at the time. Her user-friendly yet meticulous, research-based approach was later made famous by men, and is now ubiquitous in art and design curricula everywhere—though Vanderpoel, and Color Problems, are typically never mentioned. To illustrate concepts explored in the text, Vanderpoel included 117 color plates, created on a 10×10 grid, that analyze the color proportions of actual objects, many from her personal collection. She fleshes out a bunch of azaleas, the eye of a blue jay, a slice of an orange, a butterfly, tree fungus, and a mummy cloth (pictured above), among others. The plates display an aesthetic decades ahead of its time in a format that anticipates Josef Albers’s “Homage to the Square,” which was initiated more than 50 years later. Her process for creating them remains unclear, but her pared-down, geometric way of expressing color is nothing short of remarkable.