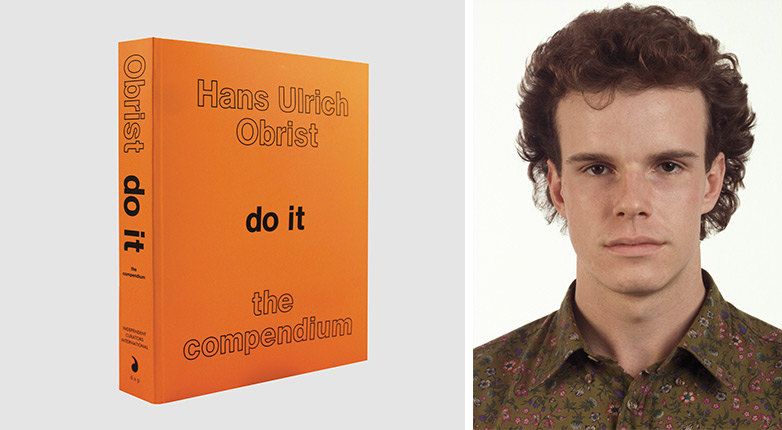

Few have mastered the art of conversation better than Hans Ulrich Obrist‚ co-director of exhibitions and programs and director of international projects at London’s Serpentine Gallery, who, through his ongoing Interview Project, has recorded some 2,000 hours of his discussions with notable cultural figures. How, then, does one interview an ace interviewer? Surface tapped Paul Holdengräber, director of the public-talks series Live From the NYPL, for the engagement. He, like Obrist, has interviewed hundreds of personalities from numerous professions and walks of life; guests at the forum have included Patti Smith, Anish Kapoor, and Mike Tyson. Holdengräber spoke with Obrist about the curator’s early influences, his current projects, and the con- cept of the gesamtkunstwerk, a work that integrates and unifies all forms of art—or at least attempts to. The comprehensive nature of such a work ultimately makes it an unrealizable ideal, something to perpetually strive for but never complete, which is precisely the quality that makes it interesting to Obrist. Indeed, many of the curator’s undertakings— his Interview Project, his “Do It” exhibition, and the Serpentine Marathon series, to name a few—are works perpetually in progress; they’re always being added to, reinvented, and remade.

Paul Holdengräber: I would like to start with what I take to be your ravenous, all- consuming appetite. Dorothy Parker’s line would fit perfectly for you: “The cure for boredom is curiosity. There is no cure for curiosity.” Talk to me about curiosity and the fact that there may be no cure for it, except perhaps curation or just talking constantly.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: It’s interesting that there is this connection between curating and curi- osity. It goes back to my childhood. My parents, when I was 3 or 4 years old, took me to the library of the Abbey of Saint Gall, one of the great medieval monasteries of the world. It burnt down and then was rebuilt, and it became this fabulous Rococo library. It made a huge impression on me: this display, this time capsule, where one could look at these books only with white gloves on. Later, when I was 7, 8, and 9, my parents kept going back to it. This was before I ever saw art. I realized little by little that these monks were bringing all this knowledge together. That was the beginning of it somehow.

PH: Napoleon once said of one of his generals that he knew everything, but nothing else.

HUO: I didn’t grow up at all in the context of museums, and I didn’t grow up at all in the context of the arts. The only place that my par- ents took me to that was a kind of museum was that monastery library. Then, at a certain moment, being completely ignorant about art, I came across a sculpture by Giacometti at the Kunsthaus in Zurich. That had such a magnetic impact on me that from then on I started to go to museums every day.

PH: That’s a curious use of the word “magnetic.” It implies that there is an attraction so great that you stick to something.

HUO: That’s exactly what it was. My ignorance of art developed into this magnetic, almost addictive eternal return. I went back every afternoon when there wasn’t school to look and look and look and look again. It was like a school of seeing. It was a very lucky situation, because I think a city without a museum is a dead city. I really think that a dynamic museum—a museum as a laboratory—is as important as a great school in a city. The Kunsthaus in Zurich, at that time, with the visionary curator Harald Szeemann, became my school. I learned much more there than in any other school. I visited his “Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk” exhibition 41 times as a teenager.

PH: How do you recall that it was 41?

HUO: Because I counted it.

PH: That says something about you, I would say. Forty-one times—it makes me think of the Talmudic idea that there are 47 layers of meaning, and that in some way you had to go back again and again to see, see, see, look, look, look. It reminds me of what Werner Herzog tells his stu- dents when they want to learn about film. He says, “Read, read, read, read, read!”

HUO: One can look and look and look again. It’s one of the main criteria of why something is a great work of art: that it’s sort of inexhaustible, and there can be, over the centuries, dif- ferent interpretations. That’s sort of the big paradox of the exhibition, which became my medium. With a limited life span, works can last forever.

PH: Let’s go back to those early years. You mentioned you were 3 or 4 years old when your parents took you to that mon- astery. It was kind of a wunderkammer. Is that correct?

HUO: I remember that one had to wear felt shoes. There was this silent walking through the space.

PH: So it created the sense of entering into a sacred space.

HUO: I suppose early childhood experiences with books had to do with discovering the world and trying to bring different forms of knowledge together.

PH: Books have mattered to you greatly, both as books written by others and the infinite variety of books you yourself curate or write.

HUO: I’ve always believed that books grow out of other books. There were many things that happened in my childhood in Switzerland that were influential. On my way to high school, when I was 13, 14, 15, 16, there was the house of Ludwig Binswanger, the psycho- analyst and founder of Daseinsanalysis, who influenced Foucault. I would pass by this abandoned house, and I decided to investigate. I found out it was the house where Binswanger had his clinic. It was, in my teens, a second connection to the idea of the atlas, of the encyclopedia, of connected images and how they produce meaning.