Over the past few decades Miami-based real estate developer and art collector Jorge Pérez has played his cards right. Not surprisingly, cards—specifically dorm-room poker—was how Pérez got his start as both an entrepreneur and a collector. With his first payouts, he bought works by Marino Marini, Joan Miró, and Man Ray; the winnings also allowed him to start several profitable side businesses. His passion, or some may say obsession, for collecting art has continued apace ever since. Today his name is attached, somewhat controversially, to the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), formerly the Miami Art Museum, and his company, the Related Group, has amassed an impressive collection, which it loans out, stores in an off-site facility, and blankets throughout its headquarters and various developments. All of the works in both Pérez’s personal and Related’s corporate collections will eventually go to the museum.

Though Pérez collects widely, the majority of the works are by Latin American artists—a direct connection to his roots. Born to Cuban parents in Argentina, he grew up there until he was 9; from there, the family migrated back to Cuba and, following the revolution, was exiled to Colombia, where Pérez lived until coming to the U.S. in 1968 to attend Miami-Dade College. Later, at the University of Michigan, Pérez studied urban planning, and though he’s now well heeled and clearly a savvy businessman—his net worth is estimated at $3.6 billion—that wasn’t always necessarily the case. His early career was as a community- minded Miami city planner, working mostly on low-income housing, a position that led him to consulting and eventually developing market-rate apartments. These days, Pérez collaborates with some of the world’s top architects, designers, and artists, including Enrique Norten, Yabu Pushelberg, and Piero Lissoni, to create mixed- use projects gorged with amenities and multimillion-dollar apartments.

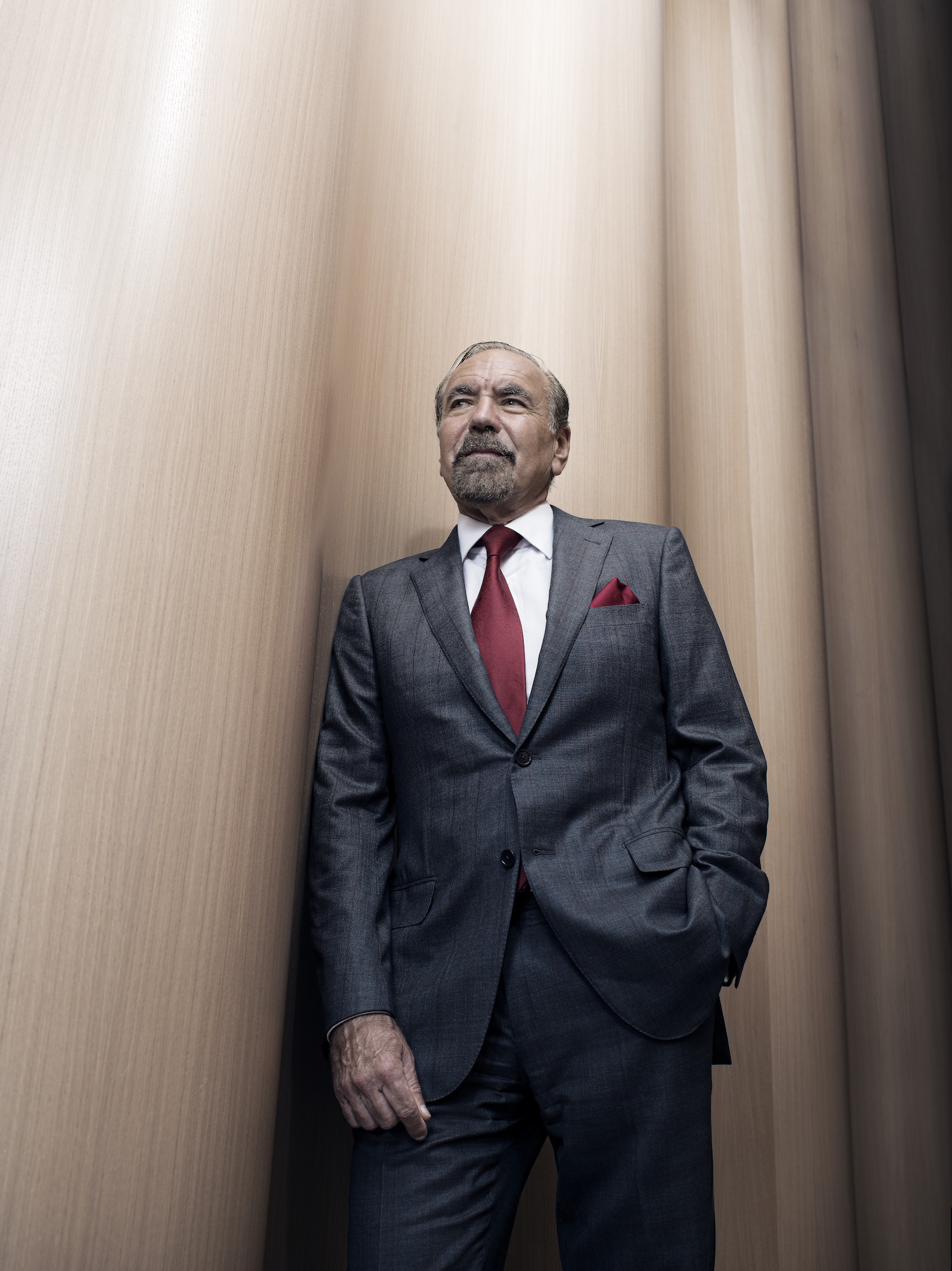

Surface recently met with Pérez at his art-filled office in downtown Miami to discuss his early gambling days; the inherent tensions in collecting; and why Donald Trump (and so many others) need take a more considered approach to understanding immigration.

I read that your mother was an intellectual.

I think she would be, by far, my greatest influence when it came to a love of the arts and humanities. I don’t remember my mother without a book in her hand. She was always reading. And she always encouraged me to not only read but to read fairly difficult things at an early age. I remember reading Sartre and Camus, Searle and Heidegger—the fathers of existentialism—in high school, and discussing it with her. She always had small get-togethers at our house in Colombia with artists and writ- ers. She’d take us to museums, theater, and movies. That started me loving the arts. I remember looking at art books very early on, just the pictures, and then, when I went to college, I really missed that. In my dorm, whenever I would win a poker game—and I used to play a lot of poker—I would go out and buy a lithograph. I still have some of these earliest purchases in the kitchen or someplace.

So poker started your art collection.

Yeah, poker gave me the means, because my parents didn’t have any money. I had a full scholarship to go to university. Any extra pur- chases were provided by work or by playing poker. I also became a bit of an entrepreneur. I once bought the remaining stuffed animals of a company that had gone bankrupt, filled vans with them, and went out during Valentine’s Day and Christmas and so forth, selling them at colleges in New York and Long Island. We’d sell these stuffed animals we’d bought for 50 cents for $5 or $6—they were still cheap. In poker, thankfully I was sort of successful.

Most importantly, I was able to afford to spend a year in Europe after university—this was Europe on $5 a day. I wasn’t going to hotels; I was staying in youth hostels and friends’ apartments in sleeping bags. These were experiences that one would never be able to duplicate again. I travel very differently today. Art became important, and when I went to Europe, art became even more important. I remember, even though I had had a chance to go to great New York museums, in Europe every city had a museum. Every city was a museum. Cities and architecture [there] made me rethink about what I wanted to do.

You started your career helping to house the poor and elderly as a city planner in Miami. What was happening with your art collection?

My collection was very, very personal and Latin-centric. I was very proud of being Latin, and when I made the decision of staying in the United States, I didn’t want to lose those roots. I became a collector of all the great Latin American masters: Diego Rivera, Wifredo Lam, Joaquín Torres García, Rufino Tamayo, Carlos Rojas. It was a chance for me to continue to read about Latin America and what these people had done and were doing. This provided me a link to my roots.

Being that I’m in Miami, I always thought that Miami was going to be the capital of the Americas—it’s strategically located with a large Spanish-speaking population—and I always thought that the collection would become a part of a museum. I wanted it to be enjoyed by others, just like I enjoyed it, and to form the basis of a great collection. My hope still is that Miami and the PAMM will have the best Latin American art collection in the world. After the gift of all the classics I gave to the museum, we’re continuing to grow the collection. Most of everything I’m buying, if not to make our projects more beautiful, is going to my collection and the museum. Both my collection and the corporate collection will be going to the museum. In the long run, everything will be public.

What’s the difference between your personal collection and Related’s corporate collection?

The personal and corporate are very similar. The corporate changes in that many times there are pieces I haven’t decided will go to projects or to the museum—or museums; I’ve given to other museums, too. A lot depends on the needs we have and the needs of the museum.

When I buy art, I put it in three categories: 1) Art that’s clearly going to the jobs. For those works, we sit every month with our corporate curator [Patricia García-Vélez Hanna] and developers, look at the walls of all the buildings we’re planning, and say, “What do we want here?” Then we bring in the interior designers and tell them what we’re thinking, and they’ll give us their comments: “No, I would like Richard Serra instead,” for example. We buy everything from really expensive art to works that will go in secondary locations. I just finished buying a beautiful set of limited-edition lithographs by Richard Serra and another set by Alex Katz. We’ll buy lithographs that are less expensive than the originals to put in secondary locations, but always with the thought that the building is going to have great art. 2) Art that’s in a grey area that I call the “corporate collection.” These are pieces that I would like go to the museum—my thought is that they will—and we keep them in storage for that purpose. But if the museum says they don’t want a piece, or if after a month or so I go, “I don’t think that’s the right piece,” we’ll send it to a project. 3) Art that come hell or high water I want for me, that I want to see in my office—until the time I give it to the museum. These are works that are totally personal in nature. I buy them, even though I always ask questions, because they’re exactly what I want. These are what I’m going to look at day in and day out. They’re very personal decisions, as opposed to the others, which are for corporate projects. If I see a piece that’s strong either politically or sexually, it’s typically not something I’ll buy for a project, because the condo association will probably end up suing me, saying, “What the hell are you doing putting this here?”

Are you now looking to collect more young and emerging artists?

Absolutely, and many times we’re going back to who used to be emerging artists 50 years ago and are almost being rediscovered now. There are many examples, in Latin American art and elsewhere, in which you have somebody like this. Take Teresa Burga, who’s 80 years old. She was a Pop artist 50 years ago. She tells me, “I couldn’t sell this stuff for 5 cents! I can’t under- stand how the same thing I’m doing now was just not selling.” Then all of a sudden, at age 70, she was sort of rediscovered, and now it’s in all the museums. Rediscovering many of these contemporary artists who in many ways were ahead of their time and really good at what they did has been great. Another I’ve been collecting is the great American artist and photographer Barbara Kasten.

I just saw her exhibition,“Barbara Kasten: Stages,” at the Graham Foundation in Chicago [through Jan. 9, 2015].

Yes, and before that it was [at the Institute of Contemporary Art] in Philadelphia. This woman was a pioneer in abstract photography. She creates these incredible scenes. She’s a doll. I started buying her stuff like crazy. When I’d go to museums and mention Barbara Kasten, they’d say, “Who’s that?” Then all of a sudden—bam!—she was rediscovered. This evolution [of collecting and looking at art] has really opened a new way for me of looking at things. Through the eyes, the mind expands. Before, I’d go to a museum, look at things, and forget about them. I’d only look at impressionist art—Van Gogh and Monet, which were my favorites—and then with some of the other work, I’d go, “That’s weird.” Now I really try to understand the other work. Not that I don’t still love Van Gogh and Monet, but my tastes have changed. It’s like this with my 12-year-old son, Felipe: If you give him something that’s not a hamburger or a pizza, forget about it. But if you start forcing him to try other things, you see his tastes changing.

You recently started a program called Dialogues in Cuban Art. What was the impetus behind this, and how does it work?

Cuba’s opening up, and there’s a tremendous amount of great artists there. I thought that communication between the two countries was very important—and this is before Obama [called on Congress to lift the Cuba embargo]. Now I think it’s even more so. On the first Dialogues trip, we brought U.S. artists from Miami to Cuba for the Havana Biennale; the next one, we’re reversing, bringing Cuban artists to Miami, and they’ll be meeting with fellow artists here.

We’re doing the same thing with film. For the Miami Film Festival, we brought these Cuban cinematographers for these scholarships, to spend time here, go to the film festival, and present there. This year, we’re doing Argentinian films—we’re bringing the filmmakers here. One of the films [Wild Tales, directed by Damián Szifron] has been nominated for the Oscars for Best Foreign Film; we just had a big function for it at the film festival.

These things are extremely important as cultural bridges between the U.S. and Latin America. I look forward to Miami becoming more and more the capital of the Americas, where there’s continuous exchange. Miami is my city. I’m allowing people in Miami to view and participate in all these new cultural activities. One of the greatest thrills for me in the PAMM is the children. All third graders are taken to the museum for free with their teachers. Studies have shown that art, particularly at that very sensitive age, makes a child’s life not only scholastically better but better in general. We’re doing the same thing with the Mourning Family Foundation, which is taking kids from low-income neighborhoods to the museum after school. We want to bring the arts into that program and help them out.

Let’s talk about the connection between being a developer of buildings and a developer of culture. Where do you ultimately see the collision of the two?

I keep it together and I separate it. We think buildings are much better by incorporating art. From a marketing point of view, art is a great tool. Business and art mix very well.

I try to do the other art things separate from the business side. For example, people at the office will say, “Let’s do this with the art museum.” But I’ll say no. I don’t want it to ever be said that I’m using the museum, the Mourning Family Foundation, or something like that to promote my own economic goals. I don’t need it. I don’t want it. When I put my museum hat on and go to the board, Related as a company does not get involved at all.

But I’m sure it comes up fairly often. How do you deal with it?

I cut it. I say no. But if Related wants to do a great exhibition, absolutely—we have a fund in the company to do this. Two percent of our profits go to a Related foundation, to be used for philanthropy. We make the corporate decisions as to where that money goes. A lot goes to the arts, some to the homeless, some to cancer research. But that’s the philanthropic side of the company. We don’t want to use the museum to promote any one of our jobs, unless it’s some- thing that would be spectacularly good for the museum. If someone came to us and said they would like to do something for the museum and were going to give X amount of money, then we’d go to the museum. But we’re always extremely clear about everything, because I don’t want that association: “Is there any way he’s using this to further his business goals?” Not only is it wrong, I don’t need it.

It’s interesting how personal the company is—and the art collection is—yet you’re able to somehow keep this dividing line.

It’s an evolution. The museum has huge needs. It needs a better collection. We’ll continue to contribute to that. Plus, remember, while it’s very important for a museum to have a great collec- tion, it’s just as important—if not more—for a museum to have great exhibitions. When I go to Paris or New York, we don’t say, “Let’s go to MoMA.” The first thing we do is go to the concierge and ask what shows are going on, and ask the people we know what we should see. Based on that, we typically go do our art tour of the city. Miami needs to have those exhibits so that whenever tourists come here, they say, “What’s at the PAMM?”

It’s not only important that we give art to the museum but that there’s also sufficient funding in the museum budget to be able to create exhibits that are going to be successful. And successful has two meanings: 1) Is it art that’s critically acclaimed? 2) Is it a blockbuster? Is this something people will actually want to come see? I think it’s very important for museums to always keep those things in mind. You don’t want to do critically acclaimed exhibits that are so far out there that nobody wants to come see them. At the same time, you don’t want to do things that are so popular that they’re just not interesting or artistically good.

In addition to your work with the museum, you’ve installed a lot of public sculptures throughout the city. How do you hope your work as a patron can bring more art to the public?

We have a major Fernando Botero torso on South Miami Avenue; we’ve got two huge sculptures on Brickell Avenue in front of a building we own that we’re going to demolish. We’re doing the Jaume Plensa sculpture, which after Chicago will be shown at the museum until the building’s done. We want as many people as possible to see the artworks.

Is most of your focus now on the museum?

My biggest focus is on Miami becoming a world-class city. Everything that leads to that is very important to me. We’re talking now about a museum park. There’s no great city that doesn’t have a central park, whether you go to Paris, London, New York, Chicago, or Sydney. Miami doesn’t have that, and we definitely need it. Transportation, employment, and all the things that are going to contribute to making Miami a better place are very important to me. I’m very involved with FIU, the University of Miami, and Miami-Dade College. The building for the architecture program at the University of Miami is the Jorge M. Pérez Architecture Center, and I’m on the university’s board. My concentration is on Miami. It has so many needs as a young city. It’s consuming. And we don’t have the Coca-Colas, the Googles, or the IBMs here—the corporations that can say, “Here’s $100 million. Go do it.”

We’re a city of a lot of smaller entrepreneurs. We just have to make the continuous effort to catch up to those cities with hundreds of years on us and a lot of money—and a tradition of giving. We need A) to create the wealth here in Miami and B) to serve as an example for others whenever we give. This is why I joined the Giving Pledge. I was the first Hispanic to do so, and I still might be the only one. When you get to a point of having more money than you need, it’s very important to separate what you want to give to your family and what you want to give back to society. I think the Giving Pledge is good: You give half or more of your net worth to philanthropy, and you get to pick where you want it to go. While I give to other places outside of Miami—my wife, Darlene, and I just did a big cancer research grant for the Massachusetts General Hospital at Harvard; I got sick one time and they were amazing—the majority are for making Miami great.

You were talking about a lot of social issues having to do with Miami. Do you look to art as a way of exploring, say, homelessness or rising sea levels?

Sometimes—I don’t know how art can deal with rising sea levels. But yes. We’re talking to Baptist Hospital, maybe the largest in the Southeast. It’s been shown that cancer patients exposed to art do better. When you can combine the arts with ways of making people better—which can be anything: at-risk youth being exposed to it, creating programs for the elderly—it’s a good thing.

Have you ever been healed by art?

Well, art changes my mood. When I’m in a bad mood, I go to a museum and come out happy. The biggest example is I went through this fairly serious disease. It’s now 100 percent taken care of, but it was a humongous operation. I couldn’t move for six weeks. The first thing I did in a wheelchair—in the winter in Massachusetts, which was freezing—was to go to a museum. My wife took me. They had a driver, put me in a van, took me there, and rolled me out. It was amazing. I felt like shit—first in a hospital, then in a hotel room with all these tubes. But then I went out. Going to that museum took my mind away from things. That’s the value of the arts. While being treated for cancer, it’s great to experience something like this. So yes, I think the arts have a very health-related component. I guess that’s my biggest experience with it: as something that was very meaningful when times were grim.

It must keep you grounded, too. I can only imagine all the shit you must deal with day to day, but you always have your art collection.

Yeah! To me, though, it’s sort of different. I change out the artworks almost every day. If you come here a month from now, something in this office will be different. I hope that for others art is just a little percentage of what it means to me. It’ll make their lives better.

Art at its best can reverberate and cross borders.

Right. One of the things we go through as politicians—with my hat on as the head of Miami’s Cultural Affairs Council—is the huge multiplier effect that the arts have on the economy. From performing arts to museums, people go out and spend a lot of money. This is a huge economic indicator, which many times for pol- iticians is particularly important. It allows them to say, “We’re creating jobs. We’re making the economy stronger through the arts.” Look at what Art Basel has done for Miami: It’s not just because it’s a fair that a bunch of people come to; it puts us on the map as a cultural center. With more museums on the way—the [Patricia and Phillip Frost Museum of Science] is now being finished—we’ll be even more on the map. People who come here will say, “Wow, Miami’s not just a place for sun and great discos at night.” They’re gonna see that during the day there are all these cultural things to do. That’s what I’m trying to bring about with the arts and with everything else I do.