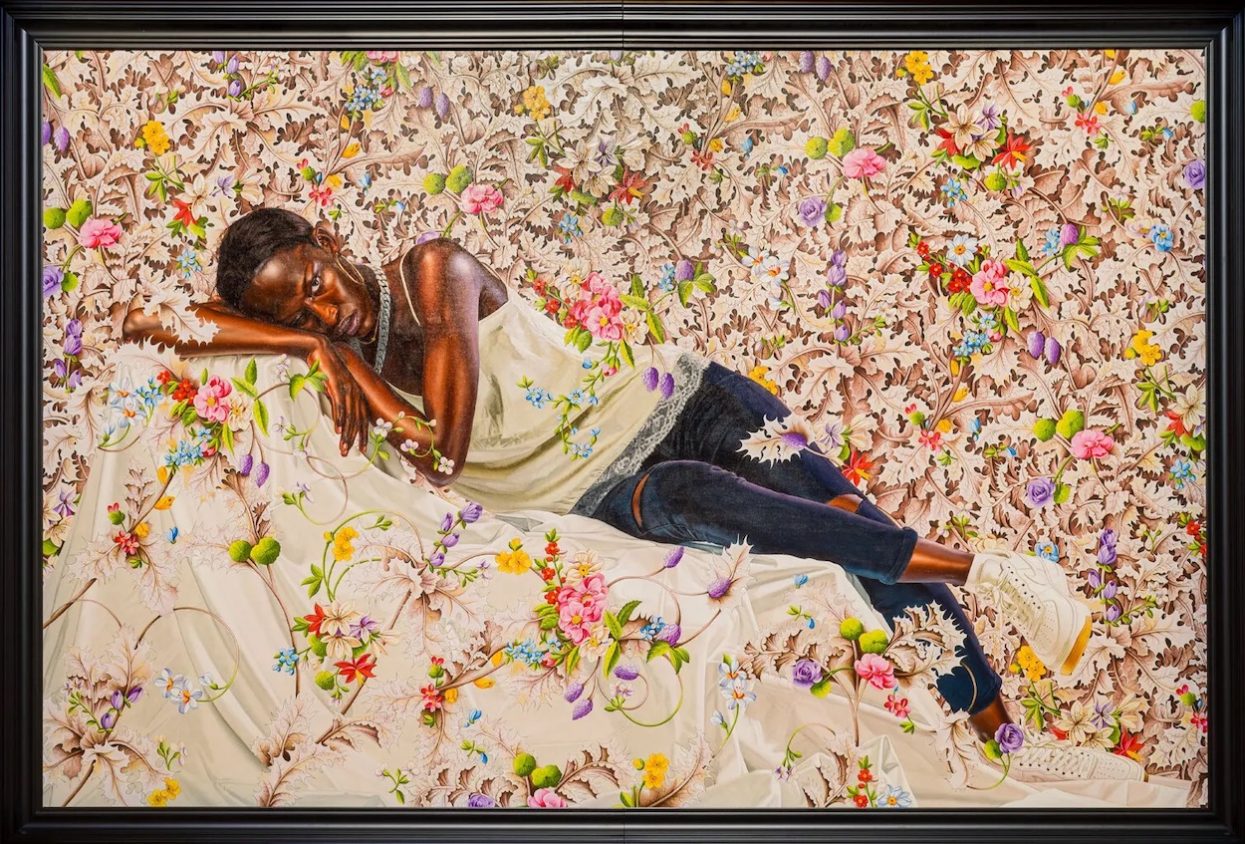

Touching fine art is forbidden at most institutions, but visitors to this past year’s Venice Biennale were so moved by Kehinde Wiley’s billboard-size paintings and giant sculptures of Black people in crumpled, supine positions that many wept, reaching out to grasp their hands. Wiley completed each of the show’s 25 artworks against the backdrop of the George Floyd killing and Black Lives Matter uprising. In Wiley’s paintings, he illustrates Black people in vibrant, lavish settings that reference religious and mythological Western paintings. In this series, however, each figure is struck down, wounded, resting, or dead.

The exhibition, called “The Archaeology of Silence” and organized by Musée d’Orsay, recently opened in the United States for the first time at San Francisco’s de Young Museum, in close proximity to neighboring Oakland where the Black Panther Party was formed in the 1960s. Given the harrowing nature of the work, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (a nonprofit comprising both the de Young and the Legion of Honor) is anticipating an emotionally charged response. To ensure the pieces don’t overwhelm visitors, the museum created a “respite room” where they can pause and regain their composure as they absorb the message.

Wiley requested a direct spotlight illuminating the works, which otherwise sit in a darkened gallery. Some may read the presentation as meditative and celebratory; others, as ghostly. “The nuances of the hair-braiding style and nails and phone technology—it’s making it violently present right now,” Wiley tells the New York Times about each artwork’s details. “You start to piece together a story based on your own baggage. That’s the through line throughout all of it—these bodies chopped down.”

Other institutions are following suit. When a major survey of Philip Guston works landed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, this past year, it handed out statements from a trauma specialist—a “content warning” in internet parlance—alerting visitors to upsetting work ahead. (Guston pivoted from painting abstractions to cartoonish figures donning Ku Klux Klan hoods in 1970.) Likewise, the show’s outing at the National Gallery of Art in Washington was designed so visitors can bypass unsettling pieces. “Today, we have an expanded notion of harm,” says Tom Eccles, executive director of Bard College’s Center for Curatorial Studies. “No museum wants to be in the business of creating a context of harm.”

“Kehinde Wiley: An Archaeology of Silence” will be on view at the de Young Museum (50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Dr, San Francisco) until Oct. 15, 2023.