Few human attributes reflect an era’s general mood—or serve as a vehicle for self-expression—better than hair. Take the ornamental styles of late-18th-century women, the politically charged afros and skinheads that emerged in the 1970s, and the avant-garde quaffs found on fashion runways. Each is examined in “Des Cheveux et des Poils” (“Hair and Hairs”), an exhibition on view through Sept. 17 at Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Collecting close to 600 works, the show investigates how hairdos form an essential aspect of identity.

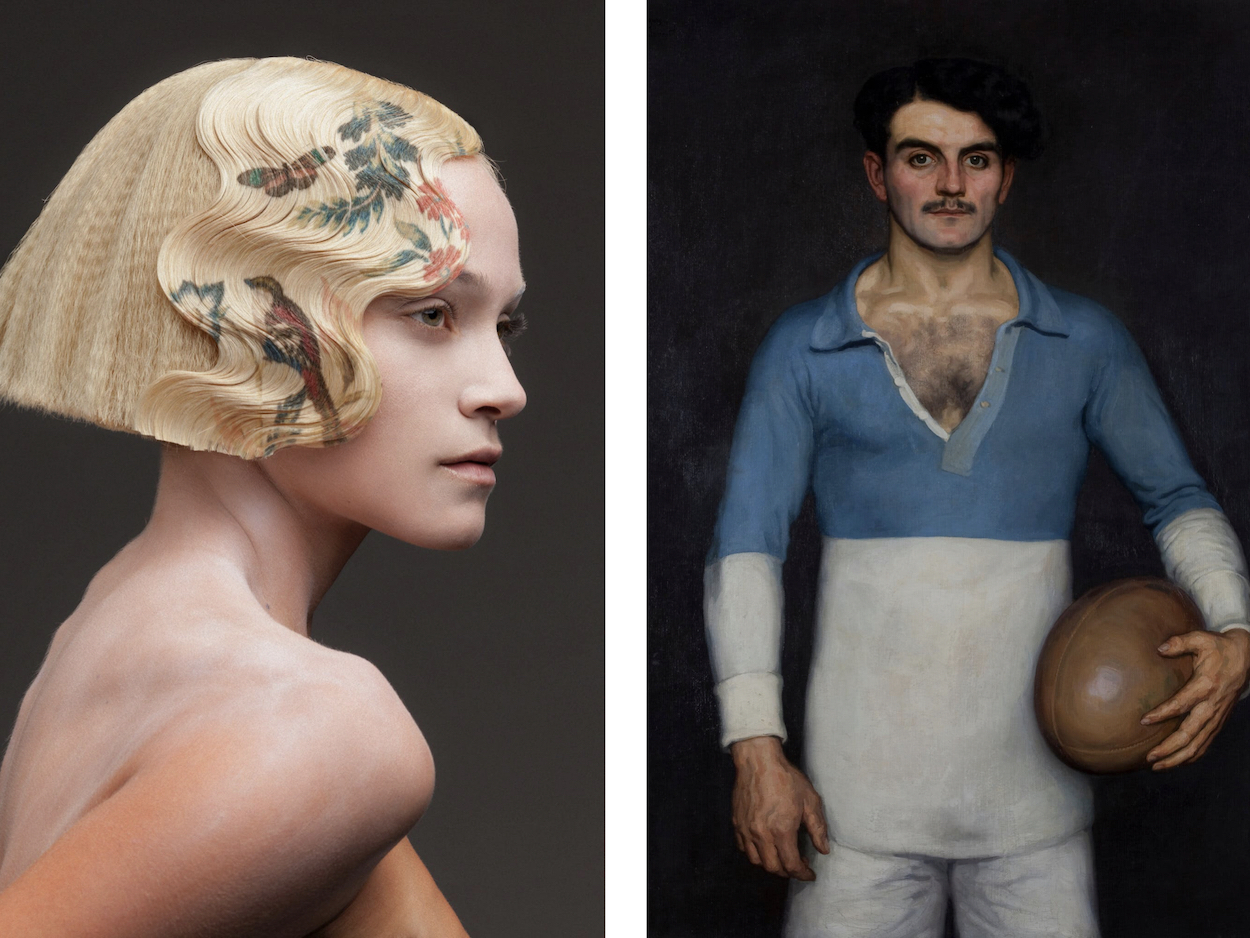

The show stretches back to the 15th century, when female styles proved to be a major social indicator. Women wore veils to obey the command of Saint Paul, but gradually abandoned the practice in favor of extravagant compositions like 18th-century poufs and hurluberlus—or, depending on one’s social class, taut Victorian austerity. (Well-to-do women rarely appeared in public with their hair down.) Ditto for men’s facial hair, which was rare until the 16th century when a handful of Western monarchs sported beards, sparking a cyclical fervor for mustaches and sideburns that persists today. Body hair, meanwhile, was long viewed as taboo. Nudes in visual arts often excluded hair, depicting smooth, hairless bodies as aspirational.

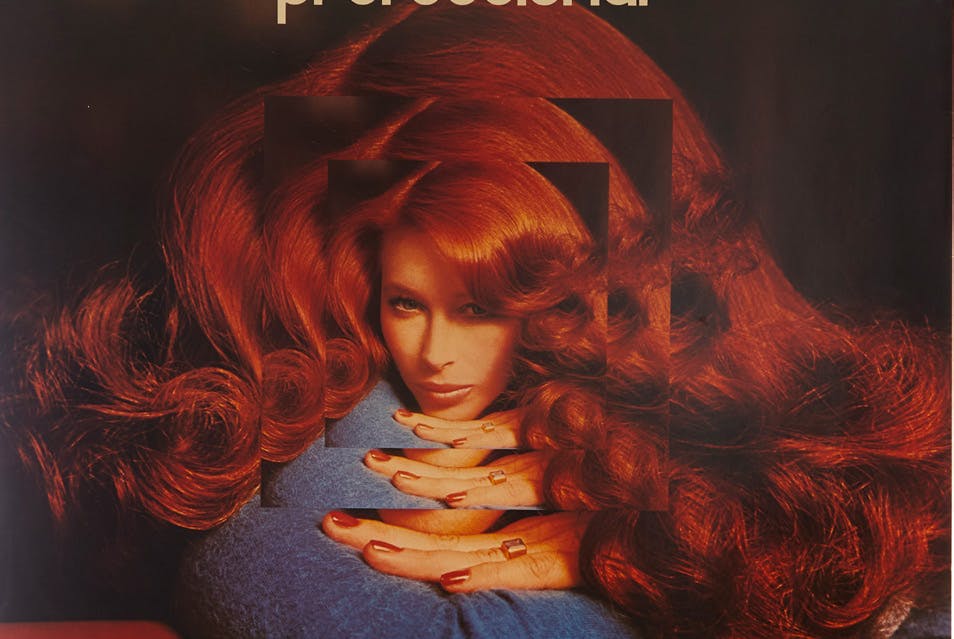

Encapsulating hair’s multifaceted history in a mere 600 objects is no small feat, and the exhibition finds an abundance of thorny topics to unpack. Among them: the implications of baldness, the popularity of wigs ranging from King Louis XIV to Andy Warhol, and the symbolism of natural colors such as blonde (childhood innocence) and red (sultry witches). “An exhibition about hair,” the critic Rosa Lyster writes for the New York Times, “is also an exhibition about self-presentation, self-perception, difference and hierarchy, race, religion, control, disgust, childhood, adulthood, masculinity, and femininity.” But in the interest of not splitting hairs, the regal chignons and gravity-defying curls are entertainment enough.