Neighborhood rebranding can be contentious. It’s often seen as a bellwether of gentrification: everyone from big tech to real-estate developers have gotten side-eye for abruptly renaming longstanding enclaves in a corporatized image that best serves their commercial interests. Local governments can, and often do, join residents in refusing to use increasingly bewildering names that seem to have been spit out by chatbots. ProCro, Rambo, and BaCoCa are a handful of real-world examples of the phenomenon that’s been parodied by It’s Always Sunny and even Tina Fey’s Baby Mama. But for Sun Valley, which the Denver Housing Authority calls the city’s “poorest neighborhood,” a $240 million redevelopment will see the community retain its name and deploy a shiny rebrand as part of a revitalization effort.

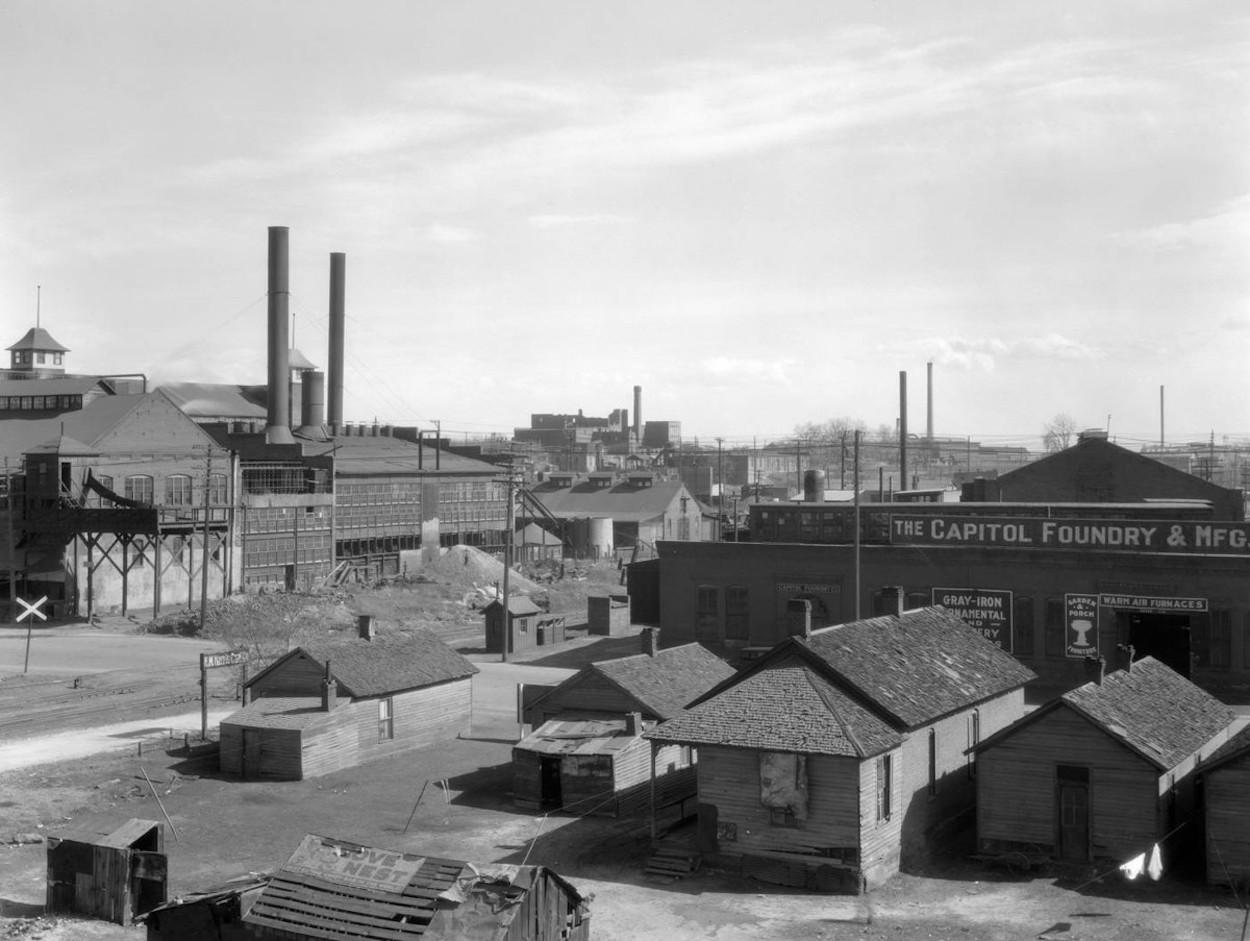

Sun Valley is home to Denver’s first public housing project. After the neighborhood was rezoned for industrial use in 1925, its residential blocks fell into disrepair before being transformed into public housing as part of the original New Deal. Rail lines, highways, and a sharp economic divide—more than 80 percent of residents live below the poverty line—separate Sun Valley from Denver proper. The housing authority set out to demolish the outdated infrastructure in 2010 to build a mix of new “subsidized and free-market housing.” Additional improvements include “a public park, a community garden, a community-operated supermarket, and a job training center,” all anchored by a new brand identity and wayfinding system developed by local studio Wunder Werkz.