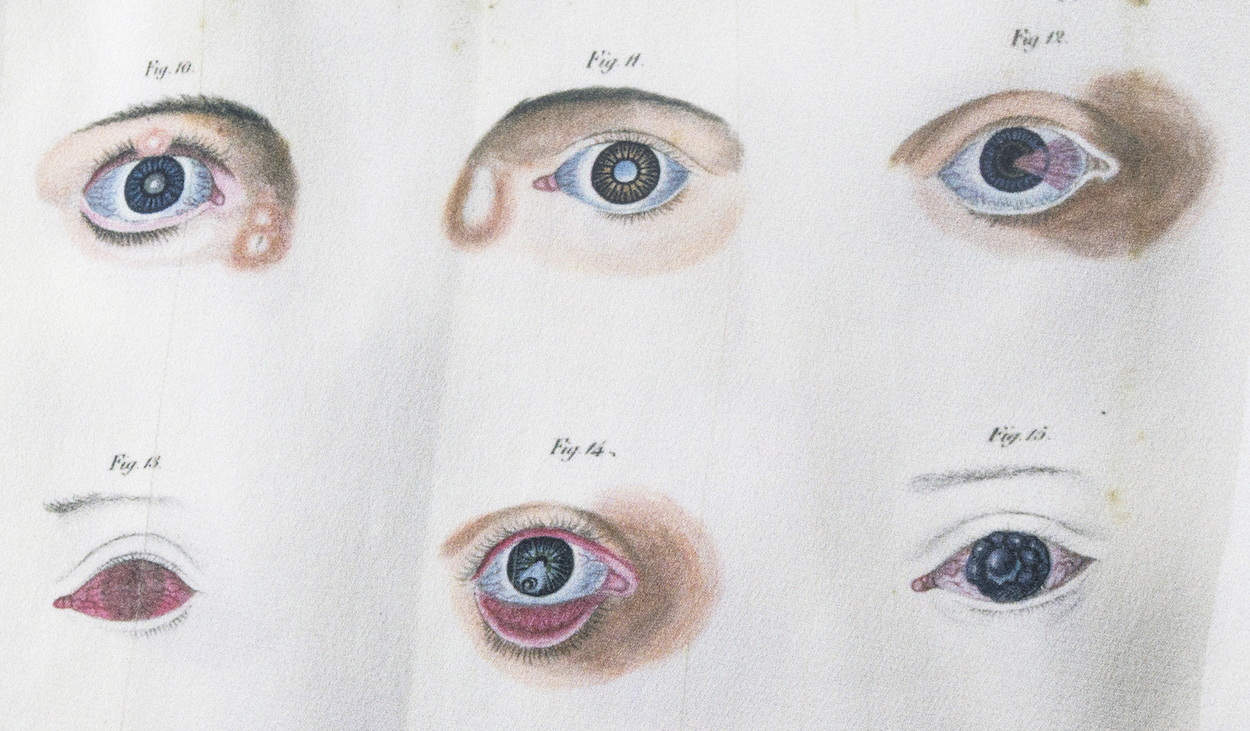

New York’s fashion scene, much like its neighborhoods, has succumbed to gentrification. Prim, ladylike archetypes have set up shop where suggestive, cosmopolitan style once reigned. On one end of the spectrum, contrarians like Shayne Oliver and the Vaquera quartet make bold, subversive statements, while former purveyors of urban sex appeal like Alexander Wang polish off their collections and move in the opposite direction. Firmly planted in between is Linder, the coed accessories and ready-to-wear label helmed by Sam Linder and Kirk Millar, who revel in unsettling, intriguing elegance. At face value, the designers appear to be stoking controversy with grotesque references, such as diseased eyes from a Victorian medical journal, and provocative details like fur manipulated to resemble body hair. In truth, they’re telegraphing their fascination with visuals most would find repulsive while championing a sexy, primal confidence that echoes New York’s unapologetically aggressive temperament. This spring, as Millar shifts his focus to the brand’s menswear line and Linder takes charge of womenswear for their upcoming fall collections, the duo sits down with Surface to discuss their often-misunderstood point of view.

Sam Linder and Kirk Millar Find Beauty in the Grotesque

The designers behind coed ready-to-wear label Linder delve into their attraction to the repulsive and taboo.

By Shyam Patel January 18, 2018

In your spring 2018 womenswear collection, graphic illustrations of diseased eyes from a 1834 ophthalmology manual by French physician Victor Stoeber are arranged like polka-dots on beautiful silk fabric. Was the motivation behind that to upset people?

Linder: Unconsciously, that’s probably true. It’s sad to see something scrubbed of defects and imperfection. Something very pretty, with no connection to something earthy, can feel lifeless.

The eye is also a symbol that can repel the evil eye. As two men doing womenswear, we always have to worry about the specter of the male gaze. On a subconscious level, this print is sort of deflecting the male gaze.

Millar: Seeing disease immediately puts people in a certain frame of mind. If we see somebody with a diseased eye and find it scary, we don’t like to acknowledge it. But the individual with that defect is still a person. So [the print] is not about upsetting people. We’re placing value on something others would push aside.

Does shock value resonate with your customers?

Linder: Our focus is on feeling fascinated by what we’re working on and less about what it’s going to mean to someone else—that should take care of itself. We’re always asking ourselves if what we do is interesting, or if we’re just flattering ourselves.

Millar: I think a lot of people work that way. They want to project that they’re the masters of a craft or aesthetic. In reality, preserving craft is a very conservative thing to do. You have to challenge yourself beyond that.

Speaking of challenging conventional ways of thinking, you’ve previously said your take on gender is to acknowledge the differences between the male and female body.

Millar: Men and women have masculine and feminine aspects to themselves. When we say “acknowledging the differences,” that doesn’t mean there’s no flexibility. It was a reaction to people saying we make gender-neutral clothing.

Linder: There’s no desire to force any kind of identification. We both feel masculine and feminine energies. We don’t want to erase the difference between those, but rather combine them in unexpected ways. No one is purely masculine or feminine. It’s just not how we’re made. I would be extremely bored and depressed if clothing evolved into a genderless norm and that polarity was erased.

You make it a point to highlight that polarity—by giving a female model an erection made of denim, for example.

Linder: There are a lot of ways to look at that denim codpiece. When they were currency, codpieces worn by men of a certain social status to express power, virility, and wealth. I was reflecting on phallic feminine energy and how it still scares people—even though society is trying to empower women through feminism.

Millar: Gender seems too big a topic to get your mind around, so we’re always playing with some aspect of it. We’re drawn toward whatever feels taboo. A woman with an erection is something that feels unfamiliar, so our desire is to go there.