At nearly 70, glassblower Simon Pearce has no reason to worry about his reputation. An Irishman who moved to Quechee, Vermont, in 1981, setting up shop in a former woolen mill, Pearce now has 284 employees who translate his Georgian-inspired designs into kitchen- and homewares. So when family friend Glenn Suokko, a photographer and writer, proposed a new book about Pearce, the designer initially needed some convincing before he relented. “Glenn is fantastic, and when he does something he does it so well and so beautifully, and it was a very painless exercise,” says Pearce.

Suokko had documented Pearce’s work for a 2009 book on his and his wife Pia’s lifestyle, centered around running a destination restaurant in tandem with his workshop, all housed in the mill. This would be a different story. Both Suokko and Pearce agreed that Simon Pearce: Design for Living (Rizzoli), published this fall, would illuminate Pearce’s design life, giving ample room to the profound influence of his parents’ lives and interests, the artists and designers who permeated Pearce’s childhood, and, of course, Ireland. “He has an incredibly innate sense and understanding of materials and form,” Suokko says. “That’s why his work is so amazing.”

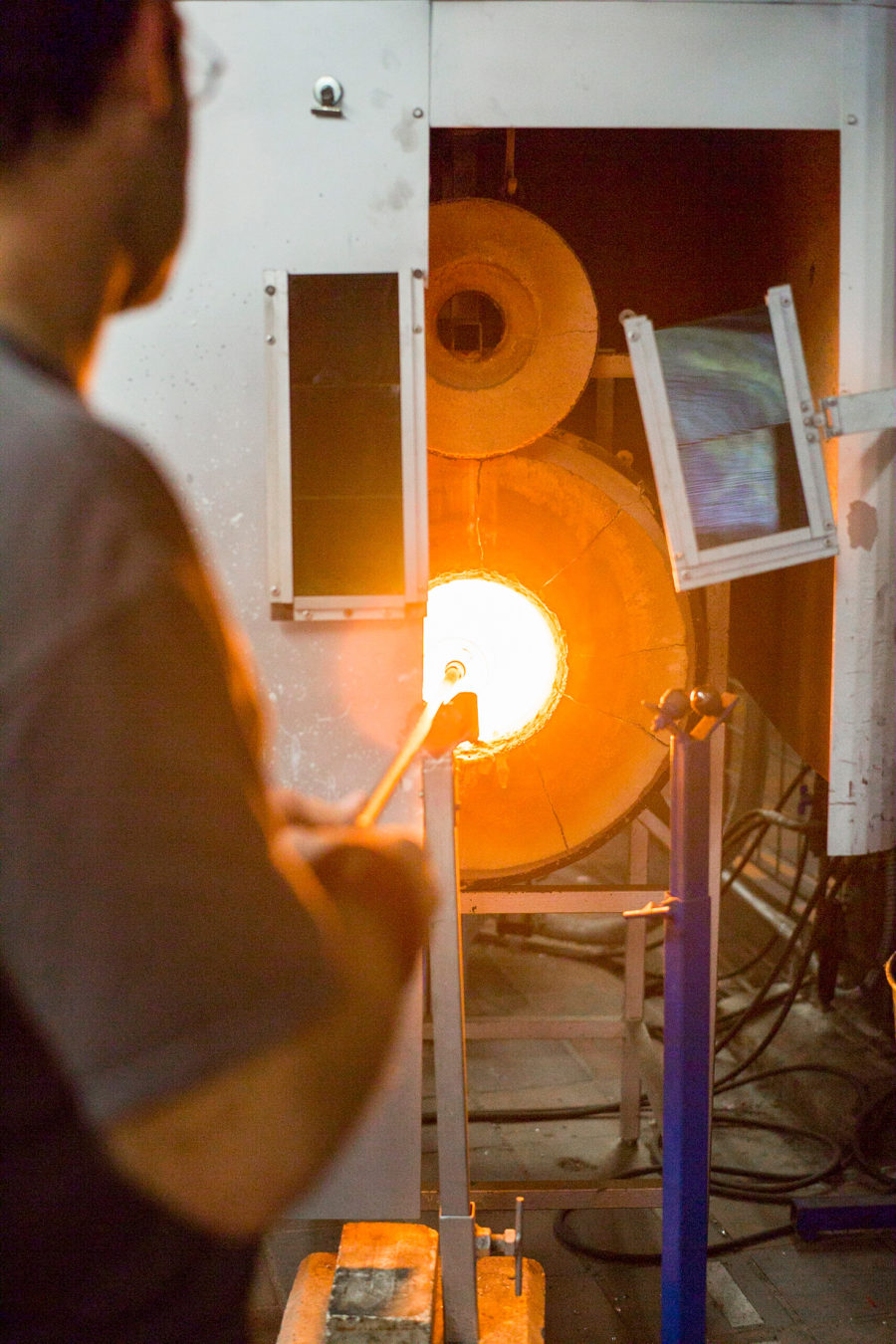

Pearce was born in 1946 in London, but at 4 years old he and his parents moved to Ireland. There, his father, Philip, built a house overlooking Ballycotton Bay and filled it with Scandinavian furniture and housewares as well as local pottery and crafts. Philip eventually established a pottery, and, at first, Pearce followed in his father’s footsteps. Pearce’s mother, Lucy, who had a sharp eye for design, helped grow the business. After mastering pottery, Pearce switched to glassmaking, in part due to his fascination with the collection of blown glass owned by his godfather, the painter Patrick Scott. Pearce went on to study with glassblowers around the world before establishing his own studio in the ’70s. As shrewd at business as he is attentive in his art, Pearce was frustrated by the bureaucracy and economic climate in Ireland, and moved to Vermont, a place with its own verdant beauty and “no roadblocks,” says Pearce.

Design for Living chronicles Pearce’s rich family history, illuminated through lush images of his homeland alongside glassware, mostly shot in Vermont. Suokko dedicated the final chapter to Philip Pearce’s pottery, shaped by his teacher, master Irish potter Willie Greene, and Bernard Leach, considered the father of British studio pottery. The legacy of Philip’s studio, inherited and now operated by Simon’s brother Stephen, lives on, too, in Simon’s craft.