We spoke with Fredi Devas, the producer and director of the “Cities” episode of BBC’s Planet Earth II, about the growing presence of urban areas around the world and how that’s impacting wildlife. Here’s a condensed excerpt of what he told us.

Concrete Jungles

Director and producer Fredi Devas answers our questions about Planet Earth II’s “Cities” episode.

Interview by Rachel Small April 03, 2017

What stands out in “Cities,” to me, is how it’s not a given, among the various circumstances presented in the episode, that animals are assimilated into their environment—because, of course, the environment is man-made. Where did the concept come from?

In all of the BBC landmark wildlife series, they haven’t before touched on the urban landscape as a habitat that can be suitable for animals. The background is, my father is an architect and I grew up with an interest in architecture. He’s also very into green architecture. For a 2013 BBC series called called Wild Arabia, I went to Masdar City, a planned urban development within Abu Dhabi. There, old architectural techniques were being used to help cool courtyards in modern buildings. In that film, we looked at how efficient buildings can be with relation to reducing carbon dioxide emissions. It makes it exciting to see, in cities, that greenery is being used on buildings.

What examples did you focus on?

One of the key collaborations was on with the Vertical Forest [dual residential towers in Milan that are lined with trees at each level]. What was brilliant about the architect, Stefano Boeri, and his team, was how passionate they were about this project. He was working alongside a botanist called Laura Gatti. She’s one of the best, if not the best, botanists in Italy. “When you plant a tree it can’t grow legs and walk away,” is what she says. You really have a duty to care, to plant it in conditions in which it can thrive. She cares enormously about the plants. And the architects are not thinking, “Well, we want dying trees on the sides of our buildings.” So, she tested the trees in wind tunnels, because if they’re going to be on top of a 30-story building, if branches break off, there could be a lot of damage.

How did you portray the Vertical Forest in the episode?

There’s a 12-second shot that shows the greenery—those trees and those bushes—growing over a two year period. We had two cameras in position on top of the tallest building in Italy at the time, facing the Vertical Forest. The same number of trees, in a [natural] forest, would take up 10 times the space. There were already birds nesting in the trees when we first went to film, and insects pollinating the cherry blossoms. It was great to see that resilience in the wildlife.

What about the developments you highlighted in Singapore?

Singapore is great, because it has this entire philosophy. It began in the 1960s, when the founding prime minister of modern Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, led Singapore to embrace becoming a “garden city”—a city within a garden. The emphasis is on green space. The government created an incentive so that, if any building is built over a green space, then it must incorporate as much, if not more, green than was built over—on the side of the building, on the rooftop, on the walls, on the inside walls, all of those areas. I think, at the heart of it, they recognize the many benefits to well-being that come with having an attractive city, and an attractive city often has a lot of greenery.

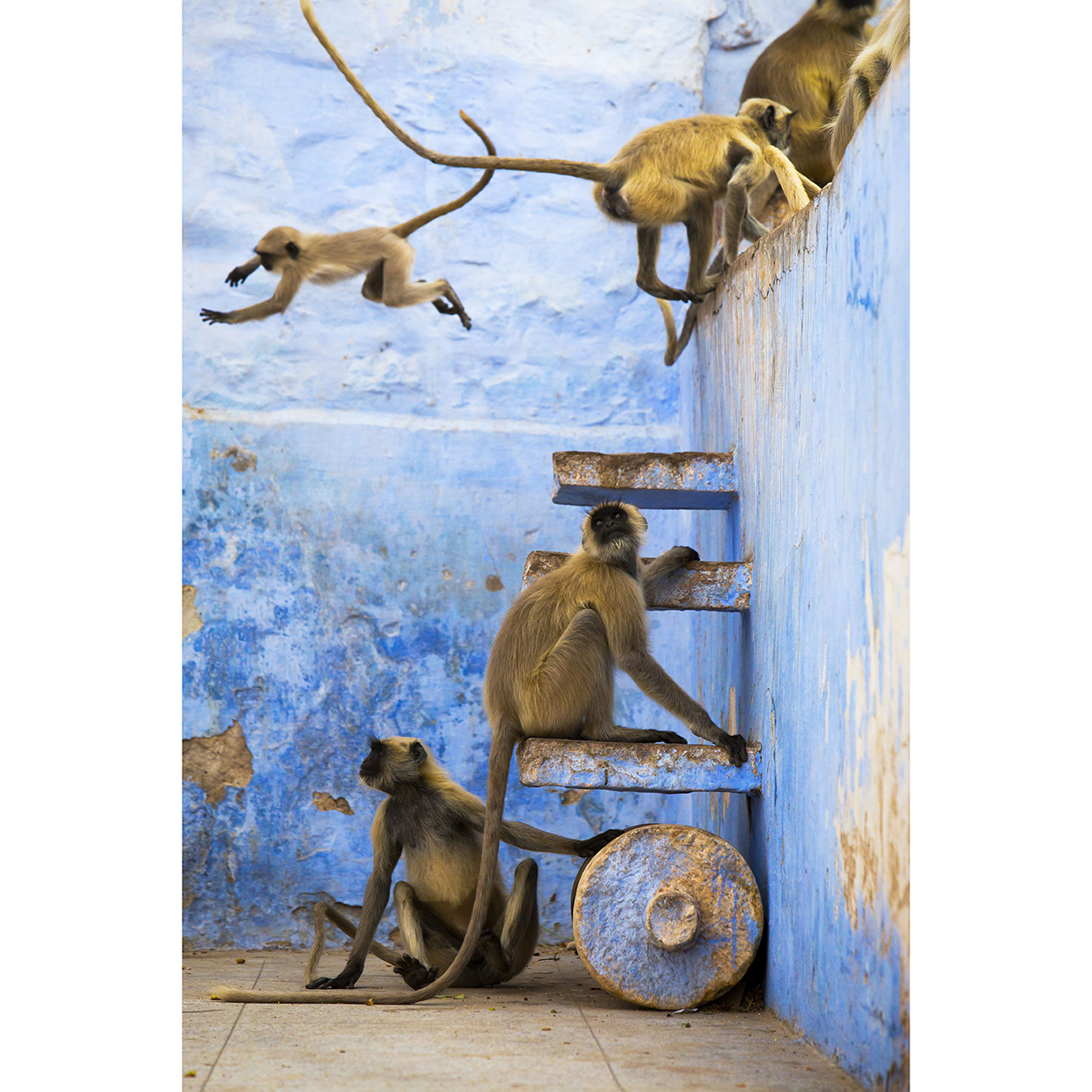

That’s very deliberately incorporating nature into a city, but I love how, in India, the two species of monkeys that you documented—the Hanuman langurs, in Jodhpur, and the rhesus macaques, in Jaipur—seemed to be thriving in rather dense urban areas.

That’s true. The Indian people are remarkably tolerant of the wildlife that shares their cities with them. You know, the langurs that we showed are revered because they’re associated with the Hindu god Lord Hanuman. The macaques are also associated with Lord Hanuman—although, they have a different character, stealing from the market. But some people feed the macaques as well, like the Jain people, who are break up bread crumbs to feed the animals. So many species are seen from within a spiritual context. The other example we show is the leopards in Mumbai, where nearly 200 people have been attacked in the last 25 years. Any other country in the world would probably dart those leopards and relocate them. Instead, the Indian people are saying, “No, this is a protected forested area within the city, and we’re going to try and learn from these attacks so leopards can live in proximity of humans.” That’s pretty inspirational.

You did your PhD on baboon behaviors. Based on your previous knowledge of primates, what struck you the most about the population of langurs in Jodhpur?

The generosity of the people towards them is extraordinary. If a langur dies in Jodhpur, it will likely have a funeral. The langur is taken, maybe washed and bathed, then a painted throne is build around it, flowers are hung around its neck and it’s carried through the streets, and musicians will come out and sing and chant and follow it. The precession may go on for a couple of hours. And then they’ll give it a funeral, as they would do for a human. That gives you an idea of just what it means to the Indian people to look after the animals within their city.

In one of the final sequences, we see turtle hatchlings on the beach in Barbados, who have confused the moonlight’s reflection on the ocean with the light pollution coming from inland, which leads them to near-certain death. Off-camera, were you able to intervene, and turn the baby turtles around?

Yes. All of the turtles that were filmed were collected and released into the sea. That’s not to say the problem doesn’t exist. We worked closely to a conservation organization called The Barbados Sea Turtle Project. They’ve got a handful of volunteers who work tirelessly through the night, patrolling the beaches to find those disoriented hatchlings and get them back to the sea. The thing is, they could do with more funding, more help and more support because humans and cities are the reason why these hatchlings are suffering and it was only right for us to get involved and change, to return the disoriented hatchlings to the sea. We would film the shots to document what was going on, and the conservationists [would say], “Okay, that’s enough time now, we should really get them back to the sea.” We were very careful get the shots we needed and release them to the sea straight away.

What do you hope that people take away from the episode?

I hope, in the next decade, we see this trend, and we see policy change, whereby many more roofs and walls of our buildings are greened. There are so many economic, social, and health benefits to greening the cities. And, ultimately, I believe that maintaining a connection to nature is important for the human psyche. Now that more than half of us live in urban environments, it’s more important than ever to try and maintain that proximity to nature, within cities. That’s what I hope people feel inspired to do after watching the episode, is to think, well how can they green their city? What can they do to welcome wildlife back in?

The special collector’s edition of Planet Earth II is available now on 4K UHD, Blu-ray, and DVD in the United States and Canada.

(Photos: Fredi Devas/Copyright BBC NHU 2016)