Please note: This story contains explicit images and video content—of virtual humans. You may want to read it later, if you’re at the office.

NSFW: This VR Company Is Designing a New Reality Populated With Porn Stars

Welcome to Camastura VR’s strange new vision of sex in the 21st century.

By Gustavo Turner March 28, 2018“Go ahead, poke one of her breasts,” the voice tells me. I’m standing in a dark space lit by candles arranged haphazardly all over the floor. Right in front of me, the adult performer Casey Calvert is completely nude and gyrating sensually, enticing me to come toward her. I take the voice’s advice and poke Calvert’s right breast and watch her flesh dimple. She continues her tantalizing invitations, seemingly unaffected by this invasion into her body.

I remove the high-end virtual reality headset I’m wearing, and just like that I’m back at the Hard Rock Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. It’s January and downstairs the porn industry is holding its biggest annual event, the four-day AVN Adult Entertainment Expo (AEE). Floors above the convention halls teeming with fans clamoring for the attention of their favorite adult performers, I’m in a private suite demoing a new product by a recently incorporated company called Camasutra VR.

I slide my headset back on and am transported to a “cool downtown apartment,” a version of those generically aspirational properties that have mushroomed all over Downtown Los Angeles and Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I’m given handheld video game controllers and instructed to move around the young-professional bachelor pad, which has, for some reason, a stripper’s pole in the living room. The Casey Calvert avatar is here, too, doing another sensual dance. “Throw some money at her,” I am encouraged off-headset. I pick up a “money gun,” a bright-red pistol with a flat-shaped cannon that shoots virtual $100 bills. I make it rain for a couple of seconds, then move on.

There might be no better place than the AVN porn convention—which doubles as the sex industry’s very own CES—to explore the cutting edge of today’s tech-mediated experiences. Sensational notions of “future sex” might include hyper-realistic sex dolls with skin that warms to the touch or vibrators that are hooked up to the Internet of Things, but it’s virtual reality that has been heralded by adult-industry forecasters as both the unavoidable future of porn and the realization of long-standing sci-fi fantasies about sex. Unlike these other accessories-based advances, virtual reality has the potential to be the industry’s real game changer: It promises to go directly to the core of experience design and immersion.

The old adage that pornography is the first test ground for the survival of all new technologies—from the printing press to home video to internet file-sharing and streaming—seems particularly relevant for virtual reality; Camasutra VR, the latest flavor-du-jour (last October, The New York Times called the enterprise “a big player” in the world of “naughty virtual reality”), is just one of many companies experimenting in the space generally referred to as “VR Porn.” This catchall term includes producers of VR clips with live actors, businesses providing VR solutions for performers livestreaming (or “camming”) from their homes, and “adult playgrounds” like Red Light Center, an erotic massively multi-user online game/environment (MMO).

While a number of companies have been producing adult content for the variety of VR headgears on the market, from the high-end Oculus and Vive to the very inexpensive “cardboards” (simple holders for smartphones), there is currently a clear distinction between two types of VR pornographers: Those from the standard 2-D porn world who film VR scenes with popular adult performers, and those with backgrounds in visual effects and graphic manipulation who render sexified digital avatars the same way they create characters for video games like Call of Duty and Grand Theft Auto.

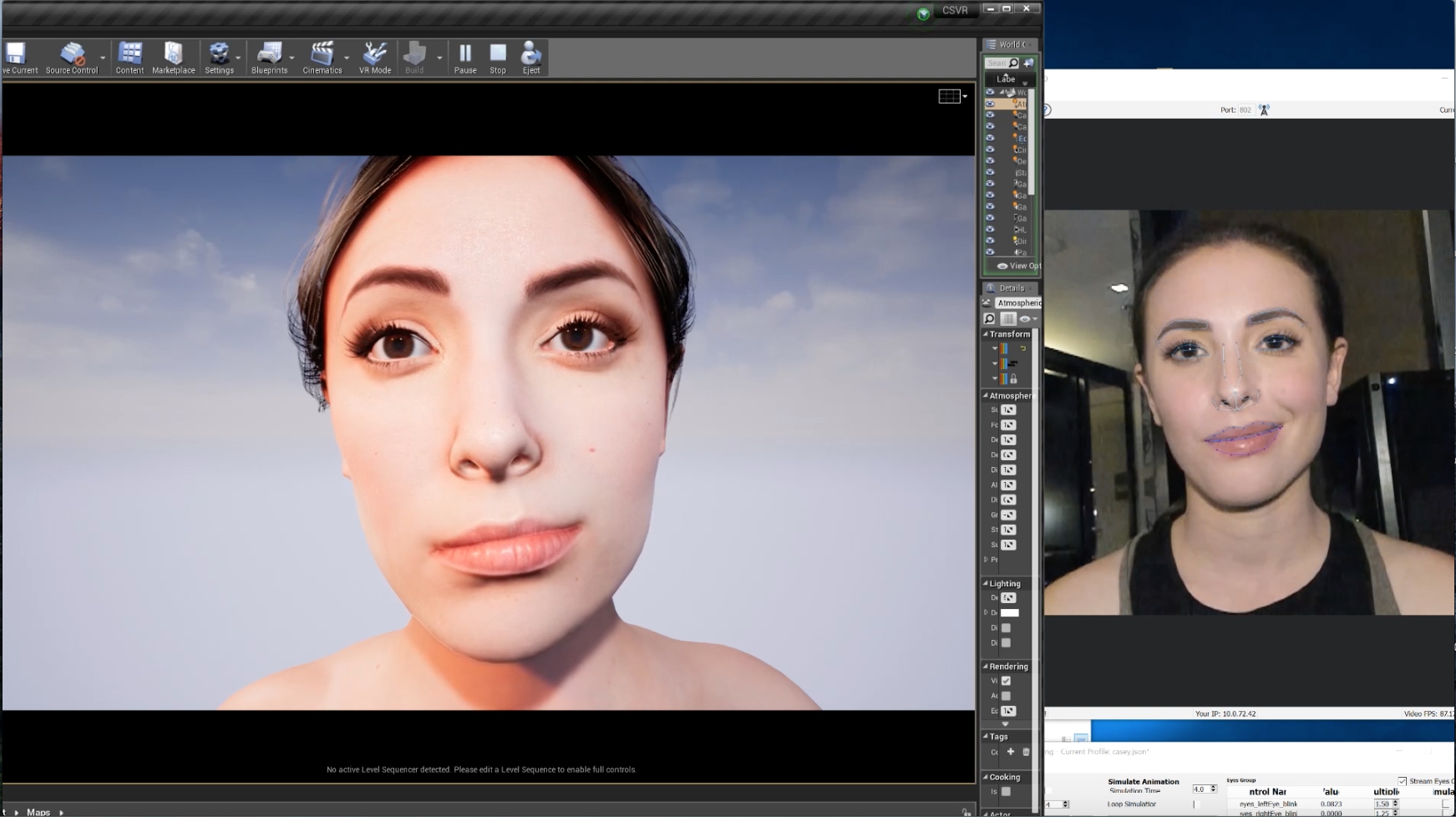

The Camasutra VR team belongs to the latter “rendering” camp, but their radical innovation is an attempt to combine—at the highest possible standard—the avatar-based aesthetic of gaming with full-body scans of actual adult performers. Hiring from the same talent pool that the rest of the porn industry uses, Camasutra VR pays them their regular day rate to be outfitted with motion-capture gear, placed inside a dome, and photographed by 142 cameras while striking a variety of positions and nearly 100 distinct facial expressions. This information is stitched into a full body scan, which Camasutra VR then uses to produce a digital avatar in the likeness of the porn performer.

While most of the other players in the VR porn space are focused on creating POV experiences in which a porn actress “services” the person wearing the headgear, or 3-D camming environments where the viewer at home can feel he (or she, but usually a he) is in the room with the cam girl (or boy, but usually a girl), Camasutra VR is busy trying to create convincing virtual copies of performers like the gyrating Casey Calvert who tried to seduce me in the simulation at the Hard Rock. And with them, they’re planning to populate a yet-to-be-unveiled, proprietary virtual world. Or as Camasutra VR’s website simply, and proudly, proclaims: “We’re building digital versions of hundreds of porn stars that are available for all your little fantasies.”

Of the several VR companies to have set up their booths at AVN this year, Camasutra VR’s was decidedly the most popular. Anticipation was high because creative director Adam Sutra had been teasing the unveiling of his unprecedentedly detailed avatars for several months on social media.

Adam Sutra is, of course, a pseudonym. The company’s four main partners are all people with extensive backgrounds in mainstream entertainment and advertising, which they are willing to discuss only off-the-record. “We all continue working for ‘the big American brands,’” Sutra tells me, hinting at Silicon Valley outfits and Hollywood studios. “We don’t want to compromise our current status [with those brands] by using our real names for this project.”

At his booth, Sutra, a soft-spoken European man dressed in inconspicuous techie-casual, chatted about the future of VR with the fans trying out the demo. Besides giving potential investors and journalists a chance to preview the product, his other priority at the convention was to convince more adult stars to sell them a full workday of their time—typically priced at between $1,000 and $2,000, minus agent’s fees—in exchange for having a digital avatar created in their likeness. By the time of the demo unveiling at AVN, their roster included top female performers like Anikka Albrite, Casey Calvert, Lily Lane, Jynx Maze, Krissy Lynn, and Honey Gold. They also have scanned Honey Gold’s boyfriend, male performer Donny Sins.

Sutra’s pitch to the “talent” (the industry’s term for performers) was interesting, a cross between “be part of something new/revolutionary in the history of sex tech” and “preserve your current beauty in digital amber for the ages.” The company’s Instagram feed is full of strange pictures of actresses being fitted with the scanning gear accompanied by captions like “@caseycalvert becomes immortal in her 3-D avatar” and “Welcome to the future, @kryssylynnlove. You are now immortalized and will live forever in VR.”

One afternoon during a break from “fan service,” porn actors Honey Gold and Donny Sins, the young, career-minded real-life couple who were scanned separately and together by Sutra, drop by the booth. For them, it is the first time seeing the full demo with their avatars. They find it amusing and shocking at first to see other people dry humping, fully-clothed, their interactive images on the screen. The novelty becomes enhanced when the performers are invited to try on the headgear and interact with their own avatars.

“Oh, man—that scan took forever,” Sins recalls. “It was pretty extensive. They have to put all the equipment on you—same thing as modeling for a video game, except this time it’s your actual face, your body, and your name. You walk into a giant dome of Go Pro cameras and they want you to make every one of your facial expressions. Then Honey and I did a fake sex scene, and at some point we had to use a dummy head to pretend we were having oral sex.”

“It was a completely new experience,” adds Gold. “I didn’t necessarily know what I was getting into. The main guy [Adam Sutra] was explaining to me that they thought this was a very good market for them, and how they were going to create an air chamber pressure suit in the future where people would be totally immersed with our avatars. In the long run, while this technology is amazing, I’m not sure who they’d sell it to.”

“Gamers are a big target audience for us,” Sutra told me at his apartment in L.A.’s Silver Lake neighborhood a month after his AVN unveiling. “In essence we’re building a very high-end computer game. We’re also allowing people to build in this world and partake [of it]. I think that will definitely appeal to gamers, and also to technology freaks.”

Back at the AVN booth, a woman finishes watching the demo and removes her headgear. She’s laughing with her friends about what went on when she recognizes Donny Sins, who has just pleasured her in the virtual environment. “Oh, that was you!” she says.

Sins has just watched the whole scene with the rest of the people surrounding the booth. “It’s kind of funny seeing myself—seeing the avatar—in action,” he says.

There are practical reasons why the very accomplished mainstream VR professionals behind Camasutra VR are devoting so much time to this side project. “Porn has always been a great research field,” says Sutra. “For VR, it’s even more ideal. See, when you’re designing characters for a video game, you have ‘cheats.’ You can spend all your time on the visible parts—the head, the face, the hands—but the rest is covered in clothes, which are easier to render. The biggest technical challenge is still the entire human body. The porn industry is ideal to perfect this technology and then take it mainstream.” After all, the performers are used to being fully naked and have no problem mimicking an enormous range of expressions that other models might find embarrassing or too intimate.

But finding well-known talent that’s professionally comfortable, quite literally, in their own skin, and turning them into a cluster of shareable and modifiable data, is just the first step of the Camasutra VR operation.

“One of the advantages of our content is that it’s platform-agnostic,” Sutra says. “Once we have this asset—the human scan, which can be reformed into a virtual ‘puppet’ or avatar—we can do anything with it.” It can be deployed in VR environments (like a video game), IRL environments as 3D-printed figurines, or in augmented reality, via a smartphone.

To demo the latter, Sutra pulls out his phone. He swipes a few commands and a version of Donny Sins’s puppet appears on the screen, humping obliviously into the room. “Now look,” says Sutra, getting more amused. He positions the Donny puppet, who keeps pumping, right next to where Camasutra VR’s chief financial officer John Donson is sitting. “He’s fucking your ear!” Sutra says. Then he starts resizing the puppet, making Sins really large, then small. Another finger swipe from Sutra and a miniature Casey Calvert appears underneath him. I’m watching the tiniest, strangest “live” sex show in a corner of a Hard Rock suite.

Through graphic manipulation, Camasutra VR can also merge various assets, like brand-name models, with other, more anonymous people. “We can superimpose Casey Calvert’s face on a really great pole dancer that we scanned,” Sutra says. “Casey is not really a dancer, so when we showed her the combined 3-D image she was floored.” “‘Oh my God—I can finally pole dance!’” Calvert screamed in delight, according to Sutra. “Making them new and interactive is the most difficult thing to do,” he said.

The technically minded Sutra does not mention other ways in which porn performers are ideal subjects for this inch-by-inch data harvesting. Most talent are not wealthy, and they live paycheck to paycheck, booking to booking. Their loose relationship with agents and managers (if they have them at all) makes it easier to convince them to part with their likeness rights for a one-time fee. And they have a devoted fan base (which they strenuously cultivate via constant social media engagement) that’s likely to purchase their avatars and figurines.

The objectifying “puppet” element of VR would seem less disturbing to adult performers, most of which had to engineer a separation between their “real selves” (birth name, personal life, family life) and their “porn persona” to deal with the still prevalent (and unfair) social stigma about sex work and sex workers. But in the case of the virtual avatars that Camasutra VR is creating, the objectification is not merely metaphorical.

Likeness rights have been a complex issue—feeding a cottage industry of trademark, copyright, and estate lawyers—since the 1990s, when we all realized that Humphrey Bogart, Elvis, and Marilyn could be “re-created” and “brought back to life” to be inserted in modern entertainment. This was way before that notorious Tupac hologram surfaced at Coachella and long before the brouhaha caused by Justin Timberlake’s thwarted attempt to resuscitate an unwilling Prince (“that’s the most demonic thing imaginable,” quoth the Purple One from the grave) for this year’s Super Bowl halftime show.

Plus, it’s not like porn performers are not already accustomed to many other ways of “selling their bodies” for money. Many adult actors and actresses have partnerships with realistic doll companies that make life-size sex toys in their likeness. Another lucrative sideline is what the industry calls “strokers” or “masturbators,” a whole range of smaller devices molded after specific body parts: penises, vaginas, anuses, heads, lips, hips, torsos, and even feet.

But do the sex workers being drafted for these brave new VR experiments fully understand the ontological difference between casting a mold of your genitals for plastic replicas and having all of your body and individual expressions turned into data that can be reassembled as a controllable digital puppet, possibly for eternity?

When I asked Sins if he knew whether Camasutra VR had secured lifetime rights to his virtual likeness, or whether he could legally do a competing full-body scan with a different company, or whether he would get residuals for all the futuristic uses his avatar might be put through, he said none of those issues had been discussed the day he was scanned.

“Frankly, I wasn’t really worried about likeness rights,” he tells me. “It was just another day, another booking, another shoot for me.”

Gold agreed. But after a few minutes of talking about it, she grew quiet and shared a series of deep emotional responses.

“When I saw the Camasutra demo at their AVN booth, it was fun at first to see myself up on the screen and see the fans interacting with my avatar,” she says. “But then I realized that they had given me a haircut that I haven’t had in a long time. And I was styled all wrong. I realized I had no control with how they were presenting me. I mean, that’s not my brand now. At all. I had no say how my avatar looked. They’re selling an image of how I looked before, not now.”

And then she saw the avatar of her IRL boyfriend, Donny Sins, having sex not with her—as she had experienced inside the camera sphere the day of the scanning—but with the Casey Calvert avatar.

“I didn’t know Donny could be paired with Casey Calvert,” Gold said. “I don’t really know her! That made me upset. None of this was pre-approved, I think. I was under the impression that Donny was going to be in a scene with me. That’s how we shot it that day.”

An essential human feeling—jealousy—had surprised her. Though by now she’s used to knowing that her boyfriend regularly performs with other female talent in the context of a professional porn set, this violation of trust (and possibly consent) upset her. The more she thought about it, the more the thorny issues around VR started spawning disturbing thoughts.

I tell her that Sutra had mentioned selling their scan information to fans with 3-D printers so they can make their own Honey Gold and Donny Sins figurines, like the ones Camasutra VR proudly displayed at its AVN booth.

“Figurines? That wasn’t explained to me,” she said. “Will we get paid for those sales? I need to go back and ask them.” These were very real implications of becoming a marketable avatar owned and controlled by someone else.

“And what if my avatar is doing anal before I do!” the professionally driven Gold blurted out, partially bemused, partially terrified. “That’s taking value from my career. I’m competing with my avatar! Oh, this is weird.”

I asked her if she had looked carefully at the Camasutra VR contract the day of the scan, if it had been different from other porn shoot contracts, or if she had noticed anything about likeness rights, or a timeframe, or conditions for the use of her “puppet” by the company. Had they surrendered lifetime likeness rights for a single paycheck? Could they freely resell their avatar to a different scanning company? Or would Adam Sutra and his team claim exclusivity out of that extremely expensive, eight-hour-workday day posing, emoting, and simulating several types of intercourse.

“I don’t think there was a contract,” Gold replied after a moment of silence and turned to her boyfriend and scene partner. “Donny—was there a contract?”

Neither of them was sure.

I did ask Sutra about contracts and the hairier issues around likeness rights when I spoke with him at his Silver Lake home. Were there any contracts? How were they different from standard modeling or porn video contracts? What happens when the IRL person changes hairstyles, ages, retires—or dies? This last issue was especially relevant around the time of the 2018 AVN Awards, which became a kind of pseudo-memorial to the late August Ames. The 23-year-old Ames had committed suicide a few weeks before the convention, one in a series of similar deaths of young women that moved the industry into a conversation about mental health issues. (Ames had been a high-profile poster girl for VR porn and likely would have been a prime candidate for one of CamasutraVR’s body scans.)

Turns out, Sutra, incredibly busy trying to build the perfect digital replica of the human body and working against the clock to launch his product and monetize his assets, had not had the time to delve into the strange new frontiers of likeness rights.

“It’s just like … the real world,” Sutra tells me, who shares the same lackadaisical attitude towards laissez-faire of the most confident technodeterminists. “You start governing when you come to certain actions. If people start doing things in the world that are obviously wrong, you’re gonna have to [say] ‘Ok, maybe we should change the rules of the world,’ right? [At this early stage] you can’t go and make these massive disclaimers before people enter and be like, ‘This isn’t allowed.’ You’re never gonna get something.”

“You do bring in a certain factor by opening it up to the people, because you never know what they’re gonna do,” he adds after fielding more of my questions. “I kind of like that kind of excitement, but there’s also some kind of fear for that. I’d imagine especially if you grow bigger as a company. We are tiny. We just wanna make cool stuff right now and hope everybody likes it.”

“That’s exactly the conversation that needs to be happening right now, not later!” Ela Darling tells me when I ask her about the avatar technology that Sutra is perfecting. Darling is known as much as an adult performer as she is as the VR evangelist in the porn community. Everyone, from cam girls looking for tips on how to enter the VR space (through her company, CAM4VR) to New York Times reporters looking for a reputable, quotable source for a mainstream article, eventually talks to Darling.

“I tried Camasutra,” Darling tells me, “and I thought it was pretty cool. Motion-capturing a performer’s body is pretty accepted, but as a performer, my first questions are: How are you going to compensate performers for giving up their image in a way you’re gonna be able to use? Is it in perpetuity? Are you renting it from them? Do they get royalties for it? Do they get royalties based on how many interactions they have?”

What Darling found most troubling was the lack of contracts and forethought. “I think Camasutra VR’s technology could be great for performers if they set up a strategy. If this is gonna be the new thing that will take over porn, how are you gonna justify the labor of these performers, who are the backbone of this industry?”

For all its state-of-the-art body-scanning and digital rendering, the technology hasn’t yet crossed the “Uncanny Valley”—the feeling of eeriness and slight nausea produced by a humanoid shape that is close enough to replicating a person, but quite not exact. It’s the reason why most people get warm and fuzzy about Mickey Mouse, but they get creeped out by the Tom Hanks–voiced conductor in The Polar Express. Still, it’s getting closer.

At this point, the clunkiness of the Camasutra VR avatars is somehow comforting. Their uncanniness tells us “we are not there yet”—there being the point when the rendered avatar will feel indistinguishable from a “meatspace” person, to use the derogatory VR term for physical reality. It’s natural to feel a sense of vertigo about the unfamiliar future that awaits us when VR achieves its goal of full “presence” and immersion. The vertigo confirms our humanity: We meatspace entities are entitled to feel anxiety about our future inadequacy or inability to adapt to the new world of mixed digital/physical.

Thinking about VR is important because it makes us reflect on the speed with which pre-21st-century notions of privacy have completely evaporated, on the feeling that we’ll be forced into an ongoing (and exhaustive) renegotiation of our rights as individuals, that we’ll have to redefine familiar ideas of personhood and self-fashioning. If a corporation offers us a little money (say, a couple of months’ rent or mortgage) for our likeness—which is tied to what used to be called “reputation” and has now become “our personal brand”—should we surrender control?

“That’s not the way we’re building [the model],” Sutra says. “Our idea is that our stars are going to puppeteer and use themselves. If Honey now is sitting at home and wants to do a chat show with a bunch of people in the virtual world, that’s all up to her. If she does that, then it generates revenue from her. The way I’m building it, the real exciting thing is gonna come when the actresses endorse their virtual avatar.”

“Retire early, put your avatar to work,” Sutra says. “That’s how I would approach it. If this is successful, and the girls endorse it and play it well, they could see good monetization out of it. Way better than a cam room would do.”

If “retire early, put your avatar to work” seems like a scenario ripe for the often dystopian, sometimes utopian British anthology series Black Mirror, it’s because an anxiety about the impending rise of VR and AI seems to be permeating our entire culture in 2018.

The VR evangelists and enthusiasts I’ve spoken to deflect that vertigo with a flip-side reaction: They embrace the future and can’t wait to plunge into it head first. The way Sutra and his team unguardedly talk about “securing assets,” “immortality,” and turning copies of people into “puppets” might sound a little sinister to the layperson. But like most people active in tech, they simply see themselves as visionaries, pioneers in a field that hasn’t been charted yet. They are convinced that the future will unroll the way it will, and that there is nothing dystopian about it.

I spoke with Anna Lee, whose company Holofilm Productions had attempted avatar-based technology for VR using motion capture years ago. “We did a digital rendering demo of [performer] Tera Patrick. We launched it and debuted it at AVN in 2014.” This year, she visited the Camasutra VR booth and was extremely impressed by the advances they made. “There are things that you can’t achieve in live action that you can achieve flawlessly through digital scanning and animation and, inevitably, with AI,” she says. “The scans are going to become so photorealistic that you won’t be able to tell the difference.”

“VR might be ‘confined’ to the headset now,” Lee told me, “but it won’t be for long.” She pointed to Blade Runner 2049, in which Ryan Gosling’s virtual girlfriend is able to follow him around the apartment through an elaborate array of cameras and projectors, or be uploaded onto a penlike device and taken out for dates. “Once we’re free from the headset, we have to find ways to customize the experience,” Lee says. “That future is coming. It’s not a matter of if but of when.”

The two extreme reactions to our fastly approaching VR future—vertigo and evangelism—are easier than trying to navigate a middle path, a critical engagement with the new technologies while acknowledging the unease that is produced by their compulsory introduction into everyone’s lives.

The ambivalence and sense of future-shock that performers like Honey Gold and Donny Sins felt when I brought up these issues, but didn’t experience automatically when they answered the siren song of the technologists, shows why this is an important conversation to keep having. We’re really still at the research-and-development phase of VR. Even referring to this space by the innocuous initials “VR” is just a handy way to bypass the thorny complications of what is already proving to be a completely new way to design experience.