It’s hard to imagine David Hockney, of all people, putting a foot out of line in the eyes of the art-world establishment. Every few years, he tops auction charts for works by living artists. His body of work cultivates a utopic nostalgia that transcends place, time, and age. At 85 years old, he’s still practicing his craft. But this week, he incited pearl-clutching among London’s art critics with his latest display of work: an “immersive” projection installation of his paintings, digital art, and set designs.

The past few years have birthed a crop of animated warehouse showings of works by long-dead artists. With their work’s entry into the public domain, Frida Kahlo, Vincent Van Gogh, Salvador Dalí, and their household-name ilk make for low-cost, high-return, Instagram-ready spectacles of large-scale projection art, music, and plentiful selfie opportunities. They have all attracted widespread critical disdain, but the most damning indictment of the “immersive experience” is its inclusion in every snob’s favorite hate-watch: Emily in Paris.

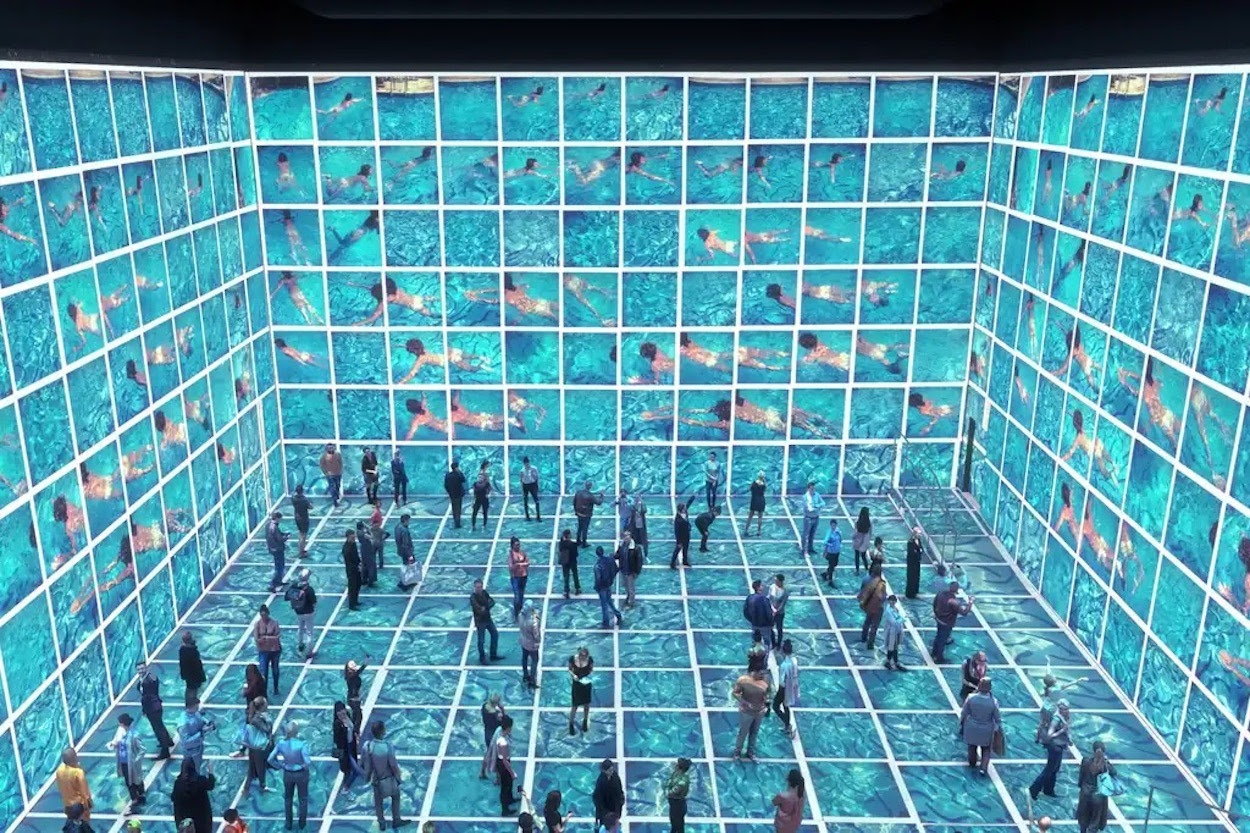

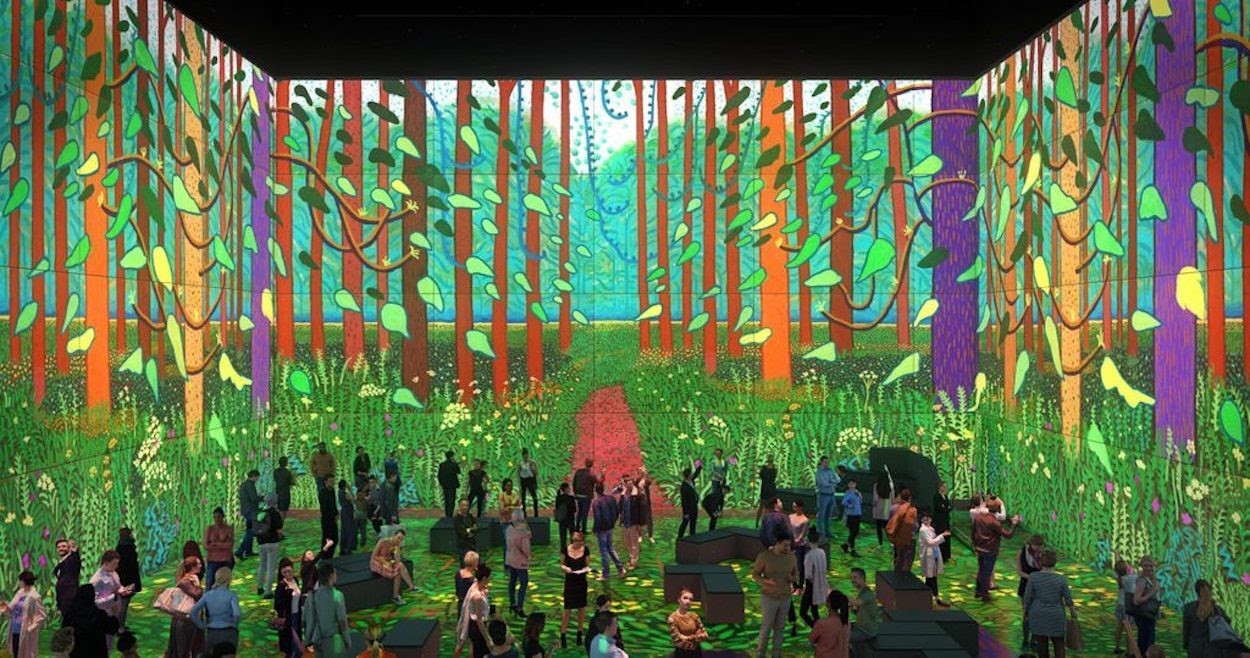

Hockney seems to think his take on the immersive experience is poised to buck the soulless-selfie-factory trend. After all, he is the only living artist to lend creative direction to his own survey fantasia, “Bigger & Closer (not smaller & further away),” on view at London’s Lightroom through June 4. In it, his works are projected to an orchestral score, with his own musings about his process and vision interspersed.

Teardowns from London press include “the kitsch is not just a twinkle but an overwhelming crescendo,” and two-star ratings from both the Evening Standard and the Guardian. Amid all the noise, though, Hockney seems unbothered. “My work was leading up to this, really,” he told the New York Times, where he also shared his hope for the show’s ability to draw in young artists and inspire them to see the potential of digital mediums.

The critical blowback for installations like “Bigger & Closer” is often pegged to the absence of a critical, curatorial eye, or the artwork itself being taken out of context. The subtext seems to be more an indictment of the ways young people are choosing to engage with art: instead of exuding pious reverence for art by looking up from their phones to take it in, they’re making technology part of their process. Perhaps it should come as little surprise that Hockney—himself an early adopter of technology in art—is more concerned with appealing to them.

“I don’t care what critics say about me. I think it’s really good,” the artist told the Times, “and if I think it is, that’s all that counts.”