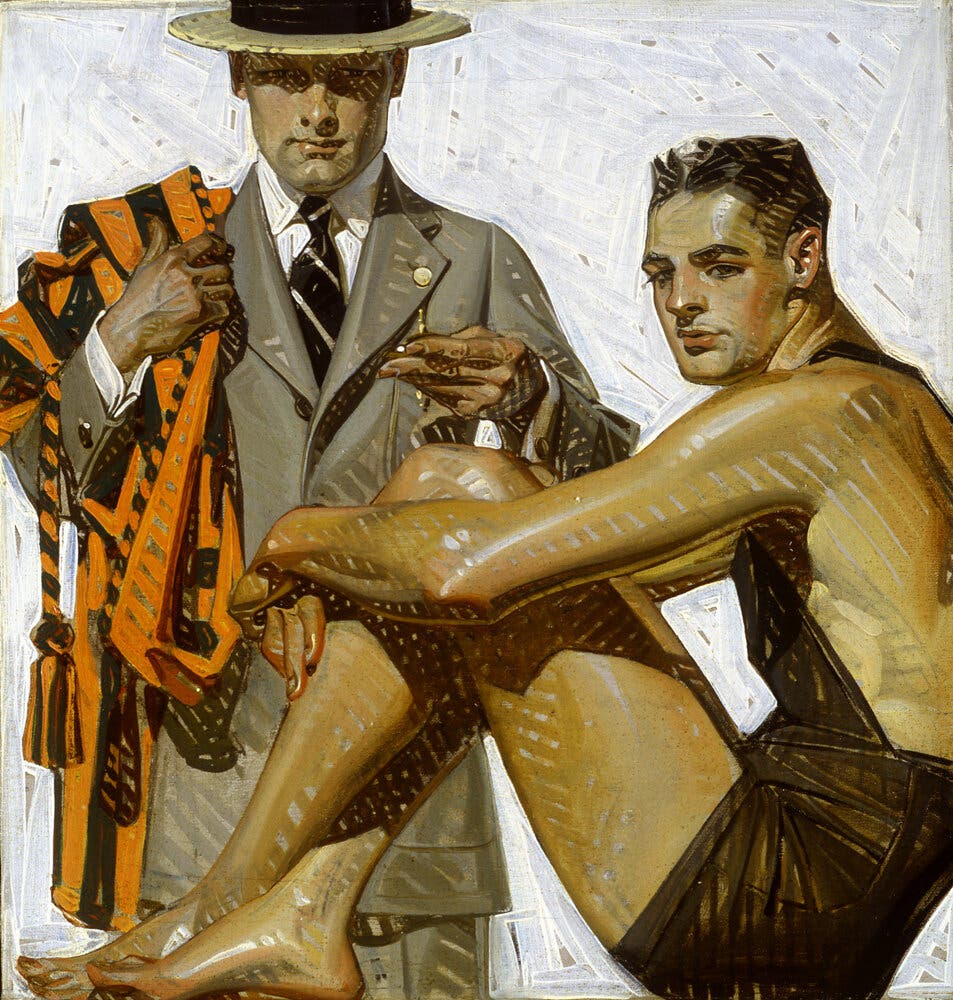

J.C. Leyendecker illustrated countless magazine covers and ads throughout the early 20th century, but one in particular brilliantly showcases the subversion the queer German-born painter often hid beneath the surface. The crisp canvas depicts a robe-clad male model examining a bar of Ivory soap before a bath. Look closer and one shadowy detail becomes hard to unsee: it suggests an erection. A covert sexual gesture may seem unlikely to clear Madison Avenue, but for Leyendecker, they were standard fare. He slyly brought ads suffused with homoeroticism to the masses during his zenith in the Roaring Twenties; they now star in a current show at the New York Historical Society.

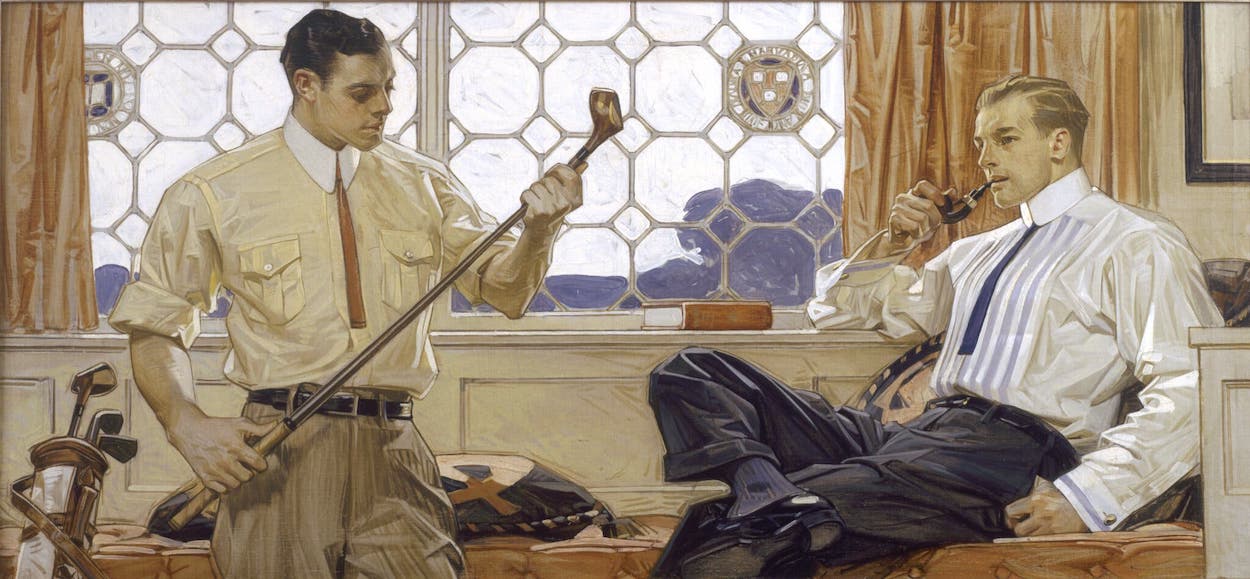

Leyendecker, who studied in Paris and trained in Chicago before settling in New York in 1902, is most remembered for depicting the “Arrow Collar Man.” An early 20th-century sex symbol who hawked crisp collars and cuffs, the suave hunk’s all-American allure proved potent, shaping the era’s Gatsby-esque aesthetics and spawning loads of fan mail. (Daisy Buchanan even name-drops him in The Great Gatsby.) In reality, the figure was modeled after Charles A. Beach, a model and Leyendecker’s life partner. They delighted in depicting men whose breezy, detached demeanors don’t tell the full story, leaving one’s mind to wander.

Millions of Americans were exposed to Leyendecker’s visuals—he was behind 322 covers for the Saturday Evening Post, one shy of protégé Norman Rockwell—perhaps an indication that homophobia wasn’t nearly as aggressive in the Jazz Age, and LGBT individuals had space to thrive. Still, his commercially successful style fell flat in the ‘30s, when the unsparing realities of the Great Depression shifted the national mood away from Art Deco stylings and flapper dresses to cautious conservatism. But it’s difficult to imagine Abercrombie & Fitch catalogs or Calvin Klein underwear ads existing without his influence.