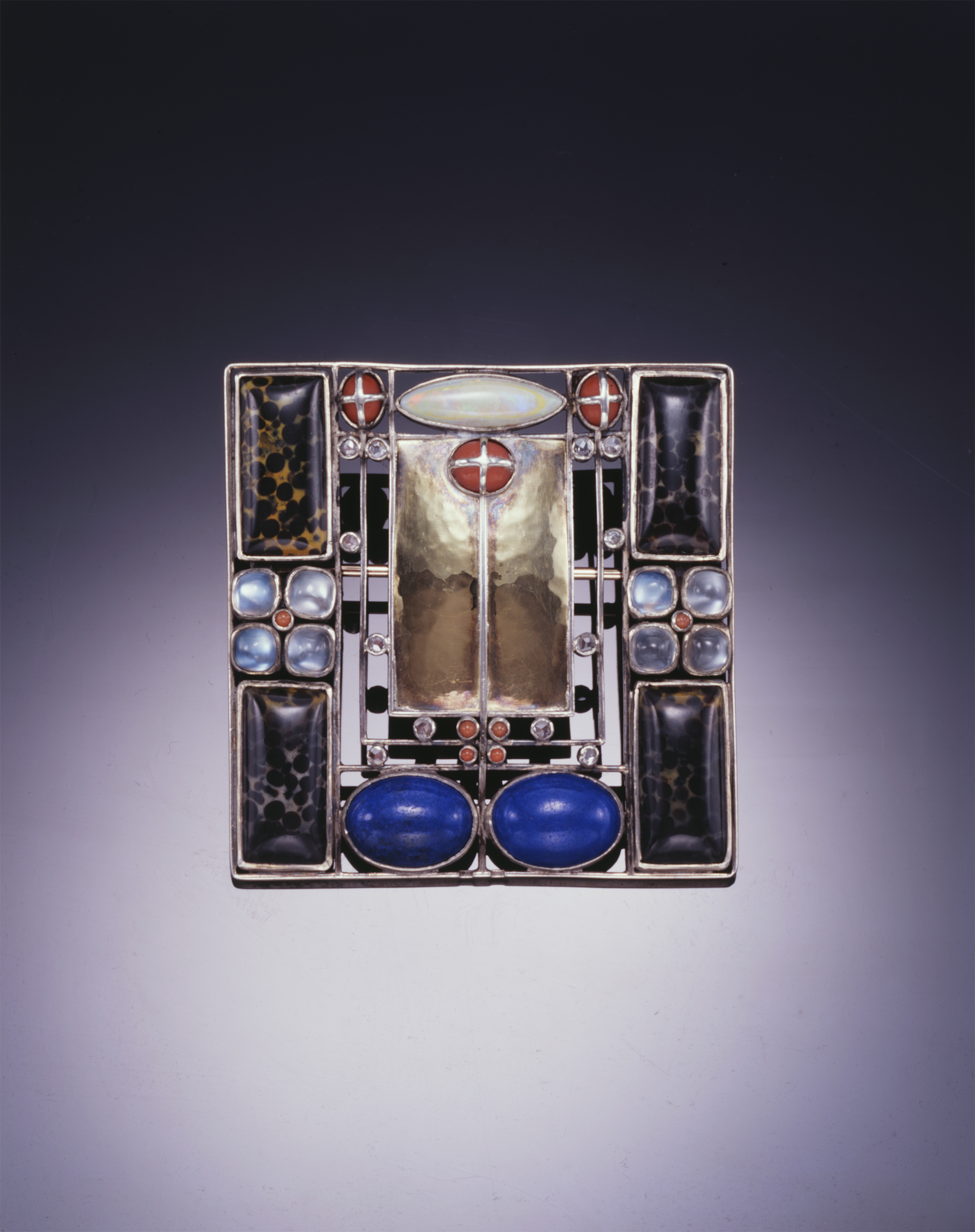

Even if you’ve never heard of Wiener Werkstätte, the Vienna-based collective of master artists and craftspeople, you probably know of its originators, Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser. Beginning Oct. 26, New York’s Neue Galerie explores the collective’s lesser-known luminaries, as well as the evolution of its aesthetic, benefactors, and mediums, in “Wiener Werkstätte 1903–1932: The Luxury of Beauty.”

“The most remarkable thing is its scale and scope,” says co-curator Janis Staggs. “If you could think it, they could make it.” This was mostly thanks to the Werkstätte’s first financial backer, Fritz Wärndorfer, who endeavored to outfit his home as a Gesamtkunstwerk—a total work of art. In turn, the collective expanded its focus on work in metal to include furniture, wallpaper, textiles, fashion, bookbinding, ceramics, and glass. Each piece served as a status symbol for the cultural elite and helped shape the look and feel of domestic design. “You can see the Werkstätte’s artistic variety augmenting [the scene] almost like a foghorn over time: it started off muted, but by the end, you can’t necessarily speak of a style because it’s so all over the place. They were trying to appeal to everyone at the same time,” Staggs says, noting that the workshop, often on the verge of bankruptcy, diversified into less expensive, more approachable objects in hopes of reaching a broader market.