On May 23, one of the last remaining public payphones was removed from New York City’s streets. The dismantling signaled the end of an era for most New Yorkers, who grew up accustomed to city life where, at one point, you couldn’t walk 30 feet without finding one. Before the smartphone era, New Yorkers relied on payphones to make quick calls on the go—even if it meant fumbling for a quarter in your bag and feeling cramped inside a smelly booth for a few minutes. What was once an inimitable fixture of city life quickly became obsolete in 2015 when CityBridge began installing LinkNYC kiosks that offer public Wi-Fi and smartphone charging stations.

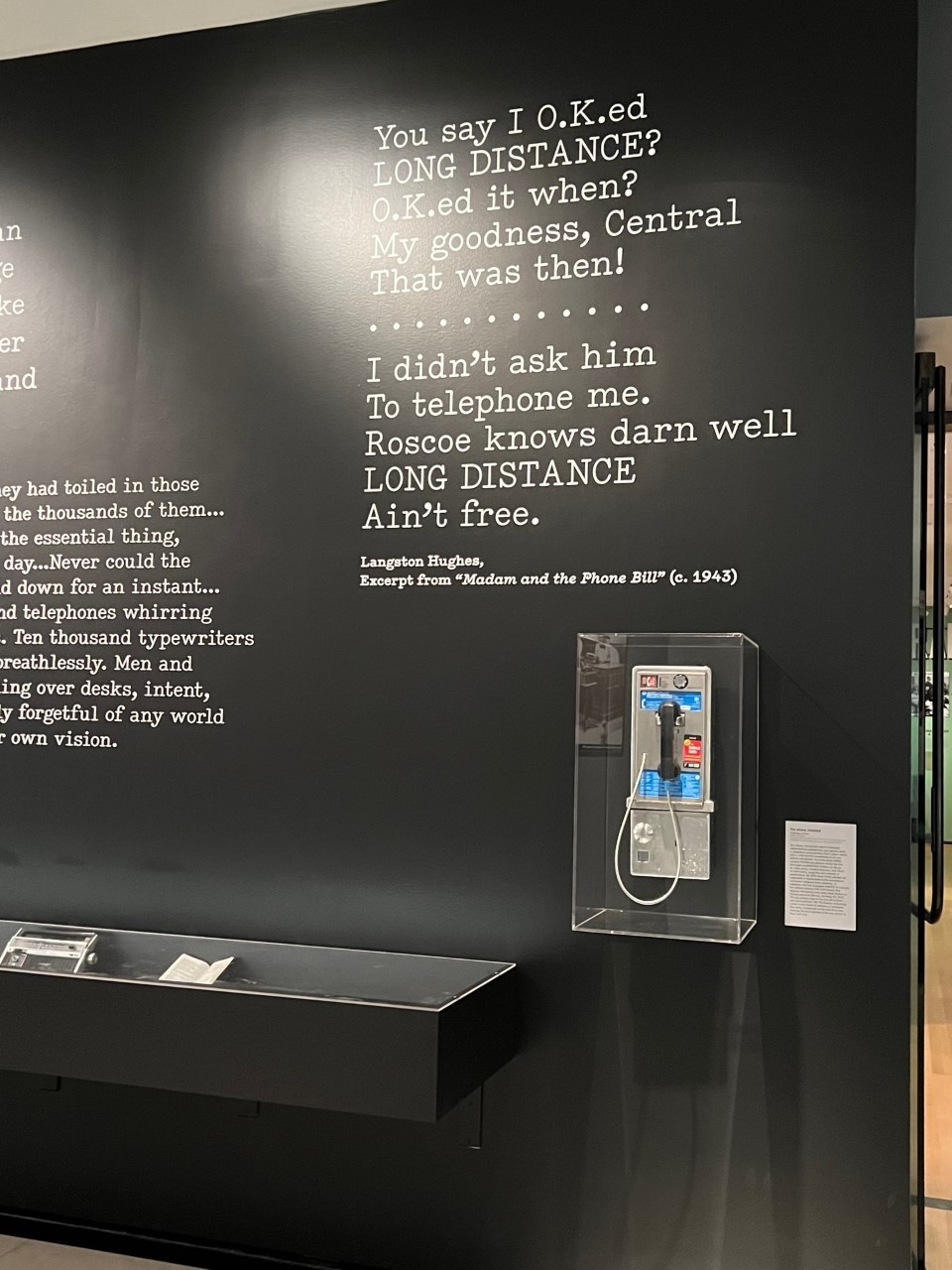

Though public payphones remain little more than a distant memory, they aren’t gone forever. The booth was quickly snapped up by the Museum of the City of New York, which serendipitously had just opened “Analog City: New York B.C. (Before Computers).” The exhibition takes visitors back in time to pre-digital New York to show how once-pioneering objects like rotary phones, rolodexes, and typewriters laid the groundwork for the city to thrive as a hotbed of finance, news, research, and real estate. It sits directly underneath a related Langston Hughes verse: “I didn’t ask him / to telephone me. / Roscoe knows darn well / LONG DISTANCE / ain’t free.” Today, of course, Roscoe could’ve just slid into his DMs.

Beyond simply reminiscing on obsolete objects, the show prompts reflection about how these analog relics succumbed to today’s most prevalent technologies. “Just like we transitioned from the horse and buggy to the automobile, and from the automobile to the airplane, the digital evolution has progressed from pay phones to high-speed Wi-Fi kiosks to meet the demands of rapidly changing daily communications needs,” Matthew Fraser, the city’s chief technology officer, tells the New York Times.

For example, one would be hard-pressed to find a single filing cabinet in the tricked-out office of a tech startup, but the hulking bins revolutionized how paper is stored and accessed and continue to inform basic terminology vis-a-vis computer storage, such as saving files in folders. As the hunger for real-time information intensified as institutions like the New York Stock Exchange grappled with ever-increasing volumes, the prevalence of digital file storage quickly took hold. Factor in sustainability concerns and the tendency toward paperless operation, and demand for the filing cabinet has been in steady decline.

Ditto for typewriters and their Linotype forebears, which were adopted by the New York Times in the 1870s to set type for its newspaper pages. “Prior to this, all printed materials had to be laid out by hand using individual letters,” Lilly Tuttle, the show’s curator, tells Artnet News. “With the Linotype, the paper could print more pages and more frequent editions. It allowed for an incredible boom in the amount of printed materials that were available around the world, and for expansion of the news media as well as literacy.” Though the machine all but transformed the act of typesetting, they’re virtually absent in today’s media landscape, where news outlets churn out an endless deluge of clickbait and anyone can send Substacks to thousands of readers.