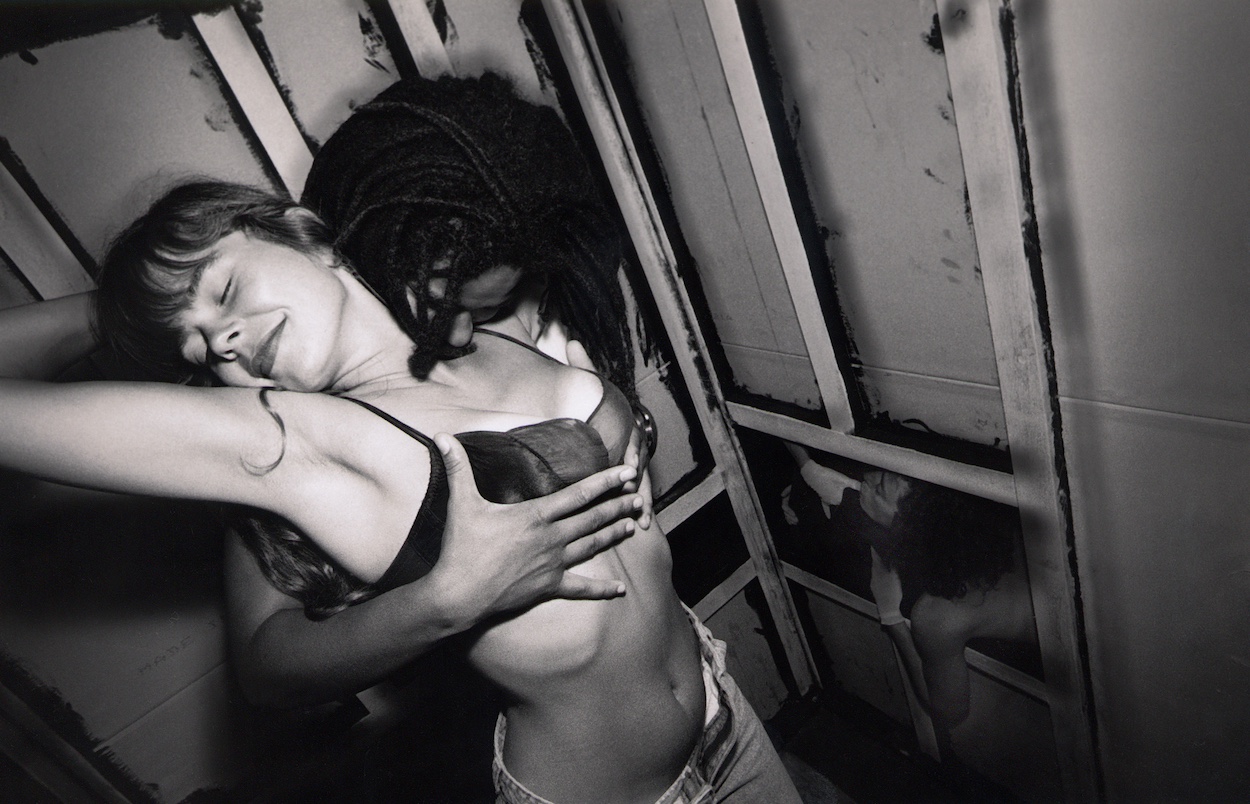

The history of the built environment is, in many ways, the history of sex, of humans creating spaces to explore their natures. Queer people are inseparable from these histories, but in the last quarter of the 20th century in America, they became vibrant actors in determining the possibilities of public sexuality.

They demanded presence, the end of those strictures that kept them hidden because of whom and how they loved and lusted. They asserted the right to be in public—and they appropriated public space to create more private queer spaces in which they could build cultures outside of the straight gaze.

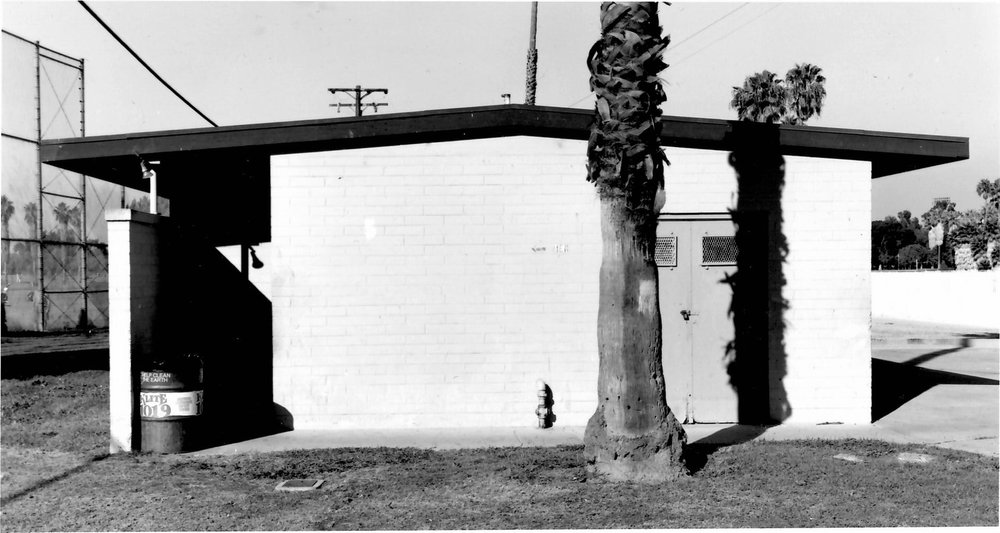

“Radical Perverts: Ecstasy and Activism in Queer Public Space, 1975-2000” shows what can arise when queer people have architectural and cultural agency. It takes its name from a declaration by San Francisco lesbian S/M organization Samois, and its checklist from many of those most adventurous queer artists of their times: Nayland Blake defines space early in the show with their Workroom 2, a screen that also might function as a series of glory holes for an enviable broad assortment of bodies.

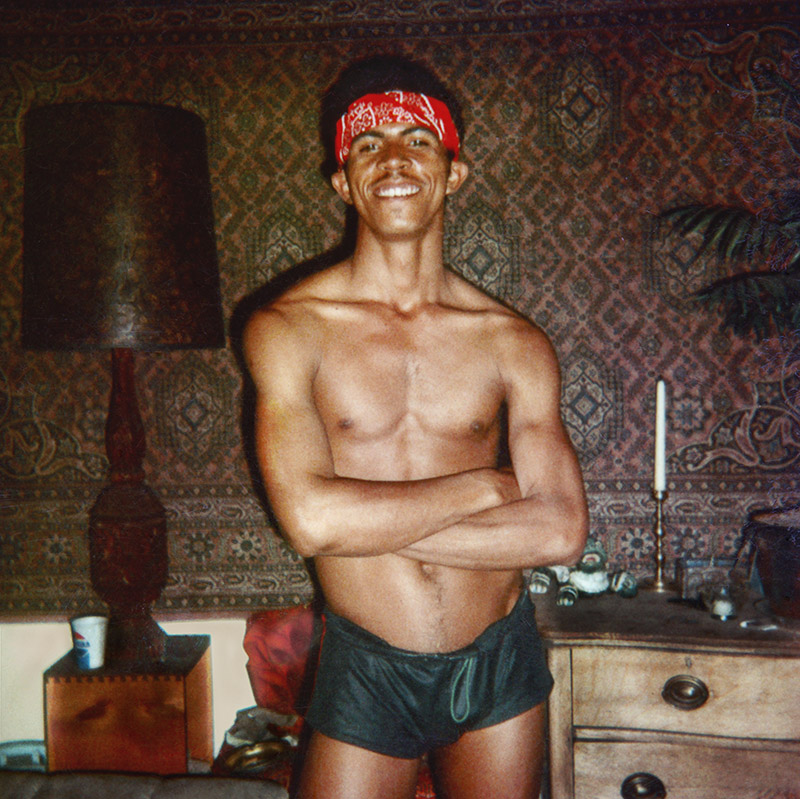

Deeper in, photographer Frank Morello’s The Fairoaks Project documents the men who populated a hotel turned gay commune-cum-bathouse in late-’70s San Francisco—and the rooms they found each other in—for a series of Polaroids that vibrate with the erotic charge of interior design.