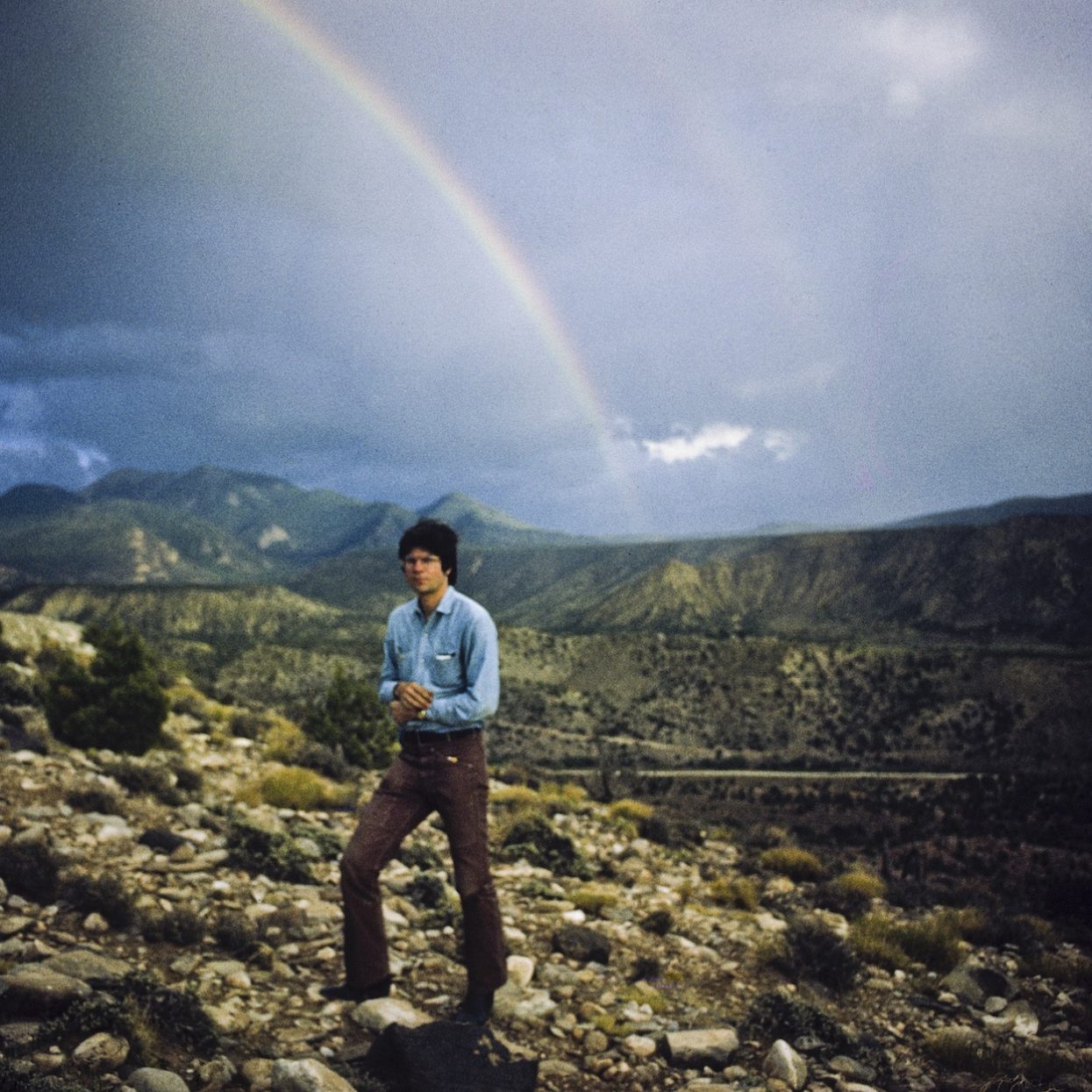

Robert Smithson was a scrappy 22-year-old unknown when a painting imbued with Catholic mysticism caught the eye of a Roman gallerist in New York, kickstarting his career and a benefactor relationship with arts patron Virgina Dwan. He’d go on to briefly flirt with Pop and Catholic art, but pivoted to earthen materials. He started exploring industrial areas in his home state of New Jersey and became transfixed by trucks excavating tons of earth and rock. That yielded a trove of sculptures made from industrial materials in the ensuing years—and a lifelong fascination with the thermodynamic principle of entropy. It would be some time, though, before he realized the monumental Land Art opuses that expanded what art could be and where it could be found, and have come to define his legacy.

Chief among these is Spiral Jetty (1970), a giant earthwork made of mud, salt crystals, and basalt rocks forming a 1,500-foot-long hypnotic coil jutting out from a remote part of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. He’d realize one more—Broken Circle/Spiral Hill in the Netherlands—but died in 1973, at age 35, in a plane crash while photographing the almost-complete Amarillo Ramp in Texas. (His wife, fellow artist Nancy Holt, completed it one month later.) While Smithson’s outsize impact on Land Art is well-documented, his works face a precarious future amid a warming climate. Heavy rains submerged Spiral Jetty by the time he died, and it would only reappear a few times until 2002, when droughts shrunk the lake by two-thirds.

His extant works are in good hands with Dia Art Foundation and the Holt/Smithson Foundation, which Holt willed into being upon her death, in 2014. But perceptions of Land Art are shifting. One of Smithson’s works saw him dump a giant barrel of industrial glue in British Columbia; others question the ethics of white artists making permanent works on Indigenous lands. The notion that Land Art is rife with masculine gestures—egotistical monuments disturbing nature to valorize the sole creative genius behind them—is also inescapable. (See Michael Heizer’s behemoth, City.) But, five decades after Smithson’s death, his beguiling art continues to lay the groundwork for those eager to explore our relationship with the planet.