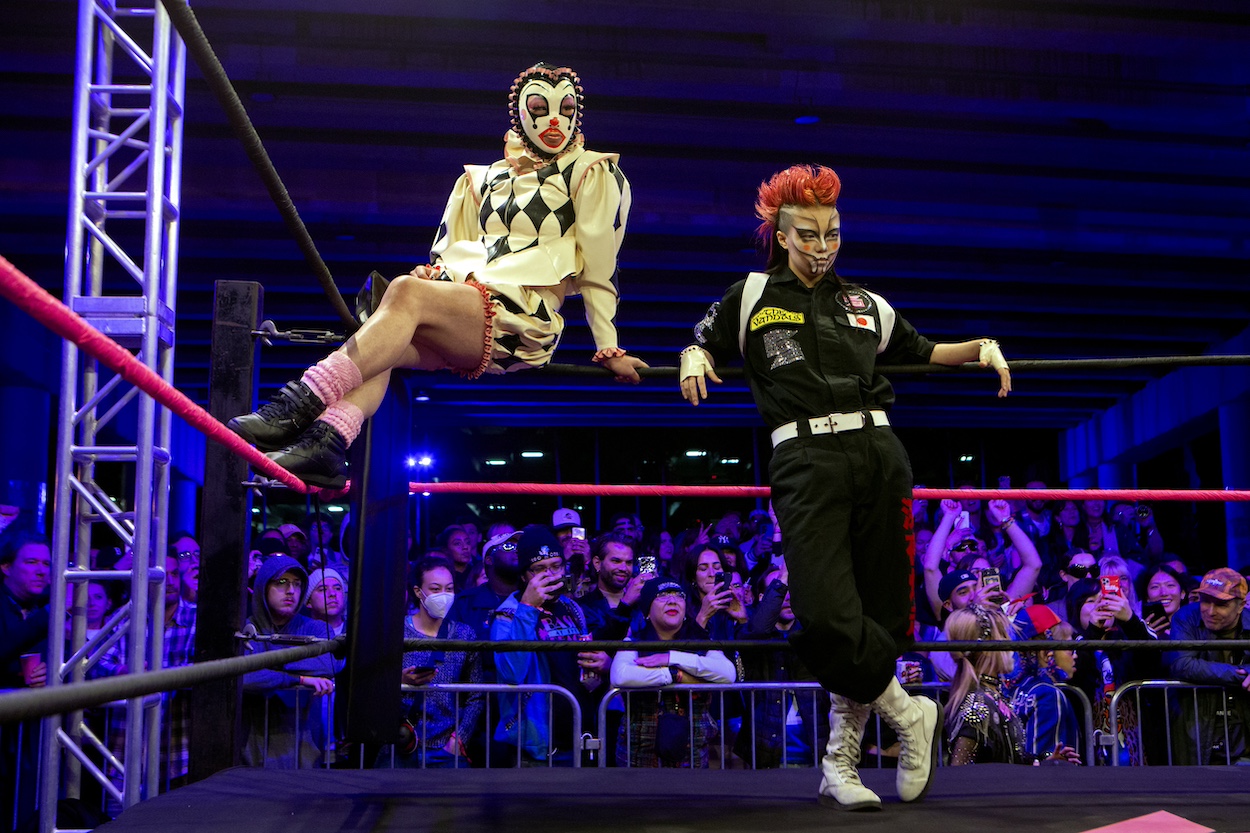

Overhyped art shows mounted on megayachts, star-studded ragers with perilously long lines, and Uber’s laughably high surge pricing are all par for the course during the overly corporate and slightly surreal Miami Art Week, but one event on last week’s crowded calendar seemed to promise something different. More than 2,000 eager spectators crowded into Downtown Miami’s buzzy Lot 11 Skatepark on Wednesday night to watch the championship match of Sukeban, the Japanese women’s professional wrestling league. Skeptics of the WWE’s melodramatic machismo were in for nothing of the sort that night, which played out more like a “riot girrrl–themed drag show.” Power moves were on the menu, but so was a spirit of rebellion and showmanship aiming to destroy the barriers between art and wrestling with a dynamic alchemy of fashion, anime, music, and storytelling.

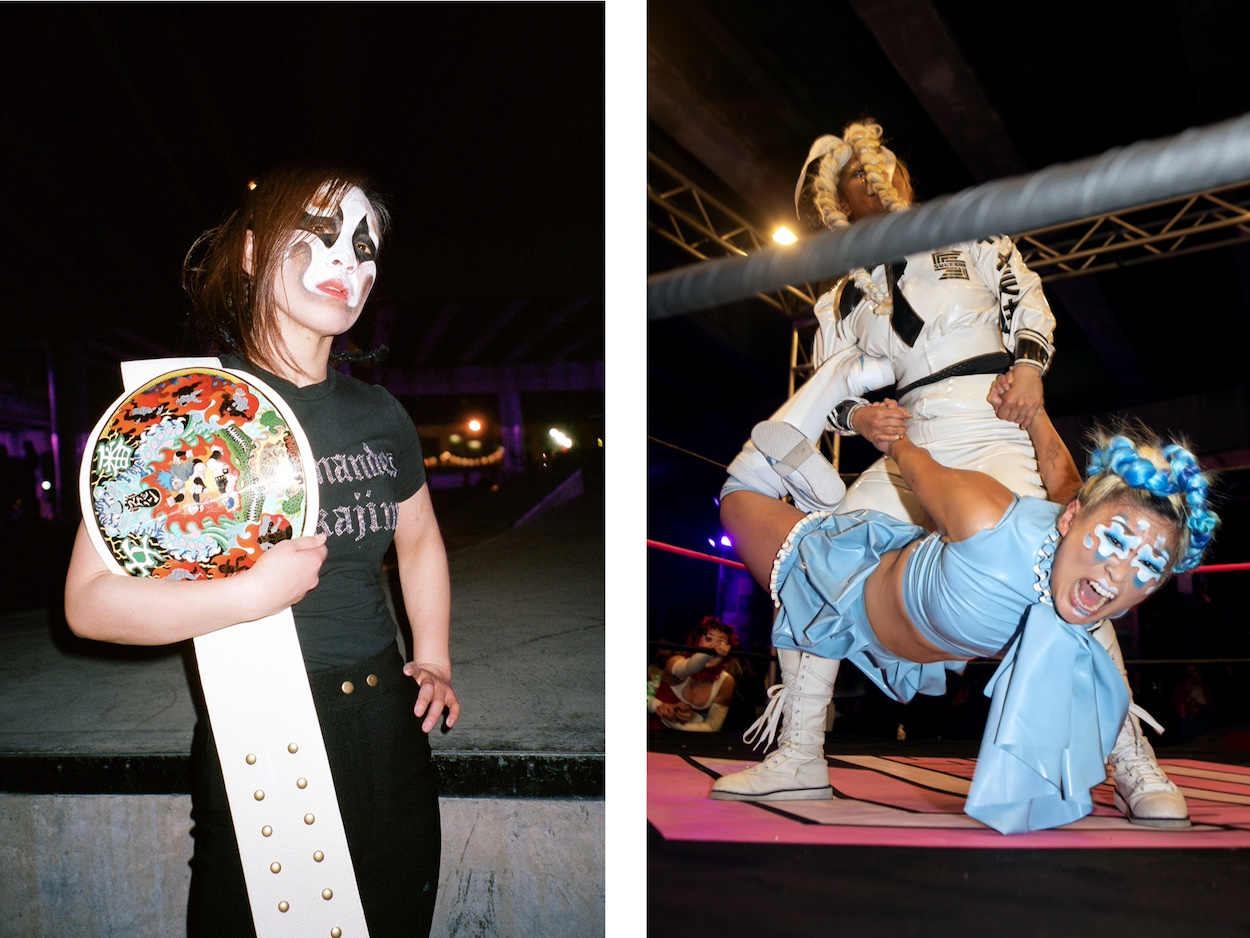

Sukeban wrestlers, much like drag performers, cultivate over-the-top personas and backstories that coalesce into a performance-art spectacle of choreography, comedy, and pageantry. On the roster were names like Bingo, “the resident evil clown,” as well as Commander Nakajima and Countess Saori, two villainesses dressed as Victorian-era goths.

Helping bring each wrestler’s character to life are lavish, flamboyant costumes—the group effort of fashion designer Olympia Le-Tan, milliner Stephen Jones, makeup artist Isamaya Ffrench, and nail artist Mei Kawajiri. Each costume is meant to summon the performer’s strengths and idiosyncrasies—and give a brief history lesson. The name “Sukeban” originated in a subculture that became prominent in the 1960s, when packs of “delinquent girls” rebelled against the Sexual Revolution that was taking hold in Japan. Their drug use and modified schoolgirl outfits, which sported long skirts designed to conceal weapons, rebuffed the country’s rigid gender norms.

That ethos of defiance was on full view last week. “It is very important to carry on the legacy of sukeban, not just in pro-wrestling, but in creating a new world,” wrestler Ichigo Sayaka told Vogue. “We can’t just fulfill the wishes of higher-ups; we need to find our own meaning in life, by getting involved and fighting for the things we believe in.”

After a marathon of six matches, Commander Nakajima defeated Sayaka with a schoolboy rollup to become the first Sukeban World Champion. Bull Nakano, the Japanese wrestling legend, handed off the championship belt, a Marc Newson–designed leather showpiece whose central plate uses the cloisonné technique to reflect illustrator Ayako Ishiguro’s vivid portrayal of seminal moments in wrestling history. Emblazoned with Siamese crocodiles and surrounded by the claws of a blue dragon, the artwork sparks comparisons to Hieronymus Bosch’s depiction of hell—an apt nod to the equally mesmerizing and menacing energy each performer brought in the name of empowerment and rebelling against society’s expectations.