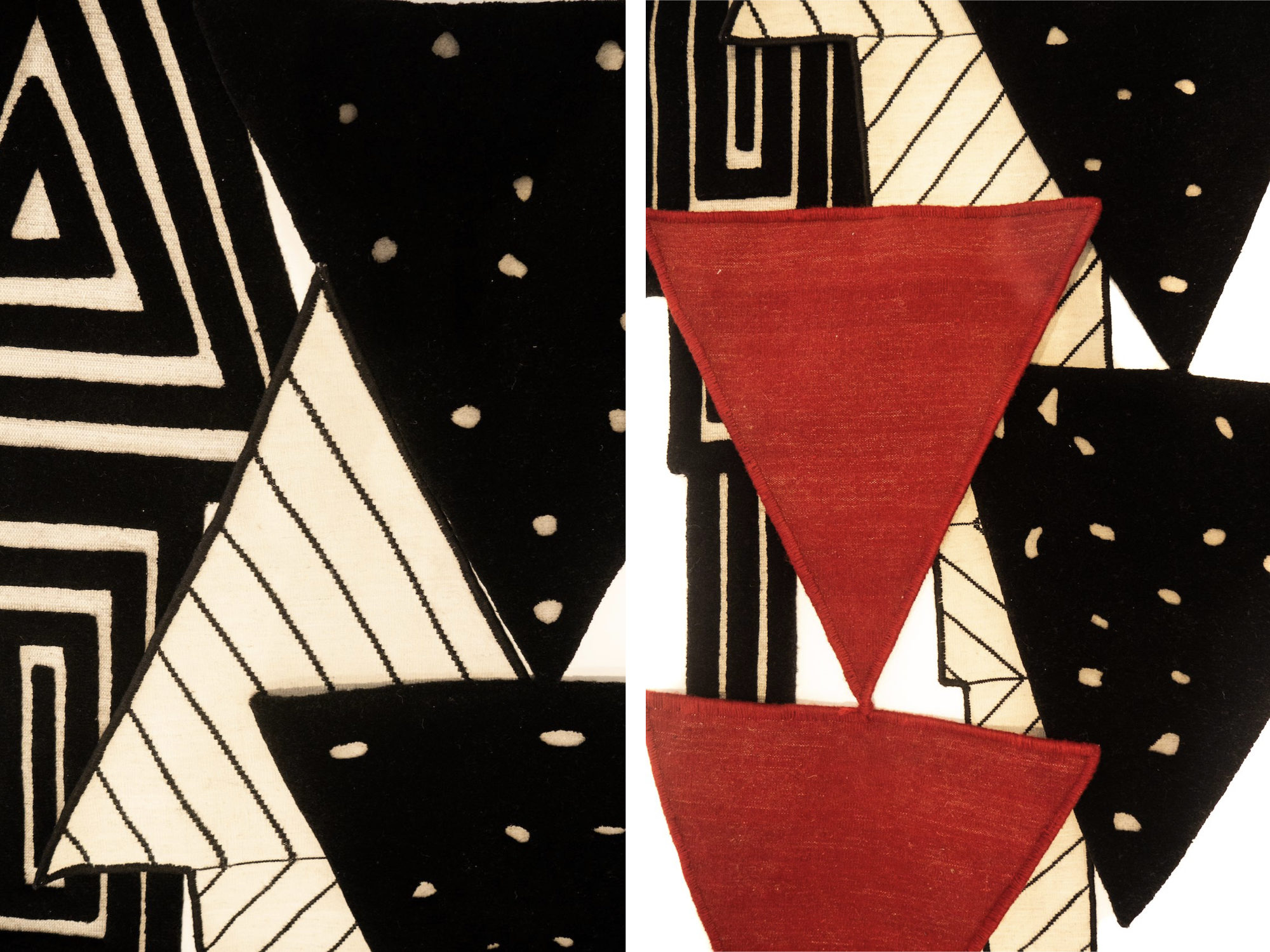

At the rather green age of 35, Taher Asad-Bakhtiari has already lived several lives: The self-taught Iranian artist cycled through various ventures in experience and event design (he also ran a creative agency) before finding his way to weaving at the suggestion of his mother, a retired patternmaker. Since then, he’s triangulated between the U.S., Tehran, and more recently Dubai, his home for the last five years before relocating to New York. The lively Middle Eastern hub served as “an amazing platform to start something new with my life and get the word out,” Asad-Bakhtiari says. So it is with a renewed focus on ancestral craft that he prepares for the launch of an exclusive collection of his reimagined kilims and gabbehs—produced in collaboration with a tribe of semi-nomadic Iranian and Afghani women as part of his ongoing Tribal Weave Project—at New York’s Met Breuer in September.

The opening is the latest feather in the cap of the rising star, who received an industry boost this year during New York’s International Contemporary Furniture Fair, where he launched an expansive collection of textiles with Bernhardt Design—the brand’s first collaboration with an artist of Middle Eastern descent, and Asad-Bakhtiari’s first venture into commercial design.

While the commissions and accolades seem to grow with each new project, Asad-Bakhtiari says landing on woven textiles as a medium was, until recently, a bit “like a puzzle.” Growing up in a creative family, however, clearly shaped his artistic leanings. His great aunt is Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, among the most prominent contemporary Iranian artists of the last century—and the first woman in Iran to have a monographic museum inaugurated in her honor. His mother, who studied fashion design at London’s Central Saint Martins, introduced him to the weavers with whom he currently works. Witnessing their engagement in primitive, increasingly rarified techniques proved to be a serendipitous boon for the young artist.

“My family comes from an Iranian tribe: This is their craft—this is their lifestyle. It all fit so well together. When it clicked for me, I thought, ‘Well, this world was meant to be mine,’” Asad-Bakhtiari says, with the verve that comes from an intimately personal passion.