The 1990s were a strange time for Japan. The country’s bubble economy burst in 1991, ending decades of rapid-fire growth following World War II. Four years later, the devastating Great Hanshin earthquake and sarin gas attacks on Tokyo’s subways stoked widespread fear. At the same time, technology was progressing—the advent of Windows 95 popularized computers, cell phones, and gaming consoles while computer-controlled robots replaced assembly line workers. Enter the “Lost Decade,” a period when young adults struggled to find full-time jobs or simply didn’t work. Japanese people may recall the slogan of the times as ibasho ga nai, or “without a place to call home.”

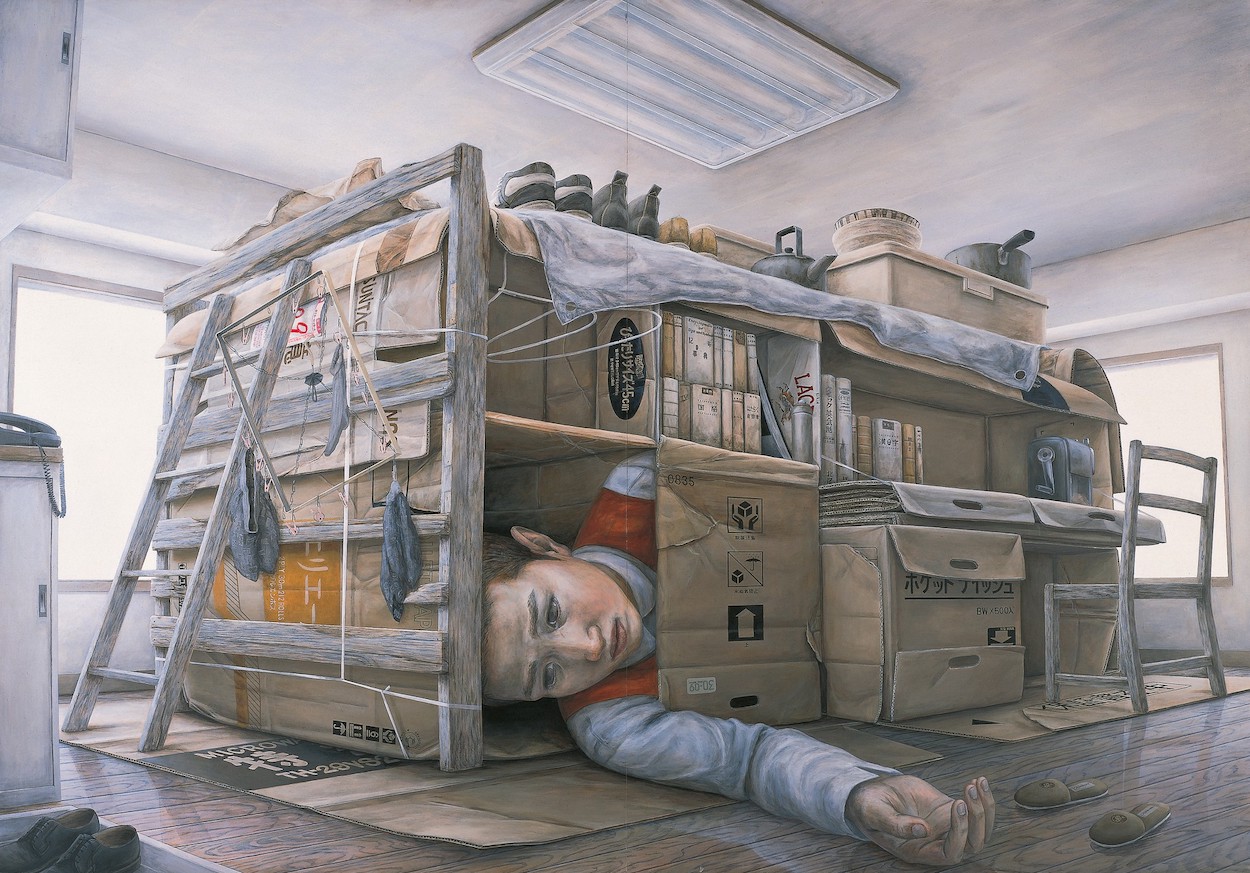

Tetsuya Ishida was coming of age during this precarious decade and, amid the economic stagnation, decided to translate his generation’s existential distress into paintings. Feelings of human alienation and hopelessness are palpable throughout his meticulously detailed canvases often depicting stoic-faced young men melding with everyday appliances, industrial machinery, and civic architecture. In one, suited salarymen laying supine on a conveyor belt are dissected, almost robotically, by scalpel-bearing factory workers, nodding to the punishingly long hours expected from both collars at the time. Other lost souls simply became hikikomori, or recluses who withdrew from society and often refused to leave their bedrooms, a visual Ishida captures viscerally in the joyless Untitled (1998).