In 1977, Michael Brody opened a thumping queer club in a Lower Manhattan parking garage. The following year, after installing a sprung dance floor and a peerless Richard Long sound system, it became Paradise Garage. When it closed a decade later, it had changed the world.

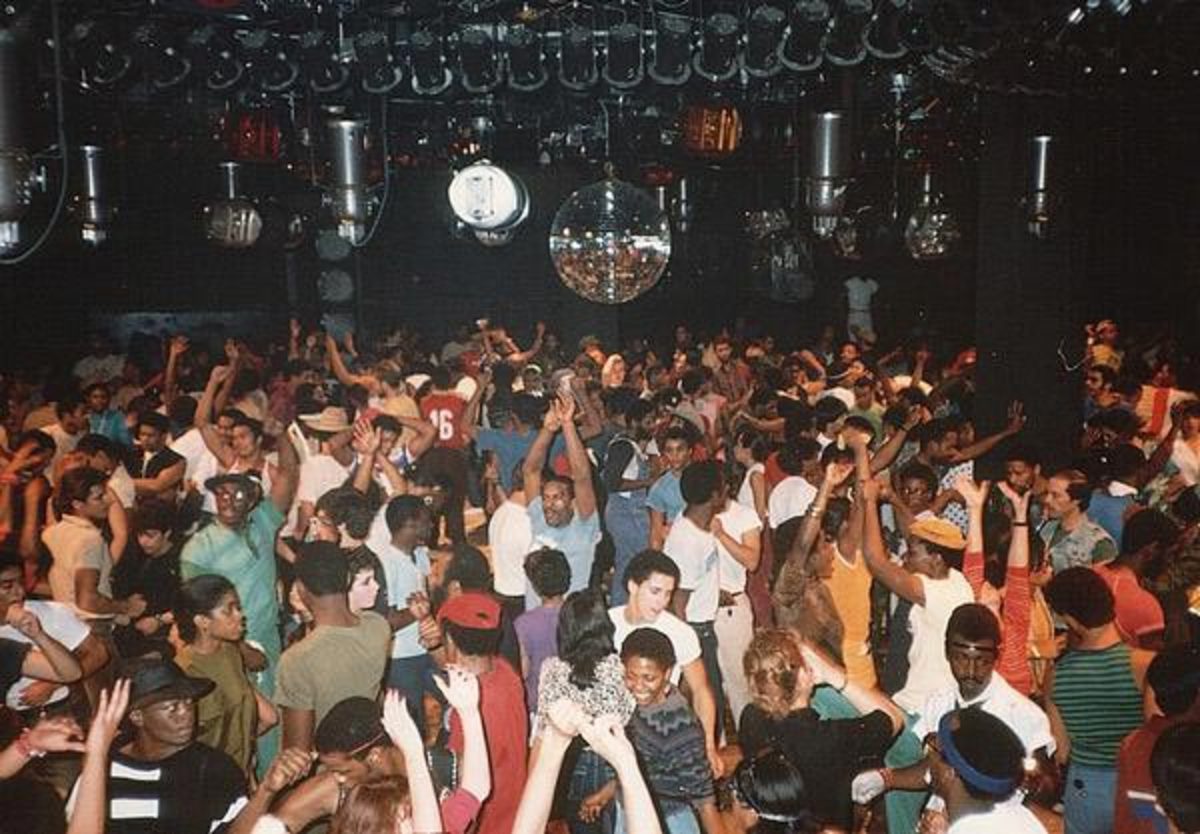

With resident DJ Larry Levan and a vibrant crowd of mostly Black and brown queer revelers, the club created an unparalleled and welcoming vibe, while cementing ideas around the music selector as music creator and the sound system as space makers. As a hub of organizing—it was among the very first fundraisers for Gay Men’s Health Crisis, the AIDS advocacy organization that now owns the club’s trademark—the club proved nightlife can be a political force. Its legacy lives on every time a dancer hits the floor and finds their people, lost in music, in that bliss of being in and out of their bodies at the same time.

Lincoln Center isn’t the first place one might think of when contemplating the queer Black bliss the Paradise Garage made a home for and out of. The complex of High Modernist buildings housing temples to High Culture is far from the Paradise Garage’s after-dark sweat-fests, and even further from the club’s progeny out in Bushwick and beyond. “Architecture can be welcoming or forbidding,” says Jon Nakagawa, Lincoln Center’s senior director of contemporary programs. “Architecture may be a barrier to people coming, so we’re trying to gradually create safe spaces,” he says, in which “people feel like they belong.”

To that end, for this year’s American Songbook series, Lincoln Center invited George C. Wolff to remember, or perhaps resurrect, spaces that embodied that belonging. On April 14, Lincoln Center turned over its David Rubenstein Atrium, a slightly awkward wedge designed by Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects just off the main plaza, to Eric Sosa and Michael Zuco, the team behind C’mon Everybody and Good Judy, two of Brooklyn’s crucial queer nightlife spaces. Pushing the atrium’s surprisingly good sound system, its small capacity, and its strict 10 PM curfew to their limits, “A Tribute to Paradise Garage” nimbly sidestepped nostalgia, gathering a packed house of partygoers for a trio of performances that paid tribute to Levan and his world without paying fealty to it. “We didn’t want to replicate the Paradise Garage,” Sosa says. “We wanted to imagine what it would be like today.”

Opening DJ Samuella joyfully invoked the spirit, connecting the dots between, for example, Patrice Rushen and Beyoncé. Drag hip-hop deities The Dragon Sisters followed, with their full band and a full stack of tracks shouting out sex workers and altered states of consciousness as survival strategies. Sosa said they selected disco dolls The Illustrious Blacks to close because they fully embody the Paradise Garage promise, in which expert DJing is just as vital as flamboyant dancing: both have the ability to make a space your own.

Crowds lined up in hope of making it into the atrium, and when capacity denied them, they pushed their faces against the big windows and danced on the sidewalk. Inside, revelers danced to an updated American Songbook, one that includes Sylvester’s “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” and “Is It All Over My Face” by Loose Joints. Paradise Garage turned these songs into building blocks, city blocks, cemetery blocks, and the Illustrious Blacks asked the crowd to play with them again and build someplace new.

As Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” lifted us all, I shook my ass and laughed my face off with a Garage old-timer, our bodies building something between us. “Girl,” she said, “you belong on the dancefloor.” For a moment, we all did.