Here at The List, we’re curious about the culture of design, so who better to survey about the field’s current state than those currently working at the top of it? In Need To Know, a weekly column, we pick the brains of best-in-class creatives to find out how they got to where they are today—and share an insider perspective on the challenges and highlights of their particular perch in the design world.

Winka Dubbeldam never had any doubt about the professional path she was destined to embark on, citing the desire and certainty that she would become an architect from a young age. Now, with projects in cities worldwide, Dubbeldam’s influence on the hyper-competitive field of architecture is undeniable. But the humble architect insists she wouldn’t be able to accomplish all that she does—designing, teaching at University of Pennsylvania, and traveling worldwide to secure and promote projects—without her team, including Justin Korhammer, her partner in design at Archi-Tectonics, the firm she founded in 1994. Surface caught up with Dubbeldam to talk about her origins in the field, thoughtful design, and the uniqueness of Archi-Tectonics.

Tell me how you got your start in the industry.

I guess I started by studying in Holland in the Netherlands, where I’m from. I graduated there, moved to the U.S., and did my post-graduate, my second masters at Columbia University.

Then I worked for the architect Peter Eisenman, in New York, and in 1994 I started my own office in a loft in SoHo. I decided early on I would be in academics, in order to be able to work on things I really liked. I think it’s a really important choice for an architect, how you want to grow your business, and for us, it was always staying really close to academics and being able to work on projects we are interested in with clients that are interested in architecture.

I chose to grow slowly but in the direction I wanted to grow in. And then we did a series of projects, and I guess I was quite lucky that early on, in around 1998, I started looking at possible developments with a private client who is actually from London. But he was interested in maybe developing a building, and that’s how we started our first large building, which was 497 Greenwich Street in New York. And that’s kind of the beginning, I’d say.

I’m wondering if your upbringing influenced the way you design, experience design, or think about design?

For one thing, Holland is a small country, so [the people are] highly educated and very cultural. I think that’s definitely helpful. The other thing is that because of my parents we had to move every two years. So we tended to go through a lot of looking for a lot, of building houses, redesigning houses. Very early on, like as a kid, I kind of knew that I wanted to be an architect.

What advice do you have for young professionals in the field?

My advice would be try to talk a lot about what you’re interested in. Participate in conversations, exhibitions, publications about architecture and see your work as part of a larger discussion.

I know that you yourself educate the next generation of designers at University of Pennsylvania, and I’m wondering how teaching students, in turn, has taught you something, either about yourself or the future of design or architecture.

Of course. I mean, you know, the reason why you are in academics is because you are interested in helping people move ahead, but also because it is really great to be in a discussion with your peers and with students. And that you eventually learn as much from your students as they learn from you, and the fact that you constantly have to prepare classes definitely helps you evolve on a continuous level.

I read a comment of yours about the Vestry project in which you talked about rejecting the concept of a formulaic floor plan that had identical units. That really resonated with me, because I hate the cookie-cutter feel of buildings that have identical units, and I much prefer a space with character. I’m wondering if you apply that framework to most of your projects?

Well the lecture I gave yesterday was very much about that—that I think that character and identity are not talked about enough in buildings. And I think that it’s very important to think what kind, more than aesthetics or or like those straight up accepted styles. You know I do believe in beauty, but I don’t believe in following styles. But I think beauty and character go together very beautifully, and sometimes in very unexpected ways. I think that is undervalued in society, that something that has character, you know for businesses it is very important, right? We did that Inscape project, the meditation concept. So that was on the forefront of our minds, like, how do you make a space that itself has to do, the concept has to do with meditation, so the space radiates meditation? And I really like how [Inscape founder Khajak Keledjian] said that the architecture became his 3-D branding; I think that’s a big compliment—that’s what we work on really hard.

I’m wondering if you have any new projects that you want to chat about and spotlight?

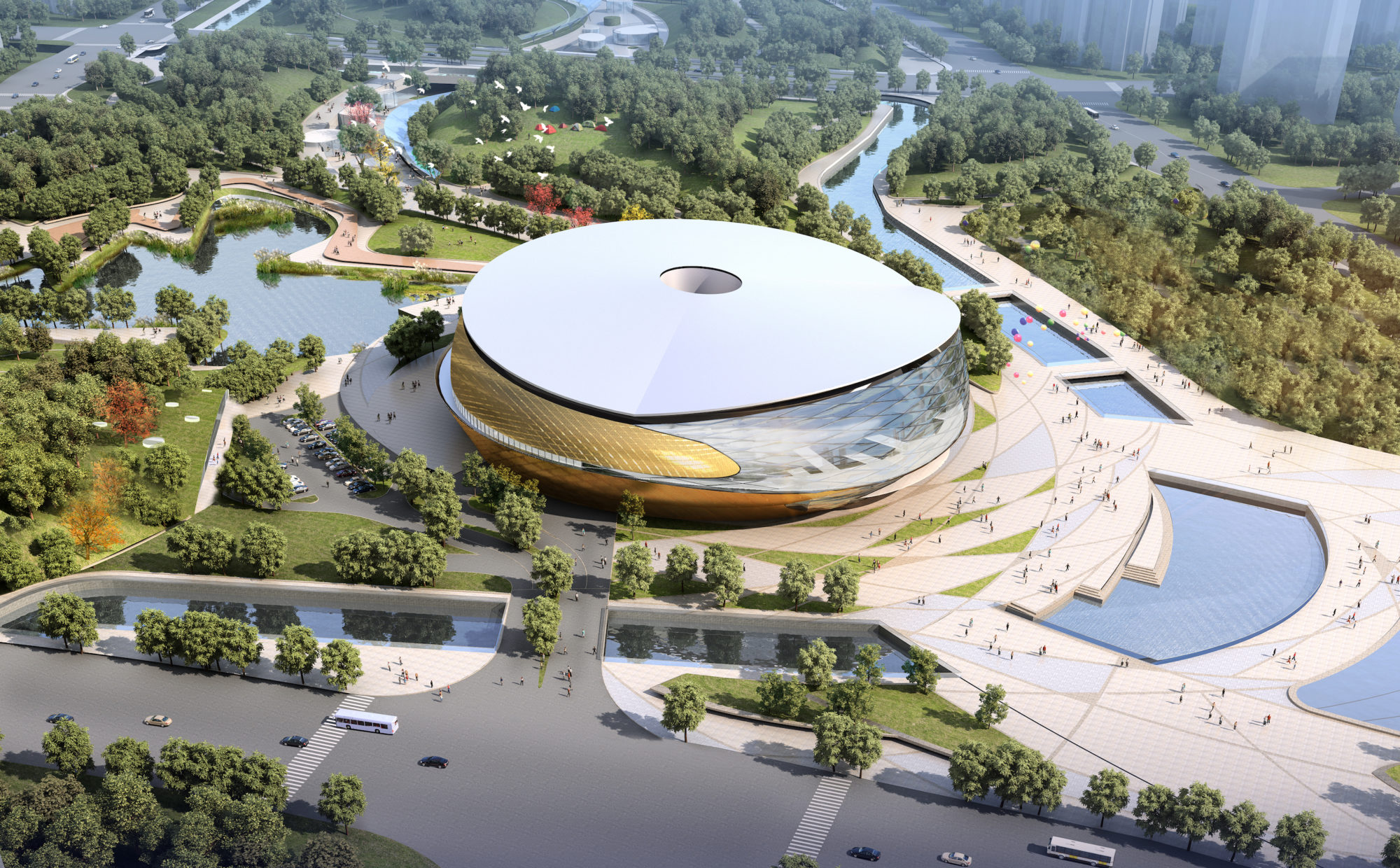

Yes! We just just won a massive competition in China for two stadiums, a shopping mall, and a mile long park in Hanzo, China. It is absolutely amazing to be able to work on a building that is much more freestanding—having always worked in very urban environments or working on developing cities, like I did for a client in Bogota—you know, this is something very different. It’s almost like a small, gravitational spot in the neighborhood where the park really becomes something of a green lawn for the city. And the buildings themselves were placed in very particular positions, so they really animate and generate action around themselves and kind of make the park something that you really want to go to. So it’s been an incredible project, we worked with a very amazing landscape architect, Jerry van Eyck; he’s Dutch, he used to work for West 8 and now has his own office called !melk. So as a team, we developed this project. It’s huge, so you know as we had a big team, we had amazing traffic engineering company from Italy called MIC Mobility in Chain and it was an incredible group to work with.

What’s something about Archi-Tectonics that’s unique to the culture of the firm?

Actually when we have a deadline—like for example, we just finished the design development phase for the project in China—we actually take meditation class all together at the office. And then we have a tea afterward in the living room, and then we kind of chat about how it went and how we felt about it. It’s very different than going out drinking; you know, what you used to do. I actually personally really love taking the office there and once in a while just really take a moment to stand still and thank each other and you know feel like you kind of have a moment to get your brain back and your own life back in order. And that you can just do that to me in like an hour is amazing. It’s super cute and it really is a very different way of experiencing things together. It’s a very fun way to kind of just have a moment of silence, I guess.